Interview: expert explores women’s role in Persian carpet weaving

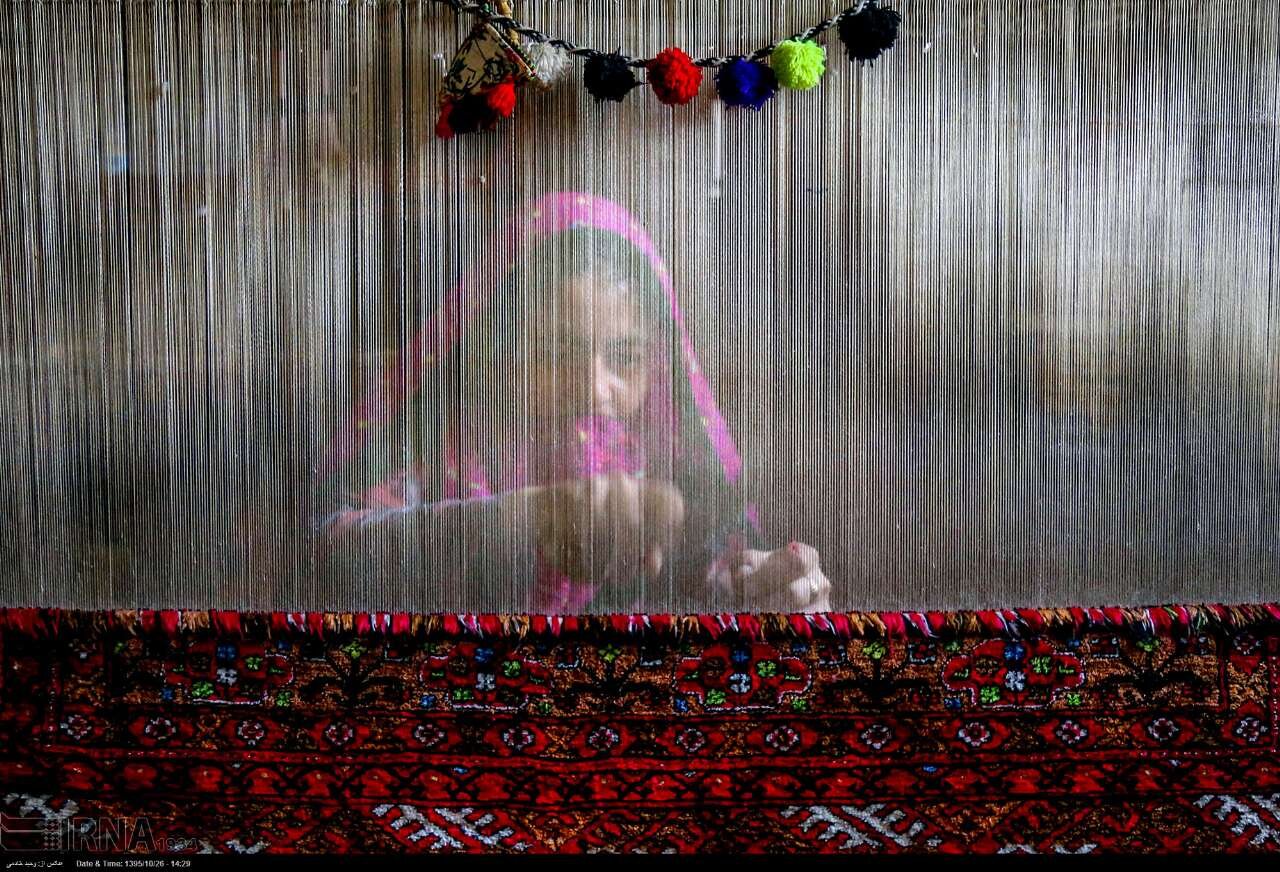

ISFAHAN – The art of carpet weaving has been an integral part of Iranian culture and tradition with many women as its silent heroes for centuries.

From the humble villages to the bustling city centers, their skillful hands have meticulously crafted more decorative pieces, carrying forth the legacy of carpet weaving across generations to preserve that top cultural heritage.

