Barbican Cinema in London to show masterpieces of Iranian New Wave

TEHRAN – Barbican Cinema in London will host the program “Masterpieces of Iranian New Wave” from February 4 to 26, 2026.

Exploring identity and oppression with a truthfulness unmatched in any era of Iranian cinema, this program reveals a rich array of gems, many never seen in the UK, ISNA reported.

With UK premieres of newly restored films, plus a world premiere, the second exploration of Iranian New Wave film at the Barbican (following last year's sold-out program) has an extraordinary range of styles and tones, from politically weighty dramas to satirical comedies, poetic documentaries, and crime thrillers.

The program not only interrogates the boundaries between truth and fiction, but also reaches into the very heart of cinema itself. Through some of the most profound examples of self-reflexive filmmaking, it celebrates the brilliance of one of the least-known yet most remarkable cinematic new waves of the 1960s-1970s.

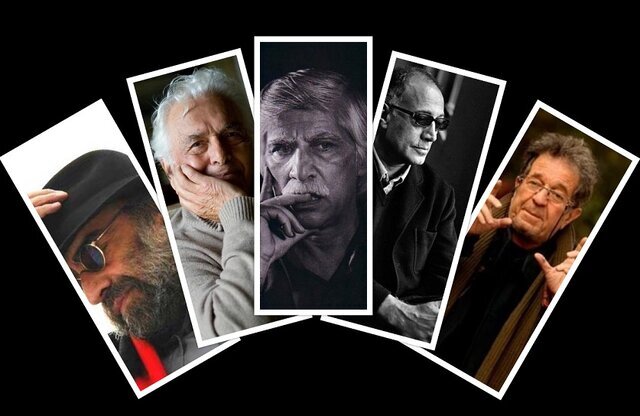

The program, presented in partnership with the Iran Heritage Foundation, features works by masters Ebrahim Golestan, Abbas Kiarostami, Bahram Beyzaie, Dariush Mehrjui, and Masoud Kimiai.

The final cinematic work of director Ebrahim Golestan, “Secrets of the Jinn Valley Treasure”, is a political satire that places the ills of a society under a comic magnifying glass.

A Monty Python–esque allegory about the corrosive impact of oil exports on Iranian life, following a villager who discovers a hidden fortune, becomes rich overnight, and swiftly transforms into a tyrant.

The film’s troubled history began even before its release. Golestan felt compelled to conceal the story during production, aware of how his intentions may be skewed. When it finally reached cinemas, the film was banned after two weeks. The questions remained – were they misinterpretations, or simply interpretations?

Golestan re-edited the film, but the director’s version was never publicly screened… until now. This screening marks the world premiere of the brand-new restoration of the film’s director’s cut.

Three classics from the golden age of the Iranian documentary movement are also included in the program.

Films by Ebrahim Golestan explore the relationship between earth, people, and the cycle of life in a uniquely poetic manner.

“A Fire,” part of his industrial documentaries (made early in his career whilst working for oil companies), was Golestan’s first major international breakthrough. It depicts the extraordinary effort to extinguish a major oilfield fire, combining dramatic immediacy with a poetic sensibility.

Golestan’s “The Hills of Marlik” appears to be about the excavation of an archaeological site, but the unearthed objects become a lens through which 3,000 years of Iranian history are seen.

“The Night It Rained” by Kamran Shirdel follows a newspaper report of a village boy who supposedly saves passengers on a train, an account that is quickly doubted and challenged. In just thirty minutes, Shirdel offers a masterful, incisive portrait of 1960s Iran.

Dariush Mehrjui’s “The Postman” presents a sharp critique of Iran’s rapid Westernization, and the tragic consequences of rash modernity clashing with unravelling tradition.

In the story, inspired by Georg Büchner’s play “Woyzeck,” Taghi (Ali Nassirian), a timid, subservient postman, lives with his wife Monir in a remote corner of northern Iran. He serves as part-time manservant to the local landowner, Niattolah. When Niattolah’s Western-educated nephew returns to remodel the dairy farm into a more profitable pig enterprise, he seduces Monir, a betrayal that hastens Taghi’s harrowing descent into madness.

Allegories are woven into satire, and while “The Postman” may be read as a testimony to class repression, it also expresses a deeper fear of all things human. The film possesses an uncanny ability to shift almost imperceptibly from symbolic satire to a metaphysical realm.

Loneliness and the experience of being orphaned, yet yearning for care and connection, lie at the heart of “Journey” and “A Wedding Suit,” two powerful films from Bahram Beyzaie and Abbas Kiarostami, respectively.

In “Journey,” two teenagers from the shantytowns of southern Tehran travel to the newly built suburbs, searching for one of the boy's parents. The journey itself transcends the boy’s personal aims. “Journey” masterfully weaves in a reflection on the history of cinema through allusions and visual citations.

“A Wedding Suit” also presents a disillusionment with the world through the eyes of young boys. The suit becomes a lens that shows the loneliness and anxieties of youth, in a society indifferent to them, where their vocational and social aspirations are stifled.

These films offer lessons in cinematic modernity from two leading figures of the Iranian New Wave, Beyzaie and Kiarostami.

A seamless fusion of myth, symbolism, folklore, and classical Persian literature, Bahram Beyzaie’s drama “The Ballad of Tara” unfolds like a feminist re-telling of Akira Kurosawa’s samurai epics.

Tara, a strong-willed widow, encounters an ancient warrior spirit in the forest near her village. The ghostly figure pursues her relentlessly, trying to steal a sword she inherited from her father. Finding himself in love with Tara, the warrior is barred from returning to the realm of the dead.

Masoud Kimiai’s cult classic “The Deer” embodies everything remarkable about Iranian cinema of the 1970s: political, provocative, sincere, furious, and tragic.

A former champion turned heroin addict reunites with a leftist classmate and finds a final, fiery form of redemption through revolutionary rage.

Premiering at the Tehran International Film Festival in November 1974, “The Deer” was banned for two years and allowed back into theaters only after Kimiai shot a new ending. Both endings will be screened at this event.

Iranian New Wave refers to a movement in Iranian cinema. It started in 1964 with Hajir Darioush's second film, “Serpent's Skin,” which was based on D.H. Lawrence's “Lady Chatterley's Lover”.

Mehrjui's two important early social documentaries, “But Problems Arose” in 1965, dealing with the cultural alienation of the Iranian youth, and “Face 75,” a critical look at the westernization of the rural culture, which was a prizewinner at the 1965 Berlin Film Festival, also contributed significantly to the establishment of the New Wave.

Later, through the works of Dariush Mehrjui, Masoud Kimiai, Nasser Taqvai, and Bahram Beyzaie, the New Wave became well established as a prominent cultural, dynamic, and intellectual trend.

Photo: From left: Masoud Kimiai, Ebrahim Golestan, Bahram Beyzaie, Abbas Kiarostami, and Dariush Mehrjui

SS/SAB

Leave a Comment