Traces of large-scale Sasanian agricultural estate discovered in southern Iran

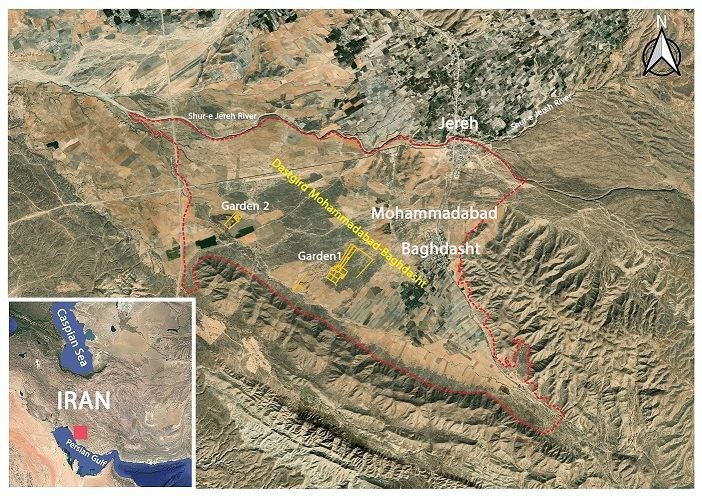

TEHRAN - A significant Sasanian agricultural estate, or dastgerd, featuring multiple gardens and kushks, has been identified in Mohammadabad-Baghdasht Plain, situated in Fars province, southern Iran.

The discovery was made through the integration of remote sensing data from ancient aerial photographs, satellite imagery, and intensive field surveys.

According to Dr. Parsa Ghasemi, a Ph.D. in Archaeology from Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne University and an expert in landscape archaeology, the estate was first noted during field surveys in 2005. Over the past decade, ongoing documentation has revealed that the estate spans nearly 37 square kilometers, making it one of the largest agricultural estates from the Sasanian period (224–651 CE) in the Pars region.

The estate originally included two large gardens, three kushks (palaces), and numerous other structures, all designed to support large-scale agriculture and water management. Water for the estate was sourced from the kariz (qanat) system, the Shur-e Jereh River, and seasonal rainwater. The estate stretches across almost the entire Mohammadabad-Baghdasht Plain, extending from the Mansourabad Pass in the east to the Shur-e Jereh River in the west.

Ghasemi pointed out that the Nargeszar-e Jereh, a popular tourist attraction in the region, is also part of this vast agricultural estate. Archaeological evidence suggests that this area was cultivated during the Sasanian era, and the estate continued to be utilized well into the Timurid period (1370–1507 CE). A recently uncovered endowment document indicates that, during the reign of Shahrokh Timurid, a farm named Nasirabad was situated within the estate and its income was donated to the Khan School in Shiraz. This suggests that the estate’s agricultural use persisted long after the fall of the Sasanian Empire.

The estate’s extensive water management systems, including over 134 stone clearance mounds ranging from 2 to 4 meters high, showcase the sophisticated infrastructure of the Sasanian agricultural program. These mounds were created by collecting stones from the plain, and they played a crucial role in enhancing the agricultural productivity of the region.

In addition to the Mohammadabad-Baghdasht discovery, Ghasemi’s research has led to the identification of other significant Sasanian garden complexes, including the royal gardens at Bozpar in Dashtestan, Bushehr province, previously only known for their associated palaces, such as Kushk-e Ardeshir and Zendan-e Soleiman.

The research significantly sheds new light on large-scale agriculture in the Pars region, particularly during the Sasanian period, and reveals the lasting impact of these agricultural estates into the post-Sasanian eras. These large, cultivated landscapes, often described as earthly paradises, were integral not only for agricultural production but also served as centers of leisure, hospitality, and regional economic development.

Unfortunately, many of these ancient gardens have been severely damaged over time due to intensive modern agricultural activities.

Ghasemi hopes that this research will draw attention to the urgent need for conservation efforts by authorities, particularly the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, to preserve these valuable historical sites before they are lost entirely.

AM