Bridging cultures: the art and impact of translation in Iran

TEHRAN-International Translation Day, celebrated annually on September 30, serves as a tribute to the art of translation and the invaluable role it plays in fostering cross-cultural communication and understanding. On this occasion, the Tehran Times explored the state of translation in Iran, which is historically known for its vast and diverse literary heritage.

Part 1

Iran has a long tradition of translating works from various languages into Persian (Farsi). This practice has been instrumental in bridging cultural gaps.

Tehran Times has interviewed three renowned translators who have made significant contributions to the translation industry in the country by rendering great works of literature, art and other subjects to Persian.

Lili Golestan, Reza Alizadeh, and Mahmoud Goudarzi are the well-known translators of different generations who have replied to five questions regarding translation. Their collective insights shed light on the challenges, successes, and evolving dynamics of translation in Iran.

First, they were asked about the characteristics of a good translation.

Answering the question, Golestan said that a translator must be proficient in both languages, especially in Persian. “They should have a good understanding of ancient texts and old poems. The most important thing for me is preserving the author's style. You cannot, for example, translate (Albert) Camus into (Leo) Tolstoy's style or shorten long sentences of (Marcel) Proust. If the style is not preserved, you've actually betrayed the trust of the reader,” she added.

“A translator must read the book they want to translate carefully several times to become familiar with its nuances. Word choice is also crucial for me. The author, their style, the era in which they lived, and the setting in which the story takes place should all be important considerations in selecting words,” she stressed.

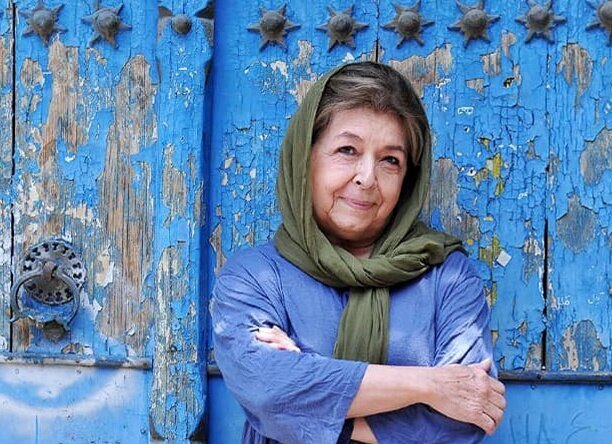

Golestan, 79, studied dress and textile design at the Decorative Art Institute of Paris and the same time attended classes on world art history and French literature at La Sorbonne.

Lili Golestan

“Nothing, and So Be It” by Oriana Fallaci was her first translation, which was published in 1967. The book was received well and encouraged her to translate more novels. She has since translated more than 30 books including “Chronicle of a Death Foretold,” and “The Fragrance of Guava,” by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, “Six Memos for the Next Millennium,” and “If on a Winter's Night a Traveler,” by Italo Calvino, “Remarks on Color,” by Ludwig Wittgenstein, “Story Number 3,” by Eugène Ionesco, “Life with Picasso,” by Françoise Gilot, and “Tistou of the Green Thumbs,” by Maurice Druon.

In response to the same question, Alizadeh said that his opinion about the qualities of a good translation had changed over time. “I used to think that fidelity to the original text should be very mechanical, for example, a word-for-word translation, or at most a sentence-for-sentence one was the best. But gradually, I realized that it was not really so and there were excellent translations that didn't fit into this framework,” he noted.

“What used to be considered a correct translation was when you translated a sentence literally and then added a note saying, 'Dear reader, if you didn't get what it meant, that’s because this sentence in English is an idiomatic expression similar to a proverb in Persian’ and then included the Persian equivalent. But now it seems to me that the translator must have some flexibility, and you can't be so strict,” Alizadeh explained.

“In the past, one of the criteria for translation was to evoke the same emotions in the reader of the target language as the original text did in the reader of the source language. But this is really hard to measure, and it seems to me that a translator succeeds in their work only if the reader of the target language enjoys reading the translated text. For example, Houshang Pirnazar's translation of ‘Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ (by Mark Twain) had this quality and conveyed a good feeling,” he elaborated.

