Qanat: ancient marvel for water access, air conditioning and refrigeration

TEHRAN - With roots tracing back over 3,000 years, the qanat stands as an astounding engineering feat that ancient Iranians used as an enduring solution to easily obtainable water.

Qanat emerged as a testament to ancient Iranians’ ingenuity in a land where securing pure water within an arid and harsh landscape seemed almost impossible.

The qanat, referred to as Kariz in Persian and recognized by its Arabic name, this ingenious system also served as an eco-friendly method for air conditioning and refrigeration.

Subterranean mastery

Essentially, a qanat functions as an underground conduit, transporting fresh water from elevated mountain sources to lower-altitude openings for irrigation—an ideal solution in regions blessed with abundant mountainous terrain.

The construction process involves excavating a shaft akin to an anthill underground until it reaches the water source. While some shafts necessitate minimal digging, others extend up to 300 meters beneath the surface. Additional shafts, resembling anthills, are periodically bored to extract soil and ensure adequate ventilation for workers excavating the subterranean passages. Precision is paramount in determining the qanat’s slope: too steep risks erosion due to the water’s force, while being too flat impedes water flow.

Nevertheless, the complexity of this system yields significant rewards. For millennia, these clandestine aqueducts have empowered Iranians to access and distribute water across some of the most arid terrains.

Beyond water supply

The qanat’s utility extends beyond providing potable water; in locales like Yazd in central Iran, it collaborates with a badgir (an Iranian wind-catcher) to mitigate indoor temperatures. Water within the qanat cools incoming warm air entering through a shaft, subsequently released into basements and expelled through the badgir’s upper openings. This ancient method of air conditioning remains integral to Yazd’s engineering and architectural landscape.

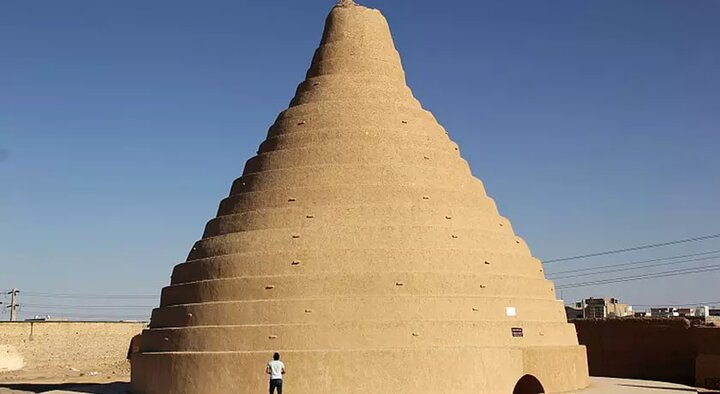

Moreover, the qanat enabled the storage of substantial quantities of ice in desert climes. Constructed in cone shapes using heat-resistant materials and harnessing Iranian wind-catching technology, the yakhchal (or ‘ice pit’) served as an ancient Iranian refrigeration method dating back to around 400 BC. Water sourced from the qanat during winter months would freeze in the yakhchal’s basement, allowing storage of ice blocks for year-round use. Air which is cooled by the subterranean water, entering through qanat shafts, further contributed to temperature reduction.

A UNESCO-listed heritage

“Persian Qanat” was registered on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2016, representing a selection of eleven aqueducts across Iran. According to the UN cultural body, the qanat provides exceptional testimony to cultural traditions and civilizations in desert areas with an arid climate.

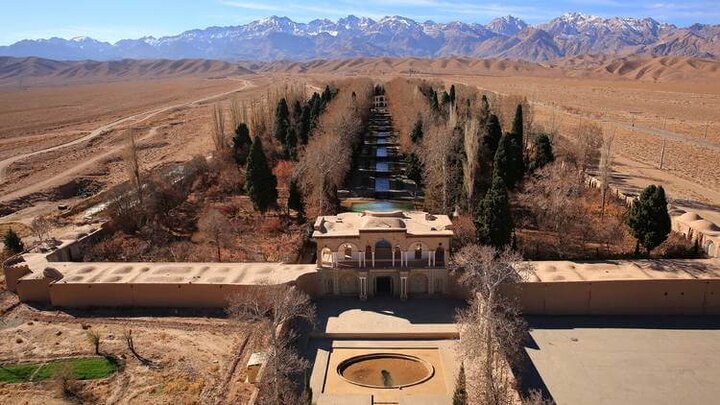

An exemplary illustration exists in Iran’s Fars province, where Persepolis, established by the Achaemenid Persians (550-330 BC), flourished amidst a scorching plain enveloped by the Zagros Mountains. With the aid of qanat-supplied fresh water, Persepolis became the nucleus of an empire stretching from Greece to India—a city renowned for its lavish palaces and exquisite gardens.

The qanat’s efficacy spurred its dissemination worldwide. Initially propagated through the conquests of ancient Persians and later adopted by Muslim Arabs, this system spread as far as Andalusia, Sicily, and North Africa.

Despite technological advancements reducing reliance on qanats in recent decades, these aqueducts remain prevalent across Iran, serving as enduring relics of ingenious ancient engineering.

AFM