However, it seems that their pivotal role in that intricate craft is often overlooked. In an exclusive interview with Mahshad Abzari, a carpet expert, delves into the historical significance and profound impact of women in shaping the narrative of this artistry that has not only adorned floors but woven tales of heritage and identity.

In this conversation, the expert shares with us the historical significance of women in the evolution of this ancient art form, the challenges they face today, and the essential role of education and governmental support in preserving this invaluable heritage.

What’s your definition of a Persian carpet as someone who has been involved in carpet design for years?

Carpets in Iran are an inseparable part of people’s daily lives. We coexist with carpets in various ways – resting on them, walking over them, and aesthetically, they contribute significantly to the beauty of our homes.

Carpets not only represent the deep history, art, and social life of our nation but have been an element embedded in Iran’s culture since ancient times. Interestingly, most of its creators in bygone eras were women.

Abzari said that in addition to their aesthetic delights, Persian rugs are somehow a cultural medium. For instance, if you were to ask audiences outside the country about examples of Iranian art, Persian carpet may be the first.

What else about women’s roles?

In the far past, women were responsible for all the stages of carpet production, from procuring raw materials to designing and mentally crafting them. The mental designs, reflecting their aspirations, desire, and beliefs, were transmitted from mother to daughter in the form of symbolic patterns. These patterns were based on the culture and lifestyle of these women.

So, why are women seen behind weaving looms?

This trend persisted for centuries until the Qajar era [1789-1925] when the carpet export and trade sector thrived, shifting focus from the weavers’ taste and mindset to the preferences of mainly European buyers. Consequently, the value of women, as the primary creators of carpets, diminished, and their role became confined, primarily, to weaving.

Especially during the onset of multinational corporations investing in Iran, this situation limited women’s roles to mere weavers, causing significant harm, as documented in Western travelogues. For instance, a report in the [then] British consulate in Kerman by a female physician, one of the founders of the city’s first hospital, highlighted that a considerable portion of women’s deaths during childbirth was due to the physical toll of sitting and weaving carpets since childhood.

This continued into the early Pahlavi era when labor protection laws were introduced, mainly focusing on male workers in factories, neglecting the women who shouldered the significant burden of carpet production.

What are existing prospects?

Despite recent advancements in universities and higher education centers significantly advancing the industry, young women entering these domains such as weaving, design, and restoration are evident. However, a major portion of this profitable trade in investment, marketing, and sales remains predominantly in the hands of men. Consequently, gender challenges persist in legitimizing women in this field.

Any prompt solution?

In the realms of marketing and exhibitions, women are still not acknowledged as primary figures. Consequently, it is noticeable that only men are visible in this field at exhibitions and conferences.

These women, despite all the difficulties and challenges, are still recognized as the primary pillars of this industry. However, for their promotion, there is a need to develop education, dialogue, technical skills, active participation in global markets, and create more educational opportunities.

What is your suggestion for the continuation of this ancient art among newer generations?

Above all, I believe education plays a pivotal role in the current era. Traditional face-to-face methods or specialized workshops are no longer enough for training new generations of carpet designers and weavers.

Accordingly, a comprehensive approach to innovative teaching methods, understanding tools, and different markets is necessary to generate more interest in this extraordinary art form among the new generation.

However, regrettably, in higher educational institutions, there is still an emphasis on traditional methods that negatively impact students in this field.

Such educational efforts are expected to reach their maximum potential when the community of carpet weavers feels the protective umbrella of government and relevant institutions.

Glimpses of Persian carpet

Persian carpets are sought after internationally, with patterns of Persian garden being arguably the most characteristic feature of them all. Weavers spend several months in front of a loom, stringing and knotting thousands of threads. Some practice established patterns. Some make their own.

Each Persian carpet is a scene that seems ageless, a procedure that can take as long as a year. These efforts have long put Iran’s carpets among the most complex and labor-intensive handicrafts in the world. When the weaving is finally done, the carpet is cut, washed, and put out in the sun to dry.

Throughout history, invaders, politicians, and even enemies have left their impact on Iran’s carpets. As mentioned by the Britannica Encyclopedia, little is known about Persian carpet-making before the 15th century, when art was already approaching a peak.

AFM