Commemoration of unjust incarceration of Japanese Americans

TEHRAN – 81 years ago, the U.S. president issued an executive order ordering more than 100,000 Japanese who were considered a threat to the country's national security to be detained and sent to internment camps.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese on December 7, 1941, suspicion fell on Japanese American communities in the western United States. The U.S. Department of the Treasury froze the assets of all citizens and resident aliens who were born in Japan and the Department of Justice arrested some 1,500 religious and community leaders as potentially dangerous enemy aliens.

Because a large percentage of the Japanese American citizens were in close proximity to vital war assets along the Pacific coast, U.S. military commanders petitioned Secretary of War Henry Stimson to intervene. The result was Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066.

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which led to the forced relocation of approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. While 9066 also affected Italian and German Americans, the largest numbers of detainees were by far Japanese Americans.

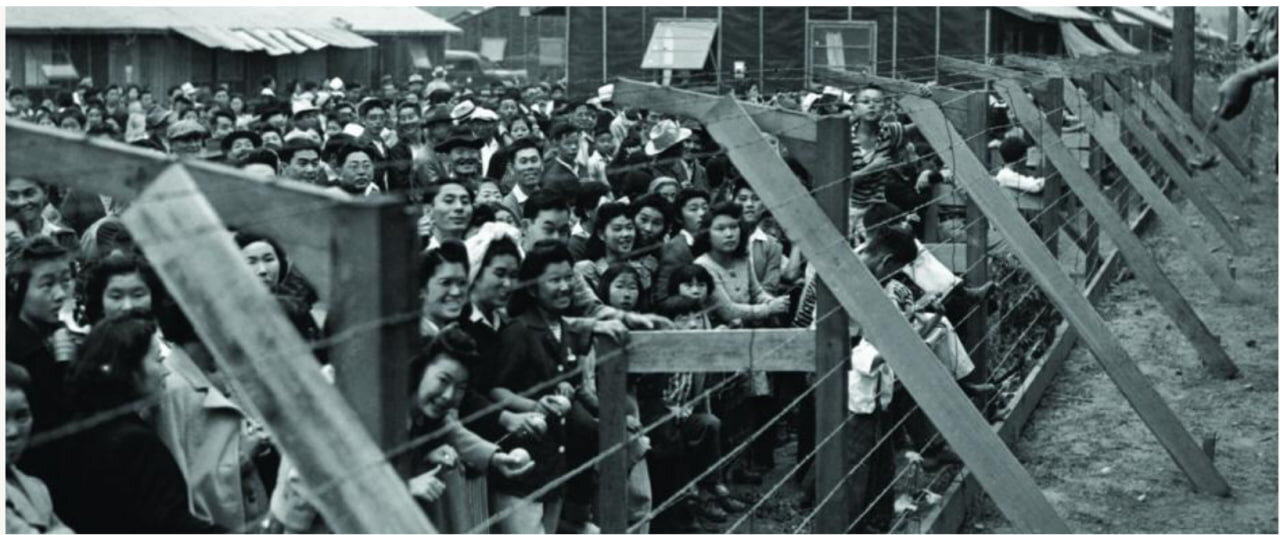

There were 10 camps set up nationally, and about 120,000 people were interned in the camps during the war. More than two-thirds of these people were native born American citizens. They were confined in inland internment camps operated by the military. They abruptly forced to abandon or sell their homes and businesses, many lost everything they owned.

Japanese immigrants and their descendants, regardless of American citizenship status or length of residence, were systematically rounded up and placed in prison camps. Evacuees, as they were sometimes called, could take only as many possessions as they could carry and were forcibly placed in crude, cramped quarters.

The evacuees were taken first to temporary assembly centers, requisitioned fairgrounds and horse racing tracks where living quarters were often converted livestock stalls. As construction on the more permanent and isolated War Relocation Authority camps was completed, the population was transferred by truck or train.

These accommodations consisted of tar paper-walled frame buildings in parts of the country with bitter winters and often hot summers. The camps were guarded by armed soldiers and fenced with barbed wire. Camps held up to 18,000 people, and were small cities, with medical care, food, and education provided by the government. Adults were offered camp jobs with wages of $12 to $19 per month, and many camp services such as medical care and education were provided by the camp inmates themselves.

In December 1944, Roosevelt suspended Executive Order 9066, forced to do so by the Supreme Court decision Ex parte Endo. Detainees were released, often to resettlement facilities and temporary housing, and the camps were shut down by 1946.

In the years after the war, the interned Japanese Americans had to rebuild their lives but had lost a lot. American citizens and long-time residents who had been incarcerated lost their personal liberties; many also lost their homes, businesses, property, and savings.

Individuals born in Japan were not allowed to become naturalized US citizens until after passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952.

In subsequent years, the American internment policy has been met with harsh criticism. On February 19, 1976, President Gerald Ford signed a proclamation formally terminating Executive Order 9066.

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan issued a public apology on behalf of the government and authorized reparations for former Japanese American internees or their descendants. US Congress awarded restitution payments of $20,000 to each survivor of the 10 camps.

Leave a Comment