Linguists shed new light on Gilgamesh epic using AI tool

TEHRAN - Linguists at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Germany’s Institute for Assyriology say they have created an artificial intelligence (AI) bot to help piece together and decipher illegible fragments of ancient Babylonian texts. “The Fragmentarium” is the name given to it.

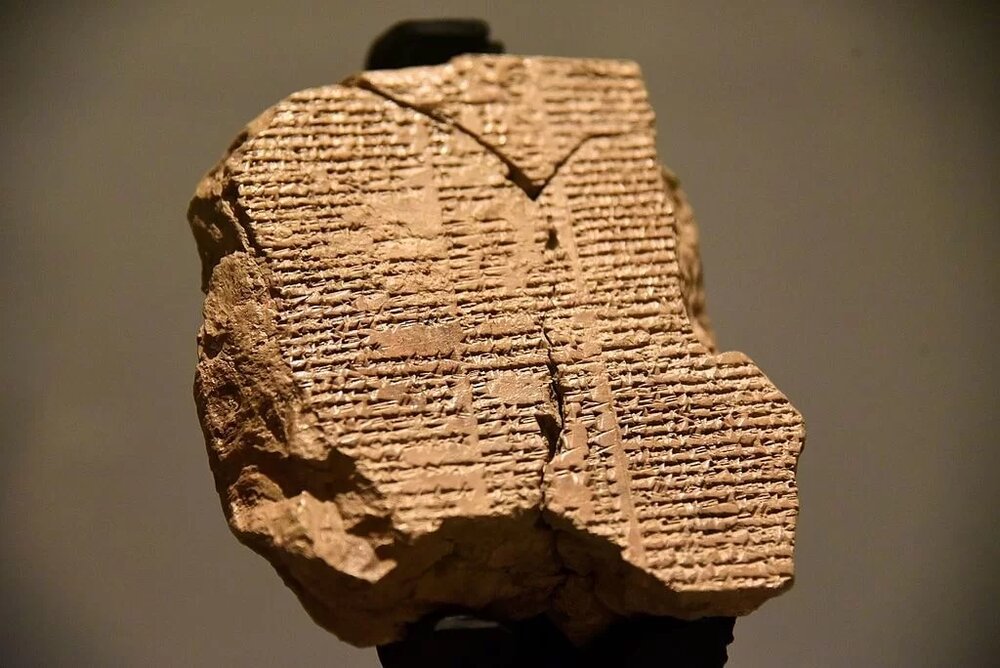

Since 2018, Enrique Jiménez, professor of ancient Near, Eastern literature at the Institute of Assyriology at LMU and his group have been working to digitize every cuneiform tablet still in existence. The project has processed up to 22,000 text fragments during that time.

“It’s a tool that didn’t exist before, a huge database of fragments. We believe it can play a vital role in reconstructing Babylonian literature, allowing us to make much faster progress,” Arkeonews quoted Jiménez as saying on Sunday.

Aptly named the Fragmentarium, it is designed to piece together fragments of text using systematic, automated methods. The designers expect that the program will also be able to identify and transcribe photos of cuneiform scripts in the future. To date, thousands of additional cuneiform fragments have been photographed in collaboration with the British Museum in London and the Iraq Museum in Baghdad.

The team is training an algorithm to piece together fragments that have yet to be situated in their proper context. Already, the algorithm has newly identified hundreds of manuscripts and many textual connections.

According to phys.org, in November 2022, for example, the software recognized a fragment that belongs to the most recent tablet of the Gilgamesh epic, which dates from the year 130 BC—making it thousands of years younger than the earliest known version of the Epic. It is very interesting, remarks Jiménez, that people were still copying Gilgamesh at this late period.

In February 2023, the LMU researcher will publish the Fragmentarium. For the first time, he will also release a digital version of the Epic of Gilgamesh. The new edition will be the first to contain all known transcriptions of cuneiform fragments to date.

Since the project started, around 200 scholars worldwide have had access to the online platform for their research projects. Now it is to be made available to the public as well. “Everybody will be able to play around with the Fragmentarium. There are thousands of fragments that have not yet been identified,” says Jiménez.

Gilgamesh is the subject of many stories in the Akkadian language, and the entire collection has been referred to as an odyssey—the odyssey of a king who did not want to die.

The 12 incomplete Akkadian-language tablets that were discovered at Nineveh in the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–627 BC) contain the most complete version of the Gilgamesh epic. Different fragments discovered elsewhere in Mesopotamia and Anatolia have partially filled the gaps that exist in the tablets.

Additionally, five brief Sumerian poems with the titles “Gilgamesh and Huwawa,” “Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven,” “Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish,” “Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld,” and “The Death of Gilgamesh” have been discovered on tablets that were written during the first half of the 2nd millennium BC.

The prologue of the Ninevite version of the epic is a eulogy for Gilgamesh, who is described as a great builder and warrior who is knowledgeable about all things on land and sea and who is both divine and human. Enkidu, a wild man who initially lived among animals, was created by the god Anu to temper Gilgamesh’s ostensibly strict rule.

AFM