Grave hunters: cemetery tourism in Iran

TEHRAN - Having nearly all kinds of historical tombs, museums such as tomb towers, and rack-hewn tombs, Iran is heaven for cemetery enthusiasts and grave hunters; individuals who have passion for and enjoyment of cemeteries, epitaphs, gravestone rubbing, photography, art, and history of famous deaths.

Tourism is one of the fastest-growing phenomena that always makes new changes to have unforgettable experiences, create new travel motivators, and reach new markets. Such a trend results in new tourist spots which were unthinkable only a few years ago!

In cemetery tourism, contrary to popular belief, it is you who will be the protagonist of a hot dialogue of past and present during visits to centuries-old tombs or cemeteries instead of listening to a curator of an exhibition!

It might seem odd but cemeteries as bridges between the present and the past, and the living and the dead, have been drawing their own fans both in groups or individuals each having specific interests.

A cradle of civilization, Iran is well soaked in history and culture, never disappoints cultural travelers with almost every taste even ones interested in cemetery tourism.

Consider Shahr-e Yeri, known as the “city of the mouthless”! It is a unique archaeological site and cemetery in northwest Iran, embracing an Iron-Age fortress, three prehistorical temples, and tens of carved stones on which mouthless faces are depicted, all stretched across 400 hectares of several small hills.

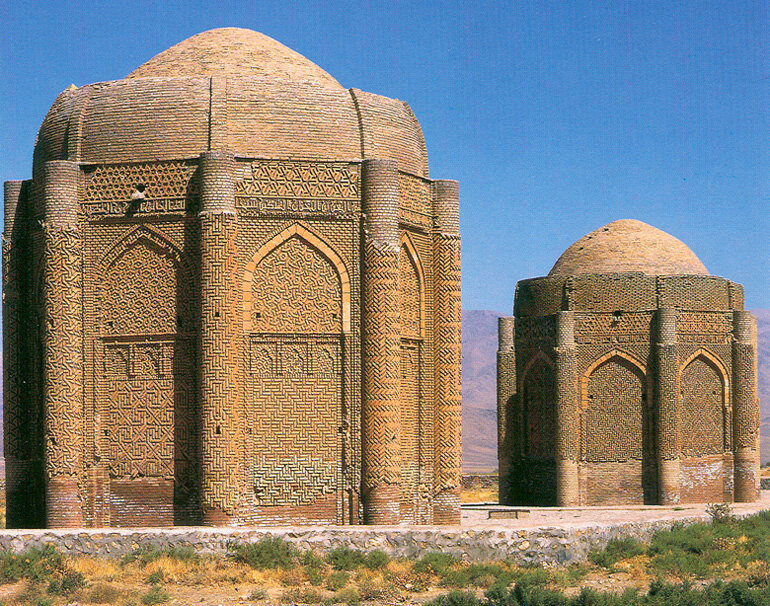

The country is also home to a great number of brick tomb towers. Top on the list may be ones dedicated to the Prophet Habakkuk in Hamedan province. Kharaqan twin tomb towers in Qazvin province and the UNESCO-registered Gonbad-e Qabus in Golestan province are amongst others to name a few.

A variety of spectacular massive rock-hewn tombs and bas-relief carvings at Naqsh-e Rostam has turned the ancient site into a must-see for holidaymakers traversing Iran. The Achaemenid necropolis is situated near Persepolis, itself a bustling UNESCO World Heritage site near the southern city of Shiraz.

Naqsh-e Rostam, meaning “Picture of Rostam” is named after a mythical Iranian hero which is most celebrated in Shahnameh and Persian mythology. Back in time, natives of the region had erroneously supposed that the carvings below the tombs represent depictions of the mythical hero.

One of the wonders of the ancient world, Naqsh-e Rostam embraces four tombs are where Persian Achaemenid kings are laid to rest, believed to be those of Darius II, Artaxerxes I, Darius I, and Xerxes I (from left to right facing the cliff), although some historians are still debating this.

There are gorgeous bas-relief carvings above the tomb chambers that are similar to those at Persepolis, with the kings standing on thrones supported by figures representing the subject nations below. There also two similar graves situated on the premises of Persepolis probably belong to Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III.

Beneath the funerary chambers are dotted with seven Sassanian era (224–651) bas-reliefs cut into the cliff depict vivid scenes of imperial conquests and royal ceremonies; signboards below each relief give a detailed description in English.

Over the past couple of decades, countless archaeological surveys have been yielding ancient tombs, cemeteries many of which bear fresh evidence of ancient burial rituals and entombed objects dedicated to the afterlife.

Years ago, the remains of 13 ancient skeletons, 11 of which human remains, were discovered at olden water ducts of Persepolis, shedding new light on the way of life in the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire.

In another amazing discovery, made in 1993, miners in the Douzlakh Salt Mine of Zanjan Province, accidentally came across a mummified head that was very well preserved to the extent that his pierced ear was still holding the gold earring. The hair, beard, and mustaches were reddish, and his impressive leather boot still contained parts of his leg and foot. In the flowing years, another “salt man” was also discovered one after another at the ancient salt mine. Based on academic studies, their textiles belong to the Achaemenid era (550-330 BC) and the Sassanid period (224 CE–651).

Moreover, a few years ago, the discovery of the skeletons of two Parthian ladies at the ancient Tepe Ashraf in Isfahan cemented a hypothesis that another ancient cemetery is being found within the city, offering valuable clues to uncover the obscure history of pre-Islamic Isfahan.

This way, travel marketers and tour operators contribute to such novel ideas in response to the soaring request of clients for new excitements and knowledge in the search of strange and unique memories.

AFM