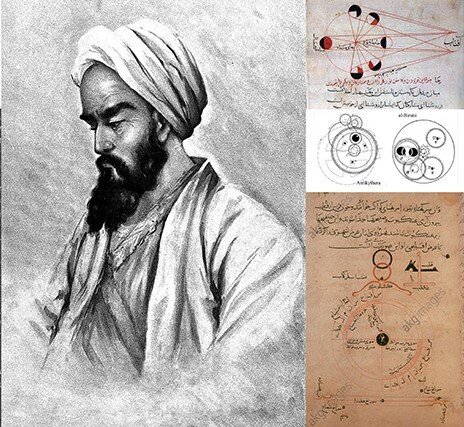

Al-Biruni, the most original polymath in Islamic world

TEHRAN – September 4 is named on the Iranian calendar as the national day to honor Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni, one of the greatest scholars of the Islamic era who was well-versed in physics, mathematics, astronomy, and natural sciences.

Born in the 10th century in Iran’s Khorasan, Al-Biruni was also an ethnographer, anthropologist, historian, and geographer. He became the most original polymath the Islamic world had ever known.

Little is known of the early life of the Iranian scholar and polymath Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni; however, as the name suggests he was born in Beruniy, a small city in Uzbekistan in Western Central Asia which was part of Iran in the past.

Historically, Beruniy was known as Kath and served as the capital of Khwarazm. It is located on the northern bank of the Amu Darya near Uzbekistan's border with Turkmenistan.

Khwarazm is a large oasis region that was the center of the Iranian Khwarazmian civilization, and a series of kingdoms such as the Khwarazmian dynasty and the Afrighid dynasty.

Today Khwarazm belongs partly to Uzbekistan and partly to Turkmenistan.

In 1957, Kath was renamed "Beruniy" in honor of the medieval scholar and polymath Al-Biruni who was born and raised in the town in 973 and died c. 1052, in Ghazna, Afghanistan.

Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni has been variously considered the "Founder of Indology", "Father of Comparative Religion", "Father of modern geodesy", and the first anthropologist.

Al-Biruni spent the first twenty-five years of his life in Khwarezm where he studied Islamic jurisprudence, theology, grammar, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy and dabbled not only in the field of physics but also in most of the other sciences.

Young age

At a young age, Al-Biruni left his hometown for Bukhara, then under the Samanid ruler Mansur II the son of Nuh. and he wandered around Iran and Uzbekistan.

Then, after Mahmud of Ghazni, or Mahmud Ghaznavi conquered the emirate of Bukhara, he moved to Ghazni, a town in today’s Afghanistan, which served as the capital of the Ghaznavid dynasty.

Al-Biruni is most commonly known for his close association with Mahmud Ghaznavi, and his son Sultan Masood.

In 1017, most scholars from different parts of the then Iran, including Al-Biruni, were taken to Ghazni, the capital of the Ghaznavid dynasty. Al-Biruni was made court astrologer and accompanied Mahmud on his invasions into India, living there for a few years.

He was forty-four years old when he went on the journey with Mahmud of Ghazni. Al-Biruni became acquainted with all things related to India. During this time he wrote his study of India, finishing it around 1030. Along with his writing, Al-Biruni also made sure to extend his study to science while on expeditions.

He sought to find a method to measure the height of the sun and created a makeshift quadrant for that purpose. Al-Biruni was able to make much progress in his studies over the frequent travels that he went on throughout the lands of India.

Al-Biruni traveled to many places in India for over 20 years and studied Hindu philosophy, Mathematics, Geography, and religion from the Pundits. In return, he taught them Greek and Muslim sciences and philosophy.

He never exploited his work as a means to achieve fame, authority, or material gains. When Sultan Masood sent him three camel-loads of silver coins in appreciation of his encyclopedic work “Al-Qanoon al-Masoodi,” (The Mas’udi Canon), Al-Biruni politely returned the royal gift saying, “I serve knowledge for the sake of knowledge and not for money.”

Inspired by Al-Biruni

Calculating the radius of the earth over a thousand years ago required a lot of imagination. It was Abu Reyhan Al-Biruni, the 10th-century Islamic mathematical genius, who combined trigonometry and algebra to achieve this very numerical feat.

Biruni’s scholarly legacy has inspired scientists and mathematicians for several centuries, and his name continues to command respect even today.

In 1975, the famous Tajik academician and historian, Bobojon Gafurov, described Al-Biruni in his UNESCO Courier article as a universal genius who “was so far ahead of his time that his most brilliant discoveries seemed incomprehensible to most of the scholars of his days”. George Sarton, the founder of the History of Science discipline, named the 11th century as the Al-Biruni Age.

Scholars like Al-Biruni were born at a time when much of the world’s scientific and mathematical knowledge was translated into Arabic. By the time he came of age, he was also introduced to concepts developed by scholars from different civilizations and centuries.

From the scientific literature of the Babylonians to those of the Romans, to ancient Indian texts on astrology, Al-Biruni learned from it all. Like other Muslim scholars from the Golden Age of Islam, he was also hungry for knowledge.

Al-Biruni's works

Most of the works of Al-Biruni are in Arabic although he seemingly wrote the Kitab al-Tafhim in both Farsi and Arabic, showing his mastery over both languages.

Al-Biruni's catalog of his own literary production up to his 65th lunar/63rd solar year (the end of 427/1036) lists 103 titles divided into 12 categories: astronomy, mathematical geography, mathematics, astrological aspects and transits, astronomical instruments, chronology, comets, an untitled category, astrology, anecdotes, religion, and books he no longer possesses.

The top scholar wrote tens of books, most of which were on astronomical and mathematical subjects. His book on Indian culture is by far the most important of his encyclopedic works.

Listing his works is relatively easy, for he himself produced an index of his works up to when he was about 60 years old. However, he lived well into his seventies, and, since some of his surviving works are not mentioned in this index, the index is a partial list at best.

Adding all the titles in the index, as well as those found later, brings his total production to 146 titles, each averaging about 90 folios. Almost half of the titles were on astronomical and mathematical subjects. Only a minuscule number of his output, 22 titles, has survived, and only about half of that has been published.