Archaeological-rich Zel Cave to undergo excavation

TEHRAN – Zel Cave, an archaeological-rich place in central Iran, will undergo a 2nd authorized season of excavation in the near future.

Over the past century, this cave has been looted several times by unauthorized excavators, and many of its Pahlavi-scripted leather inscriptions have been plundered, with a substantial number held in American and German universities and private collections.

Situated near the village of Hastijan in Delijan county of Markazi province, the cave underwent an extensive excavation last year, yielding relics ranging from a Sasanian-era reed flute to one-centimeter bags, sleeves, and pieces of personal ornamentation.

Paying a visit to the cave on Sunday, Mahmoud Moradi, the provincial tourism chief, underlined discoveries made in the first archaeological season as “significant”.

“Among the finds were raw bricks, pottery shards, textile fragments, and leather inscriptions dating back to the Sassanid era,” the official said.

Azar (November-December) last year, in the presence of the acting head of the archaeological team, experts, and archaeological supervisors.

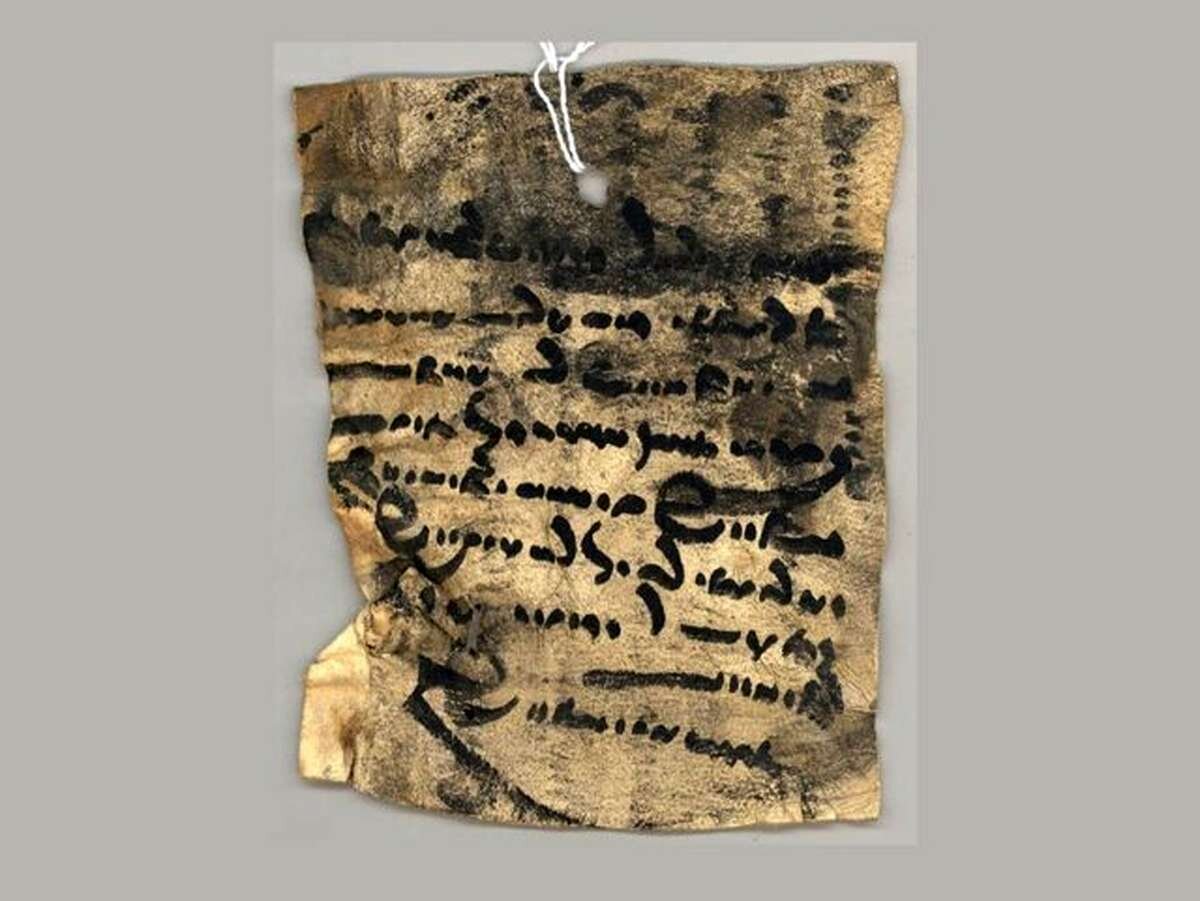

Further detailing the discoveries, Moradi highlighted, "The leather inscriptions, inscribed in Pahlavi script, belong to the Sassanid period and were uncovered during the first season of archaeological exploration at Zel Cave.

