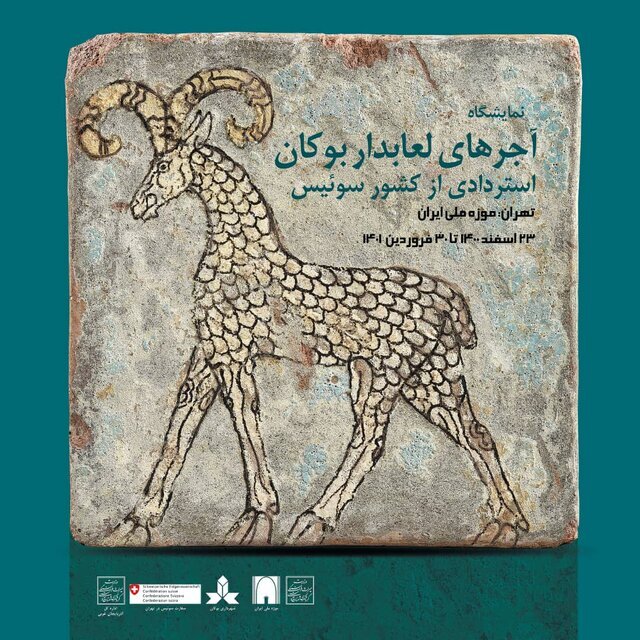

Prehistorical glazed bricks, recovered from smuggler in Switzerland, go on show at Tehran museum

TEHRAN – A collection of prehistorical glazed bricks, which has been recovered from a smuggler in Switzerland, has been put on show at the National Museum of Iran in downtown Tehran.

National Museum of Iran Director Jebrael Nokandeh, and Swiss deputy ambassador to Iran Kim Sitzler were among attendees to the opening ceremony held on Monday, ILNA reported.

Being looted and smuggled out of Iran some four decades ago, the decorated bricks were returned home from Switzerland last year.

Dating back to the 7th or 8th centuries BC, the bricks come from Qalaichi, one of the most important archaeological sites in western Iran, which is just north of the north-western city of Boukan, near the Iraqi border. Qalaichi was the capital of the Mannaean kingdom.

According to The Art Newspaper, the artworks were recovered from a warehouse in Switzerland. The 51 restituted glazed bricks, most just over one square foot in size, have a wide variety of motifs: winged lions and bulls with human heads, mythological figures, birds of prey, deer, and floral or geometric designs.

The artifacts are connected to the Mannai civilization, which was once flourished in northwestern Iran in the 1st millennium BC. Mannai, also spelled Manna, was an ancient country surrounded by three major powers of the time namely Assyria, Urartu, and Media.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the Mannaeans are first recorded in the annals of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (reigned 858–824 BC) and are last mentioned in Urartu by Rusa II (reigned 685–645 BC) and in Assyria by Esarhaddon (reigned 680–669 BC). With the intrusion of the Scythians and the rise of the Medes in the 7th century, the Manneans lost their identity and were subsumed under the term Medes.

In the 1970s, a farmer plowing at Qalaichi came across a decorated brick, probably from the columned hall of its citadel. This discovery led to extremely damaging illegal excavations, partly using a bulldozer. Eventually, in 1985, there was an official rescue excavation, but this was quickly abandoned because of an intensification of the Iran-Iraq war. There were then 14 more years of illegal digging until 1999 when there was another official excavation. But by this time only small fragments of broken bricks were found.

In 1991, an Iranian antiquities dealer with a base in Switzerland contacted John Curtis, the British Museum’s keeper of the Middle East (West Asia) at the time, intending to sell a collection of Qalaichi bricks. Curtis traveled to a warehouse in Chiasso, very close to the Italian border. He warned the vendor that the bricks may have been illegally exported from Iran and advised that they should be returned. His advice was ignored.

The bricks remained in Chiasso for years, but in 2008 the warehouse owners took action after the dealer’s storage bill had remained unpaid. The warehouse obtained authority to seize the contents and on finding the bricks, the Swiss authorities were alerted. Curtis, together with a London-based lawyer, Jeremy Scott, contacted Tehran’s National Museum, which submitted a formal request for their return.

The objects have led to a reconsideration of Mannaean civilization since they show that its people were highly skilled artists. Their designs also reveal a strong Assyrian influence, such as the human-headed winged bulls.

Curtis, who is now the academic director of the Iran Heritage Foundation, says that before the discovery of the bricks, “the richness of Mannaean civilization and its links with Assyria had not been appreciated”.

Composed of 51 pieces of bricks, each bearing a particular figure or motif, the collection will remain on show till April 19.

AFM