Urgent restoration starts on Seyyed Mosque, a lesser-known gem of architecture in Isfahan

TEHRAN – The Qajar-era Seyyed Mosque has undergone urgent restoration work aimed at fixing cracks appearing in its dome and walls.

Over the past three weeks, a team of restorers commissioned by Isfahan’s tourism directorate have been analyzing to find the best possible strategies to deal with the cracks, the provincial tourism chief said.

The project is aimed at reinforcing the whole structure and preventing potentially serious damage triggered by the autumn rains, Hamidreza Mohaqeqian stated.

Referring to the current state of the mosque, the official said: “Unfortunately, for several decades, the heirs of the founder of this historic mosque have been in dispute regarding the management of this mosque, and this point has made it difficult to protect the mosque…”

So, we are working with the provincial authorities to help stabilize the situation of this mosque as soon as possible, Mohaqeqian said.

Covering an area of 8075 square meters, that place of worship, which is somehow a forgotten gem of architecture, is located on a street with the same name.

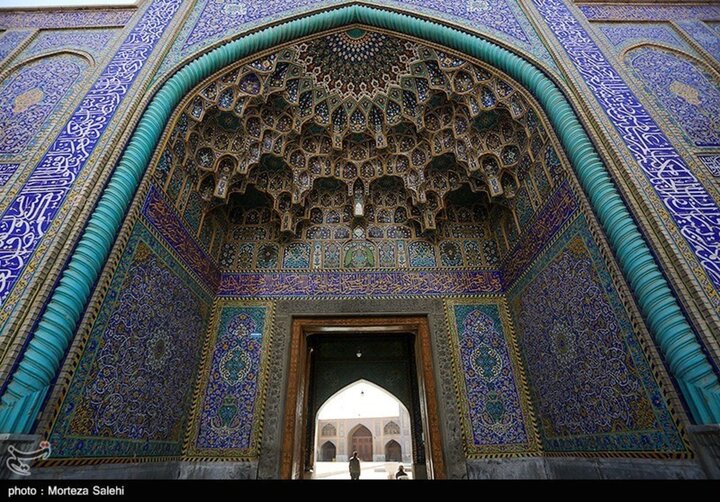

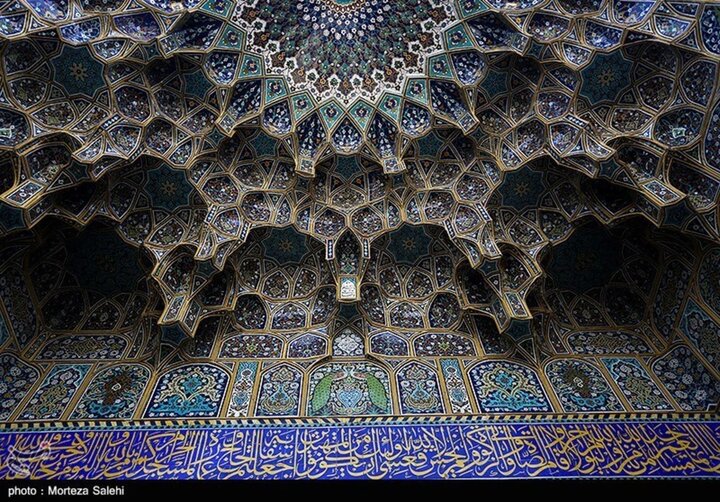

The whole structure of the congregational mosque largely benefited from the flourishing architectural style of the Safavid period and its exemplary decorative arts.

