Excavations shed new light on Isfahan’s ancient craftsmanship and trade

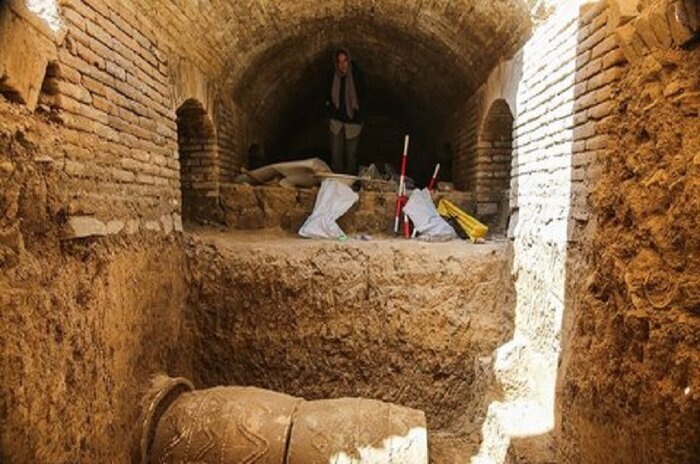

TEHRAN – Archaeological digs conducted on accidentally-discovered ruins in Isfahan have revealed hidden layers of ancient craftsmanship and trade in the renowned Iranian city which was once the capital of Persia in the Safavid era.

In a recent interview with ISNA, archaeologist Ali Shojai Isfahani, who led the excavations, elaborated on the findings: “Our studies, conducted in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Art, reveal that this site was once a major marketplace for production and distribution, with origins predating the Safavid and even Mongol eras. Various sections dedicated to the production of pottery, glass, metal, and decorative items were active here.”

So far, two archaeological seasons have been completed and the third has just commenced on the ruins, located at Kamar-Zarrin Pasagway adjacent to the UNESCO-registered Jameh Mosque of Isfahan.

Over two excavation seasons, the team has unearthed significant evidence spanning various historical periods, indicating the passageway’s long-standing importance in the heart of Isfahan’s historical fabric.

According to Shojai Isfahani, the initial excavations have yielded architectural remnants and movable artifacts from diverse Islamic periods, dating from the 9th and 10th centuries to the Qajar and early Pahlavi eras. “These discoveries have confirmed the long-held belief that this passageway was a bustling production and trade hub.”

The presence of raw materials, finished products, and production waste all point to a lively production environment in the heart of Isfahan, near the Jameh Mosque, which dates back to the same period. The current findings are particularly significant given Isfahan’s continued reputation as a city of craftsmanship, highlighting the historical continuity of artisanal production.

Notably, the intact architectural remains present a unique opportunity for preservation and public display. Plans are underway to develop a preservation and display strategy in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Art and other experts.

Breaking with traditional archaeological practices, the team allowed public access to the site, even permitting photography. This openness not only engaged the public but also helped raise public awareness of preserving cultural heritage.

Shojai Isfahani said that his team provided opportunities for interested people to observe the excavation scene in a controlled way. He emphasized the dual objectives behind their approach to the excavations. First, they aimed to raise public awareness and sensitivity toward the passageway. Second, they sought to demystify the process of archaeological studies for the public, dispelling the common misconception that archaeologists may be treasure hunters.

Shojai Isfahani underscored the responsibility of scholars and locals alike to preserve and study these artifacts, which testify to Isfahan’s magnificent past. “The excavations at Kamar-Zarrin have demonstrated that beneath the modern layers of Isfahan, there lies a wealth of historical evidence. “

Furthermore, archaeologist Aqil Aqili provided additional context to ISNA, highlighting the likelihood of extensive historical layers in Isfahan, particularly given the city’s geographic centrality and the presence of the Zayandeh-Rud River. He speculated that significant pre-Islamic artifacts might be buried beneath layers of alluvial deposits and mud, underscoring the importance of continued excavations.

Aqili stressed that ongoing archaeological work is crucial to unearthing the region’s rich history and cultural identity.

Isfahan, once the nucleus of international trade and diplomacy in Iran, stands today as one of Iran’s premier tourist destinations for compelling reasons.

In 1587, Shah Abbas the Great ascended to rule over Persia’s Safavid dynasty and handpicked Isfahan as the pinnacle of his reign, endeavoring to surpass all other cities. His era witnessed an unparalleled transformation, marked by the construction of an impressive array of palaces, mosques, gardens, and bridges.

Subsequent rulers under Shah Abbas continued the city’s embellishment. Isfahan, then inhabited by 600,000 people, boasted an astounding 162 mosques, 48 colleges, 273 public baths, and an impressive count of 1,802 caravanserais—sprawling courtyards flanked by structures, serving as medieval hubs offering respite for travelers, their camels, and accommodations.

The city’s allure lies in its plethora of architectural marvels—unrivaled Islamic structures, vibrant bazaars, museums, Persian gardens, and tree-lined avenues. Isfahan beckons explorers to wander its labyrinthine bazaars, luxuriate in its serene gardens, and engage with its warm-hearted populace. Notably, it is revered not only for its wealth of historical bridges but also for the life-sustaining Zayandeh Rud River, a source of original beauty and fertility for the city.

The expansive Imam Square, renowned as Naghsh-e Jahan Square (meaning “Image of the World”), stands as one of the world’s largest squares (500m by 160m) and an exquisite embodiment of urban design. Erected in the early 17th century, this UNESCO-recognized square hosts Isfahan’s most captivating landmarks.

Such a warm development led to the creation of a motto: “Isfahan nesfe Jahan”— “Isfahan is half the world.” This poetic adage alludes to the belief that witnessing Isfahan equates to experiencing half the globe.

AM