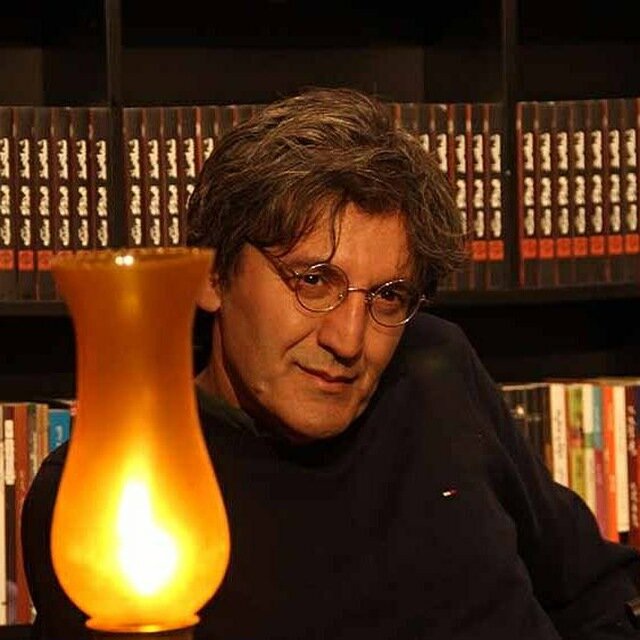

Alizadeh, 59, is another accomplished Iranian translator known for his contributions to the world of literature and translation.

Reza Alizadeh

His first work of translation was Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Birthmark,” which was published in 1991. Since then, he has translated over 30 books.

Basically, he is famous for rendering works of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien, the author of high fantasy works such as “The Lord of the Rings” and “The Hobbit,” into Persian.

He has also brought the works of Umberto Eco to Iranian readers, demonstrating his versatility in translating diverse literary styles.

Alizadeh's translations have played a crucial role in introducing international literature to Persian-speaking audiences, contributing to cultural enrichment.

Goudarzi, for his part, said that a good translation should convey not only the meaning but also the style, the register of the language, and in a word, the soul of the text.

“When reading a translated book, readers should not notice the translator's work. The quality of the translation should be such that they have the feeling of reading the author's original text,” he stated.

Goudarzi, 46, is a graduate of French language and literature. He started his career as a translator in 2006 by translating short stories by Emile Zola for magazines and has since published about 60 books.

Mahmoud Goudarzi

His works include translation of various authors such as Bram Stoker's “Dracula,” Jack London’s “Scarlet Plague,” "Guy de Maupassant’s “Our Heart,” Voltaire's “Candide,” Henry James’ “Daisy Miller,” and Alexandre Dumas’ “Gabriel Lambert”.

While the new generation of translators may not have the same level of experience as veterans, they can excel by being attuned to contemporary language use and cultural shifts

New generation of translators

The next two questions asked respondents about the translation situation in Iran and the position of the new generation of translators compared to experienced and veteran translators.

“We now have very good young educated translators with a proper understanding of Persian,” Golestan said. “I believe that if a book is published with a bad translation, the publisher is at fault for not recognizing the poor quality of the translation. The translator bears less blame”.

Recalling what had happened to her in this regard, she said, “A young girl called and said she had heard that I had many important books in French. ‘Can I take one of your books and translate it?’ she asked. I then asked her where she learned French. ‘I just signed up for a language course last week,’ she replied! So even if a translation is of poor quality, publishers should not accept it”.

Regarding the different generations of translators, she said: “Comparing today's translators to the past, we should not expect to have many great figures like Mohammad Ghazi, Abdullah Tavakkol, or Reza Seyed-Hosseini, but we do have very good translators with excellent taste in book selection”.

Alizadeh believes that translation in Iran has had its ups and downs, but overall, it can be said that it has progressed over, becoming more precise, and with better equivalences established.

“However, one issue is the lack of a cohesive and continuous system of translation criticism. Having such a system could further enhance the quality of translations. If there were a structured critique of translations, the new generation could also benefit from it in terms of their own progress and development,” he said.

On the status of the new generation of translators, Alizadeh believes that they are generally good. “If there is a problem, it is with their detailed knowledge of Persian language,” he stated.

Goudarzi hopes that there will be always a few who will keep the fire burning. “It survives but I'm not sure if it progresses or prospers. I guess we are publishing fewer literary works nowadays, and self-help books, thrillers, and such have occupied more space in the publishing business. Therefore, if we want to assess the quality, we must take those few literary works into consideration,” he noted.

“As for the financial situation, it has seen better days. The urge to make money or more of it, makes publishing houses interested in what the majority wants. So, the literary quality is not a priority anymore,” Goudarzi rued.

Speaking about the young translators, he said: “I don't know all the new translators. But as far as I know, they are better equipped, and thanks to technology they have better access to references. However, they are not as well-read or meticulous as the older generation of translators, and their knowledge of Farsi language is not adequate”.

Considering what the three well-known translators said, it can be concluded that the new generation of translators often bring fresh perspectives and linguistic skills to the field. While they may not have the same level of experience as veterans, they can excel by being attuned to contemporary language use and cultural shifts.

SS/SAB

Leave a Comment