Minister visits ancient qanat, says it symbolizes identity of hard-working men

TEHRAN – As one of Yazd’s most important attractions and wonders, the Qanat of Zarch is a symbol of culture, civilization, and identity of hard-working people in central Iran, Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts Minister Ezatollah Zarghami has said.

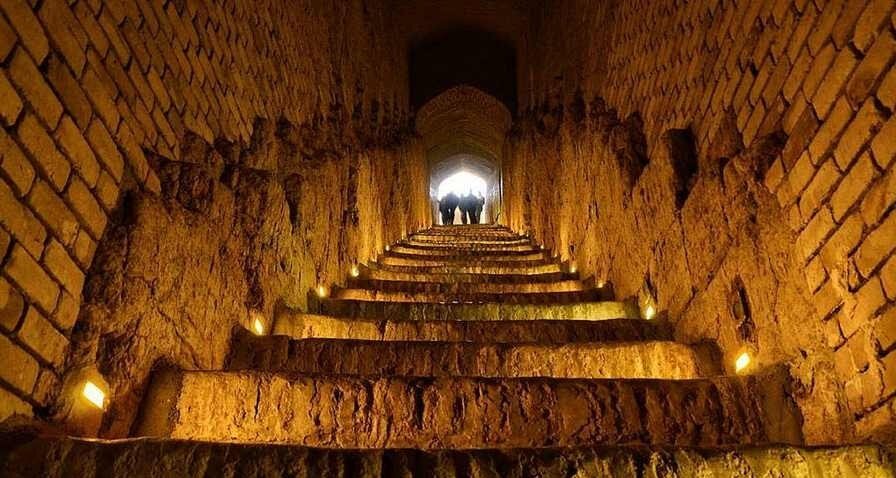

He made the remarks on Thursday during a visit to the ancient qanat, which is widely known as the world’s longest subterranean aqueduct as it stretches some 80 km across the semi-arid Yazd province.

Through the construction of a museum garden nearby, which will showcase the qanat and related structures, tourists will be drawn to this area to learn more about this unique phenomenon, the minister added.

The Qanat of Zarch originated from the village of Fahraj located in the northeast of Yazd and it runs at the depth of 30-40 m beneath the surface. It reaches Zarch, where the water is used for irrigation in the lower lands.

Based on a survey, some 37,000 out of a total of 120,000 ancient subsurface water supply systems, qanats, are still in use in Iran in arid and semi-arid regions of the country.

A selection of eleven qanats is collectively been inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list under the title of Persian Qanat. Each of them epitomizes many others in terms of geographic scopes, architectural designs, and other motives. Such subterranean tunnels provide exceptional testimony to cultural traditions and civilizations in desert areas with an arid climate.

Generally, each qanat comprises an almost horizontal tunnel for collecting water from an underground water source, usually an alluvial fan, into which a mother well is sunk to the appropriate level of the aquifer.

UNESCO has it that “The qanats provide exceptional testimony to cultural traditions and civilizations in desert areas with an arid climate.”

Such constructions are still in practice, many of which were made from the 13th century onwards. Yazd is among ancient cities which have applied this concept to make urban settlements possible in central Iran.

The earliest water supply constructions in Yazd are believed to date from the Sassanid era (224 to 651 CE) while many others have been continually repaired and used over time, most surviving ab-anbars can be today traced to the late Safavid and Qajar periods.

When it comes to landscape architecture, ab-anbars and wind towers play a pivotal role in enriching the Yazd skyline.

The oasis city of Yazd, which is a UNESCO World Heritage, is wedged between the northern Dasht-e Kavir and the southern Dasht-e Lut on a flat plain ringed by mountains.

ABU/AFM