How important was music in ancient Iran?

TEHRAN - Music has long been a significant fragment of life for many ancient cultures. Playing music in celebrations and dances, in sorrows and wars and battles, can be traced through millennia-old bas-relief carvings, clay tablets, and the remnants of primitive instruments.

Researchers disagree on the precise and reliable origin of the first musical sound or the earliest societies that used music, but it is conceivable given that wind and percussion instruments were among the first instruments made by humans.

Early humans noticed melodies being produced near the reeds and when the wind blew through the meadows and in between the reeds, this led people to believe that they could make sound using these reeds.

They built a similar reed based on this concept, so they could use it to signal or warn others. Thus, just as numerous natural phenomena have motivated people to discover and experiment with life’s necessities, it is conceivable that the captivating sounds of the natural world have also influenced the development of various instruments like drums and the like.

Many researchers believe the first indications that someone is listening to music and using it are when people act unusually emotional or raise their voices. Former University of Berlin philosophy professor Karl Stampf recalls the early days of music when people use it to comprehend concepts and think that these sounds are where the science of music began.

According to archeological findings from Elam, the oldest civilization on the plateau in southwest Iran, the earliest complex instruments, which date to the third millennium BC, may have been created there.

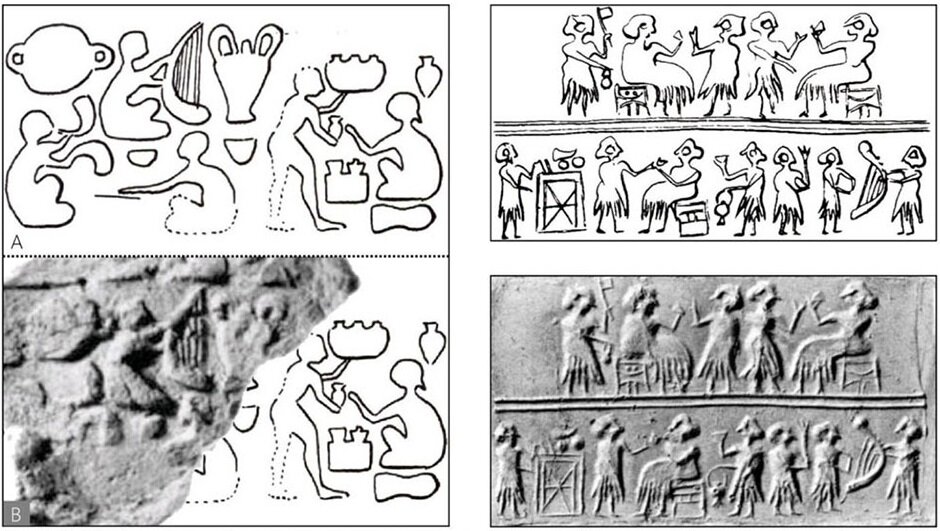

Many trumpets made of copper, silver, and gold that date between 2200 and 1750 BC have been found in eastern Iran by archaeologists and are believed to be from the Oxus civilization. At the archaeological sites of Madaktu (650 BC) and Kul-e Fara (900–600 BC), both vertical and horizontal angular harps were used, with Kul-e Fara having the largest collection of Elamite instruments. Assyrian palaces that date from between 865 and 650 BC also feature numerous sculptures of horizontal harps.

Data regarding the music in Mede’s ear is limited to a few pieces of evidence from Herodotus’ writings. He mentions the Moghs (clergymen) singing some prayers without any instruments accompanying them. This can also be observed in prayers of Zoroastrians that sing the poem-like texts of “Gata”s. The most significant music of that era has probably been the music of Gatas.

As mentioned by Herodotus, music was of grave importance in the Achaemenid era, especially in judging courts. In that epoch, there were three main types of music: war, celebration, and religious music. War music was played during the battles with instruments like “long metal Corna” which was an indication of the glory and popularity of war music in the Achaemenid era. Drums were used to motivate soldiers on the battlefields and Tanbours and Neys welcomed the victorious in the aftermath ceremony.

The Sassanian period (226 CE-651 CE) has left us with a wealth of information indicating the existence of a vibrant musical life. The names of some notable musicians, including Barbod, Nakissa, and Ramtin, as well as the titles of some of their works, have persisted.

By the advent of Islam in the 7th century CE, Persian music and other Persian cultural influences became the primary forming factor in what has been referred to as “Islamic civilization.”

According to Encyclopedia Iranica, Persian musicians and musicologists overwhelmingly dominated the musical life of the Muslim lands. Farabi (d. 950), Ebne Sina (d. 1037), Razi (d. 1209), Ormavi (d. 1294), Shirazi (d. 1310), and Maraqi (d. 1432) are but a few among the array of outstanding Persian musical scholars in the early Islamic period.

In the 16th century, a new “golden age” of Persian civilization dawned under the rule of the Safavid dynasty (1499-1746). However, from that time until the third decade of the 20th century, Persian music became gradually relegated to mere decorative and interpretive art, where neither creative growth nor scholarly research found much room to flourish.

Since the early 20th century, once again, Persian music started to take on wider horizons. There is a growing desire to innovate rather than merely carry on the established tradition and an interest in learning more about the structural components.

Currently, in a progressively modernizing society, they are generally engaged by broadcasting and television media. They also work as teachers, both privately and at various music schools and conservatories.

When it comes to structure, perpetuated through an oral tradition, the classical repertoire encompasses a body of ancient pieces collectively known as the “radif” of Persian music. These pieces are organized into twelve groupings, seven of which are known as basic modal structures and are called the seven “dastgah” (systems).

A piece played twice by the same performer, at the same sitting, will differ in melodic composition, form, duration, and emotional impact due to the basic material’s adaptability and the degree of improvisatory freedom.

AM