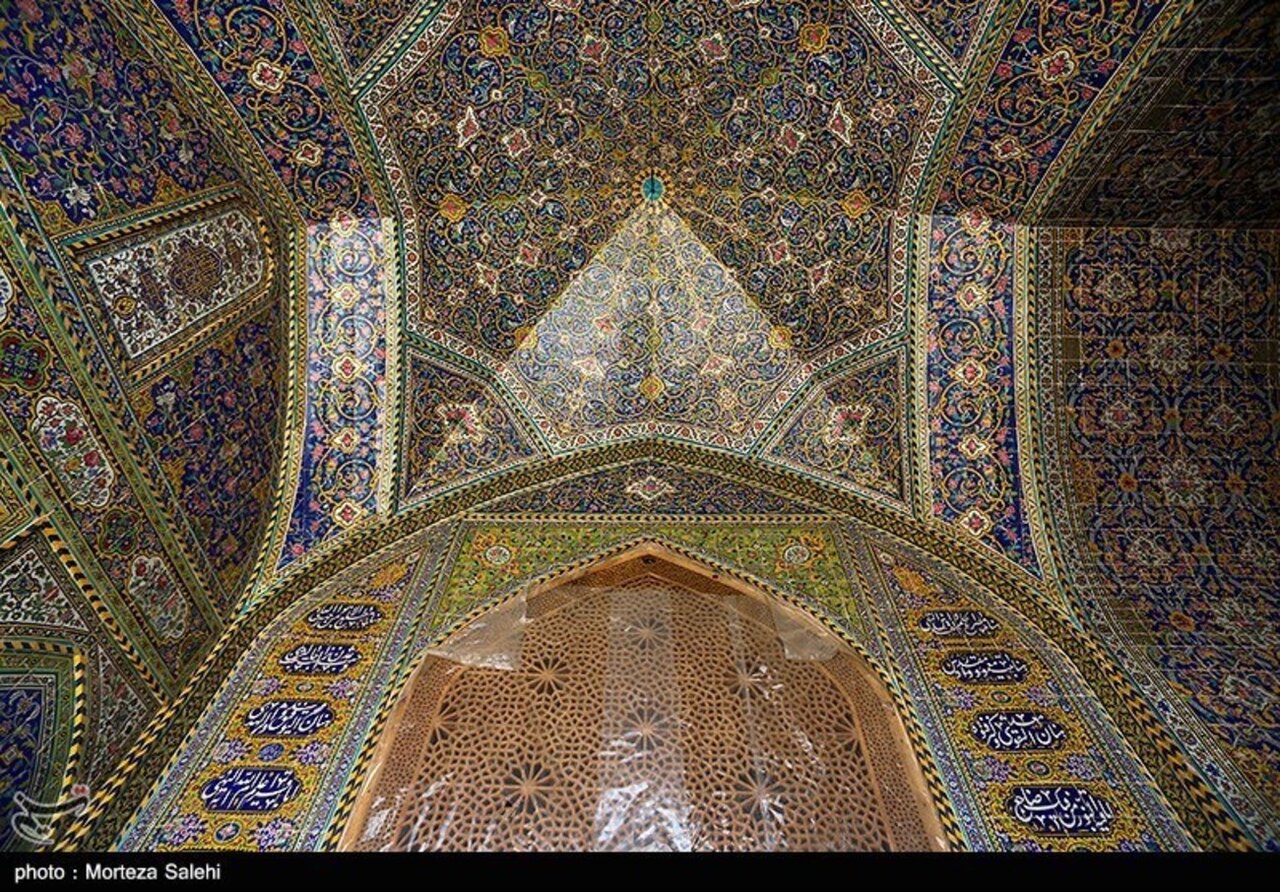

The eye-catching decorations inside the dome include moldings, mirrorwork, geldings, and stuccos, combined with curving calligraphists.

The mosque’s overall tilework is dominated by light red, which can be traced to other mosques of the Qajar era, such as Rahim Khan Mosque and Rokn al-Molk Mosque.

Narratives say that the land of the mosque was bought in the Safavid era, during the reign of Shah Sultan Hossein, but its construction was kept on hold because of the Afghans’ invasion.

Later, during the reign of Mohammad Shah Qajar, the congregational mosque was commissioned by Hojjat al-Islam Shafti, a wealthy religious figure of the Qajar era.

Construction work started in 1825 and the whole process including decoration work took some 130 years.

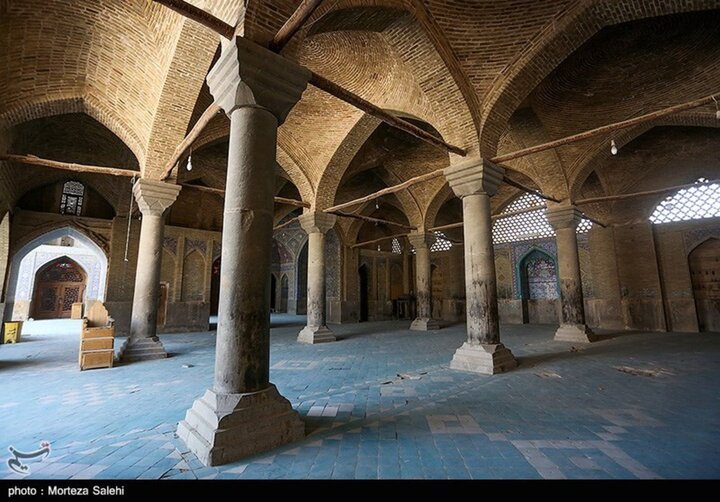

The mosque doubled as a madrasa as well. However, the designers considered no separate space for the education of students. For example, vertical sash windows, which are more common in houses, are applied here to create a proper space for students.

The mosque embraces four main entrances, two spacious Shabestans, a dome, three iwans, and some 45 chambers, but there are no minarets. Shabestan is an underground space that can be usually found in the traditional architecture of mosques, houses, and schools in ancient Iran.

Isfahan was once a crossroads of international trade and diplomacy in Iran and now it is one of Iran’s top tourist destinations for good reasons. When Shah Abbas the Great became ruler of Persia's Safavid dynasty in 1587, he chose Isfahan as his capital and undertook to make it eclipse all other cities. During his reign, he built so many palaces, mosques, gardens, and bridges that the inhabitants boasted: “Isfahan nesfe Jahan”— “Isfahan is half the world.” The subtle nickname implies that seeing Isfahan is relevant to seeing half the world.

Shah Abbas’s immediate successors continued the beautification. According to a contemporary, Isfahan, a city of 600,000, had 162 mosques, 48 colleges, 273 public baths, and no fewer than 1,802 caravanserais, which were open courtyards surrounded with buildings served as medieval tourist parks where travelers could find water for their camels and food and lodging for themselves.

Isfahan is filled with many architectural wonders, such as unmatched Islamic buildings, bazaars, museums, Persian gardens, and tree-lined boulevards. It's a city for walking, getting lost in its mazing bazaars, dozing in beautiful gardens, and meeting people.

AFM