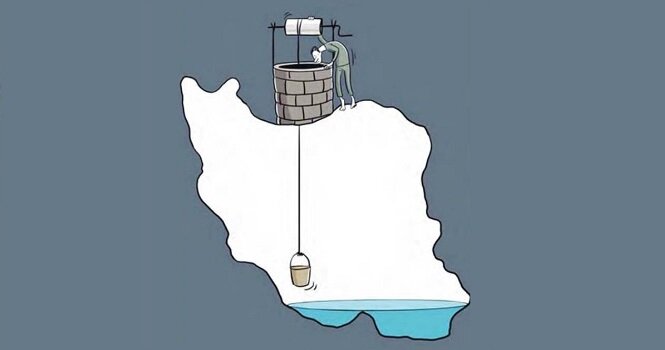

Quenching thirst of arid plains or jeopardizing nature?

TEHRAN – Transferring water from a basin to drought-ridden areas over varying distances is among the plans in Iran to quench the thirst of some provinces, while construction of such tunnels is inherently risky and can result in unpredicted events or irreparable environmental issue.

Water resources are deemed essential for agricultural, industrial, and urban development, especially in developing countries, and water scarcity can put severe pressure on the economy, society, and culture.

To reach prevent problems caused by water shortages, transferring the water from coastal to central areas is a part of Iran’s strategy for water supply, given that vast swathes of the country are regarded as arid and semiarid.

The construction and operation of water transfer tunnels to different parts of the country have always been accompanied by criticism.

Hossein Rafi’e, a water activist, said that the worst kind of water transfer is through canals and pipelines, adding that such measures would lead to many environmental challenges that would be very difficult or almost impossible to compensate.

Nature is in order, and the transfer of water is an interference in this natural order, and human beings, in order to meet their water needs, take advantage of nature and water resources without caring about the environment, he lamented.

He went on to note that rivers naturally irrigate their surroundings and supply aquifers along their way, so the transfer of water through covered pipes can cause serious environmental damage.

Referring to the water transfer project from Karaj Dam to Tehran, which started in 2005, he explained that the project will leave no significant amount of water in the Karaj River, and all gardens, vegetation, and the surrounding environment will be degraded.

Also, the water required for groundwater resources will no longer be provided, so that there will be a big challenge causing dire consequences or high cost to compensate for, but considering today’s need and ignoring the future, is the worst kind of water management, he stated.

Rafi’e emphasizing that the Iranians have taken very clever steps to transfer water in the past noted that “In the past, the Iranians used to transfer water through Qantas and in a natural way, harnessing water along the route where necessary.”

Qanats had extraordinary features, but unfortunately, now we do not use this indigenous-traditional knowledge and instead use new methods that have not been localized, he concluded.

Water transfer projects

A project on transferring water from Zab River to the lake has been proposed by the government and a budget of 3 trillion rials (nearly $71 million at the official rate of 42,000 rials) has been earmarked in this regard.

The Zab water transfer tunnel to Lake Urmia will be completed in the next few months, and with its operation, the lake's water volume will reach 14.7 billion cubic meters over the next seven years and will rehabilitate the lake after years.

A water transfer project has been proposed by the government which looked to Oman seawater quenching the thirst of the southeastern province of Sistan-Baluchestan, as well as the eastern provinces of South Khorasan and Khorasan Razavi. A budget of $400 million was allocated by the government in March 2016.

The project aims to boost production, industry, and agriculture, as well as provide potable water to residents in arid areas.

Another water transfer project from the Persian Gulf to the provinces of Kerman, Yazd, and Hormozgan will be put into operation in the next Iranian calendar month of Mehr (September 23-October 22).

The water transfer project from the Persian Gulf is being implemented on a large scale with 11 pumping stations to be established over 830 kilometers of land, which is a unique project in the country.

No solution: water transfer entails an economic, environmental burden

Experts believe that these projects entailing economic and environmental burden are no solution to droughts, and demanded the water transfer projects to be dismissed due to the irreparable damages to the environment namely deforestation, wildlife habitat destruction, biodiversity degradation, improper land change use, and contaminated seawater.

Mehdi Zare, a seismic expert, said that human intervention, speeding up climate change, is one of the major threats to today’s human life and even the future. One of the threats is that transferring water to dry areas increases the population burden in those areas while imposing unsustainable development where there is no suitable climate for such a concentration.

The disastrous consequences of such interventions have so far been appeared in the country, especially in provinces of Tehran and Isfahan located in arid areas, which have been demolished being accommodated a population of three to five times the size of their carrying capacity in the last 50 years, he lamented.

Additionally, the development of huge industries inappropriately deployed to their climatic conditions added insult to injury, he added.

What is wrong with qanats?

Some experts believe that the current water scarcity is due to poor water management policies, do qanats give us the right policy? What was wrong with these traditional water supply systems that have been put aside?

Over the centuries, qanats have served as the main supplier of freshwater in arid regions of Iran, as provided the opportunity for people to live in extremely dry zones (even in deserts), and thus helped harmonize the population distribution across the country.

The ancient qanat system of tapping alluvial aquifers at the heads of valleys and conducting the water along underground tunnels by gravity, often over many kilometers, first appeared in Iran, which was then spread to other Middle Eastern countries, China, India, Japan, North Africa, Spain and from there to Latin America.

Employing this ancient water supply system may reveal and highlight some benefits to contain water shortage in the country.

Throughout the arid regions of Iran, agricultural and permanent settlements are supported by subsurface water or freshwater resources withdrawal, while qanats representing the system include rest areas for workers, water reservoirs, and watermills.

According to the Ministry of Energy, about 36,300 qanats have been identified in Iran, which has been saturated with water for over 2,000 years.

Qanats can come efficient to contain water scarcity due to relatively low cost, low evaporation rates, and not requiring technical knowledge, moreover, they proved sustainable being used in perpetuity without posing any damages to the environment, despite new water transfer projects, which not only puts the environment in danger but brings the country heavy economic burden.

FB/MG

Leave a Comment