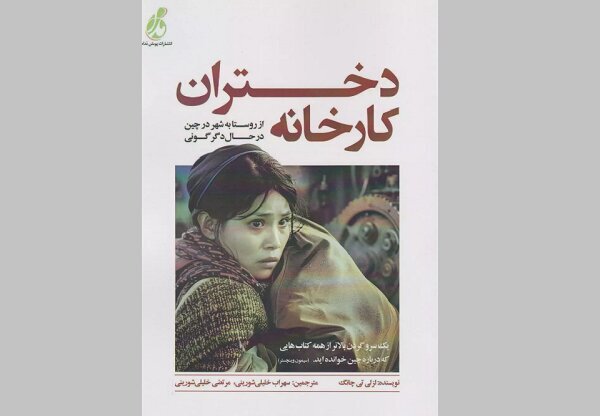

Leslie Chang’s “Factory Girls” available in Persian

TEHRAN-The Persian translation of the book “Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China” written by Leslie T. Chang has been released in bookstores across Iran.

Translated by Sohrab Khalili Shourini and Morteza Khalili Shourini, the book has been published by Pouyesh Modam Publications, Mehr reported.

An eye-opening and previously untold story, “Factory Girls” is the first look into the everyday lives of the migrant factory population in China.

China has 130 million migrant workers—the largest migration in human history. In “Factory Girls,” Leslie T. Chang, a former correspondent for the Wall Street Journal in Beijing, tells the story of these workers primarily through the lives of two young women, whom she follows over the course of three years as they attempt to rise from the assembly lines of Dongguan, an industrial city in China’s Pearl River Delta. As she tracks their lives, Chang paints a never-before-seen picture of migrant life—a world where nearly everyone is under thirty; where you can lose your boyfriend and your friends with the loss of a mobile phone; where a few computer or English lessons can catapult you into a completely different social class.

Chang takes the readers inside a sneaker factory so large that it has its own hospital, movie theater, and fire department; to posh karaoke bars that are fronts for prostitution; to makeshift English classes where students shave their heads in monk-like devotion and sit day after day in front of machines watching English words flash by; and back to a farming village for the Chinese New Year, revealing the poverty and idleness of rural life that drive young girls to leave home in the first place.

Throughout this riveting portrait, Chang also interweaves the story of her own family’s migrations, within China and to the West, providing historical and personal frames of reference for her investigation.

A book of global significance that provides new insight into China, “Factory Girls” demonstrates how the mass movement from rural villages to cities is remaking individual lives and transforming Chinese society, much as immigration to America’s shores remade that country a century ago.

Leslie Chang is an American writer who digs deeply into her Chinese heritage. In “Factory Girls,” the setting is the greatest migration in human history of more than 130 million people within the last three decades. Younger country people move from rural to urban-industrial China to seek a better livelihood for themselves and, through money sent home, for their loved ones left behind. These migrants represent the apparent inexhaustible supply of cheap labor that China needs for building its sprawling cities with their high-rises and factory complexes. They maintain and clean its buildings and offices, attend to the households and children of the rising urban middle class, and fill and replenish the assembly lines and various receiving and shipping departments of China’s burgeoning factories.

Chang’s focus is on the township of Dongguan. Seventy percent of Dongguan’s population are women who work in its thousands of factories churning out textiles, electronics, shoes, appliances, toys, and Christmas decorations and lights.

Dongguan is a natural place for Chang to contact and get to know her factory girls. Through dogged determination and persistence, Chang is able to make sustained contact and put a human face on people with actual names to an otherwise impersonal monolith of China’s migrant workers and floating population. They are vibrant personalities with interesting stories to tell.

These girls are largely poorly educated youth, ages 16 to 25 years, who begin their first industrial employment by joining an army of assembly line workers. The very moment they are employed on the line, they are already thinking of ways to free themselves from their monotonous and fatiguing tasks. Besides being lured to the city by the possibility of improving the family economy and the excitement of seeing the world, these girls are also driven by the boredom and idleness of the hum-drum farm life that their parents and younger siblings easily manage.

Being young and steeped in the Chinese tradition of self-cultivation (however much on the unconscious level) and despite inadequate formal education, they do often ask the fundamental question of what life is all about. They are anxious to seek opportunities, learning computer skills, speaking English, gaining poise and self-confidence in assertive training—all to remake themselves into more marketable human resources in the plethora of self-improvement schools that have mushroomed in their factory city.

SS/SAB

Leave a Comment