The excavation will continue until the end of summer, the official said.

Zel Cave, also known as Takht-e Qaleh, is nestled within the rugged terrain south of Takht-e Qaleh Mountain, approximately 14 kilometers southeast of Delijan and 2.5 kilometers northeast of Hastijan village.

Regrettably, the integrity of the cave's architectural features has been compromised by unauthorized excavations. Throughout the past century, Zel Cave has fallen victim to numerous instances of looting by unauthorized individuals, resulting in the plundering of many of its leather inscriptions scripted in Pahlavi. A considerable portion of these inscriptions now resides in collections housed within American and German universities, as well as private collections. Remarkably, despite a hiatus of seven decades, archaeological exploration of the cave resumed in October and November of the current year, shedding light on its tumultuous history.

Archaeological findings from this recent excavation effort include leather fabrics bearing inscriptions, wooden implements, fragments of pottery, and remnants of animal bones, all dating back to the late Sasanian and early Islamic periods. This resurgence of exploration promises to unveil further insights into the cave's past, despite the setbacks inflicted by illicit excavations in decades past.

A part of a sleeve without an owner!

Sections of a garment's sleeves, its owner's whereabouts, and their fate remaining unknown, are preserved amid the cave's stones and dry space. These sleeve ends are now showcased in museum display cases along with a part of a shoe lacking its sole.

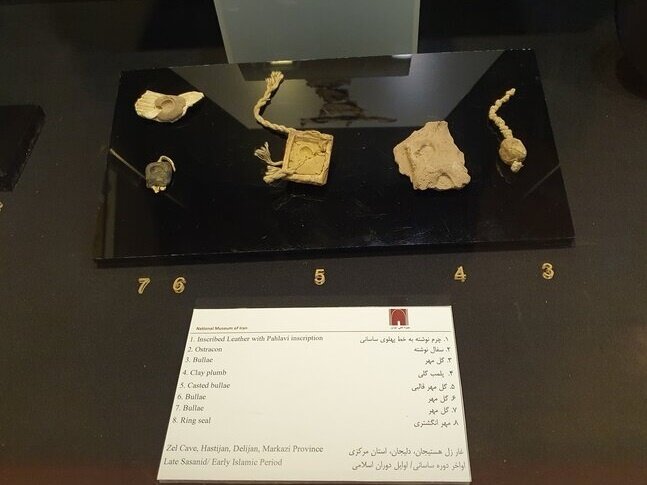

Other leather inscriptions from the late Sasanian and early Islamic periods have been found but remain unread. Now, some of these fabrics, leather inscriptions, and ropes made from goat hair are exhibited in the halls of the National Museum of Iran

The magic of a reed flute

One of the findings pertains to a reed flute, remarkably similar in shape and composition to modern-day flutes. This flute indicates that Iran had written materials from the Sasanian era using this instrument. Archaeologists believe that this discovery has pushed back the history of reed-writing instruments by 1,400 years.

Inscribed pottery, a seal in the form of a rose, a ring seal, clay seals, part of a wicker basket, wooden tools, and combs, and a necklace alongside the fabrics from that period constitute another section of the Hastijan’s cave exhibition.

A letter from brother to sister

One of the most significant findings from this cave is related to a document written by a brother to his sister. This document, which is being kept at the Bancroft Library in Berkeley, California, demonstrates the importance placed on honoring women's status during the Sasanian period and afterward. The content of this letter has attracted considerable attention from archaeologists, researchers, linguists, experts, and even visitors.

This private letter dates back to the late Sasanian era or the beginning of the Islamic period and was probably written somewhere between Qom and Kashan. It indicates widespread literacy and writing among the Iranian populace before the advent of Islam.

In the document, it is written: May the pearls of my dear sister, whom God may make happier, bring every happiness to my sister. I, through the hand of fate, have sent a bottle of pure oil. Write to me about your health and well-being, and be reassured about my 'well-being' and my children.

However, the last line of this leather inscription, ‘Send the oil soon,’ remains a matter of dispute among archaeologists. Some claim this sentence exists in the leather inscription, while others refute its presence.

AM