Special exhibit featuring Iranian, German studies on ancient mining opens in Tehran

TEHRAN – On Wednesday, a special exhibition featuring Iranian and German studies on ancient mining and relevant objects was officially inaugurated at the National Museum of Iran.

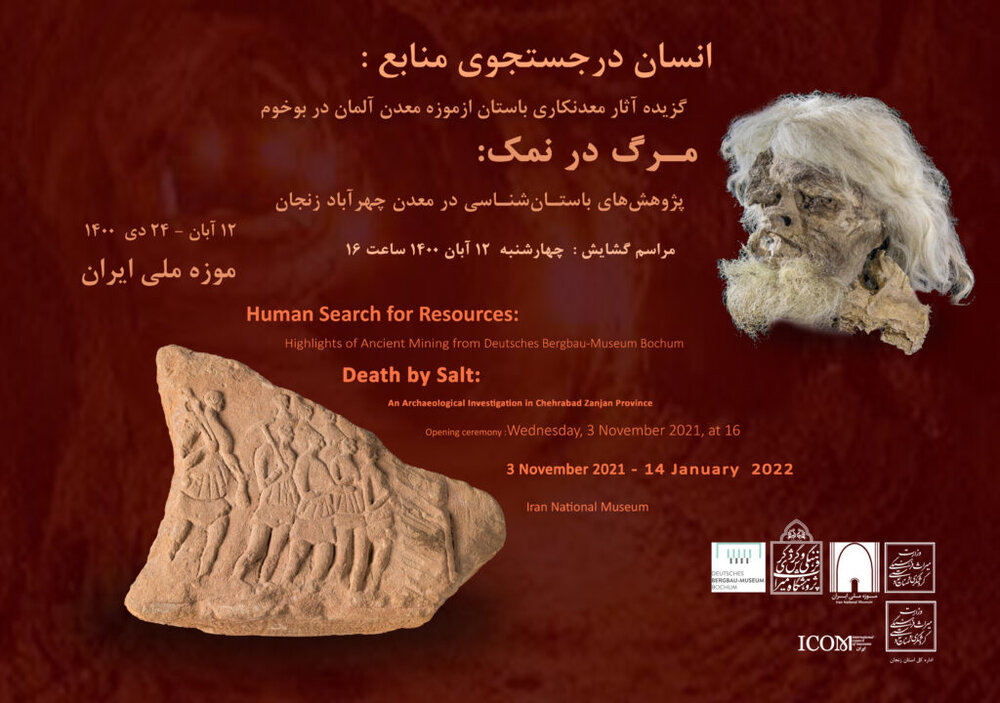

"Highlights of Ancient Mining from Deutsches Bergbau-Museum Bochum", and "Death by Salt" will be running from November 3 to January 14, 2022, at the major museum, which is located in downtown Tehran.

The exhibit puts the spotlight on the appropriation of humans to mineral resources and the development of the history of human experiences and achievements in mining, which led to the development of technologies, the formation of professions, trade, and specialization of industries.

The event showcases arrays of personal objects, tools, and corpses once belonging to the famed Iranian salt mummies discovered in the Chehrabad Salt Mine of Zanjan province.

According to Jebrael Nokandeh, the director of the National Museum, the museum and the German Mining Museum in Bochum have made considerable cooperation in line with an agreement they signed in 2017, based on which the two institutions are set to hold exhibitions of each other's historical and cultural artifacts related to the subject of ancient mining.

It is worth mentioning that similar loan exhibitions featuring ancient mining and relevant documents were already staged in Iran and Germany.

Last year, a team of experts from the two countries started a project for purifying, cleansing, and restoring garments and personal belongings of the mummies which were first found in the salt mine in 1993.

What was a catastrophe for the ancient miners has become a sensation for science. Sporting a long white beard, iron knives, and a single gold earring, the first salt mummy was discovered in 1993. He is estimated to be trapped in the mine in ca. 300 CE. In 2004 another mummy was discovered only 50 feet away, followed by another in 2005 and a “teenage” boy mummy later that year.

In 1993, miners in the Douzlakh Salt Mine, near Hamzehli and Chehrabad villages, accidentally came across a mummified head. The head was very well preserved, to the extent that his pierced ear was still holding the gold earring. The hair, beard, and mustaches were reddish, and his impressive leather boot still contained parts of his leg and foot, according to Ancient History Encyclopedia.

The first mummy, dubbed the “Saltman”, is on display in the National Museum of Iran in Tehran. He still looks very impressive. The third, fourth, and fifth “saltmen” were also carbon dated. The third body was dated and placed in 2337 BP, the fourth body in 2301 BP, and the fifth mummy was dated to 2286 BP, placing them all in the Achaemenid period.

The isotopic analysis of the human remains revealed where these miners were from. Some of them were from the Tehran-Qazvin plain, which is relatively local to the mine’s locality, while others were from north-eastern Iran and the coastal areas around the Caspian Sea, and a few from as far away as Central Asia.

Furthermore, the archaeozoological finds, such as animal bones found within the context of the saltmen, showed that the miners might have eaten sheep, goats, and probably pigs and cattle, as well. The archaeobotanical finds recorded showed different cultivated plants were eaten, indicating an agricultural establishment in the vicinity of the mine.

The wealth of fabric and other organic material (leather) worn by the saltmen have allowed a thorough analysis to be undertaken, detailing the resources used to make the fabrics, the processing, the dyes used to color the fibers of the garments, and not least they offer an excellent overview of the changes in cloth types, patterns of weaving, and the changes of the fibers through time.

Saltman No. 5 had tapeworm eggs from the Taenia sp. genus in his system. These were identified during the study of his remains. The find indicates the consumption of raw or undercooked meat, and this is the first case of this parasite in ancient Iran and the earliest evidence of ancient intestinal parasites in the area. The best preserved and probably the most harrowing of the saltmen is Saltman No. 4. A sixteen-year-old miner, caught in the moment of death, crushed by a cave-in.

The oldest-known mine on archaeological record is believed to be the Ngwenya Mine in Eswatini (Swaziland), which radiocarbon dating shows to be about 43,000 years old. At this site, Paleolithic humans mined hematite to make the red pigment ochre. Moreover, mines of a similar age in Hungary are believed to be sites where Neanderthals may have mined flint for weapons and tools.

AFM