Under one roof: 5,000 years of Iranian arts and culture that are still unknown to many

TEHRAN - Iran has been home to some of the greatest civilizations of both the ancient and medieval worlds, but these achievements are now little known outside the country.

Organized by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, “Epic Iran” showcased how civilized life emerged in Iran around 3,200 BC, and how a distinctive Iranian identity, formed 2,500 years ago, has survived until today, expressed through artistic continuities, religious affiliations, and the Persian language.

The event brought together 250 fascinating objects and images to cast a rare light on 5,000 years of history. It put on show lavishly illustrated manuscripts, metalwork, ceramics, glass, textiles, carpets, oil paintings, drawings, and photographs from collections around the world.

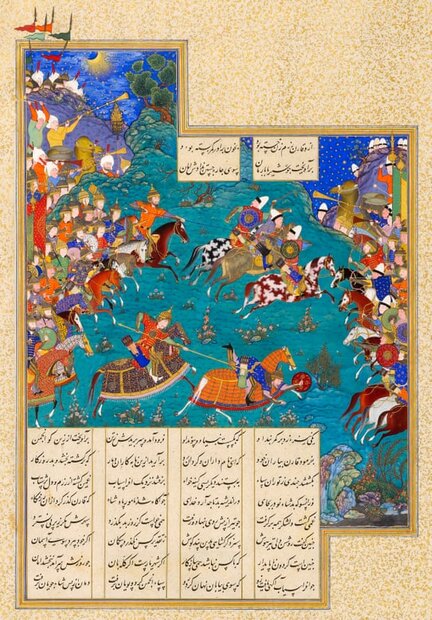

Qaran Unhorses Barman, from the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, about 1523–35. Photograph: © The Sarikhani Collection

Furthermore, the event featured treasures from the ancient and Islamic worlds together with the work of contemporary artists and makers, demonstrating the rich legacy that still influences many modern-day practitioners.

Indian art critic and historian Brijinder Nath Goswamy in his recent article published in The Tribune has said: “In the West, Iran is too often perceived as a black space, literally and metaphorically; unknown, sealed off, frightening. But here (in this exhibition), the country appears before you in full color…”

Armlet, from the Oxus Treasure, 500 – 330 BC, Tajikistan. Museum no. 442-1884. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Goswamy, who is the former vice-chairman of the Sarabhai Foundation of Ahmedabad, begins his article with words from Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire (c.550 – 330 BC):

“I am Cyrus, king of the universe, the great king, the powerful king, king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four quarters of the world…”

“When I went as harbinger of peace i[nt]o Babylon, I founded my sovereign residence within the palace… Marduk, the great lord, bestowed on me as my destiny great magnanimity… and I every day sought him out in awe…”

“I sought the safety of the city of Babylon and all its sanctuaries. As for the population of Babylon, I soothed their weariness; I freed them from their bonds.”

He also presents excerpts from a report by Rachel Cooke, who is a British journalist, writer, and columnist at the Observer:

A couple of weeks back, the Dattas — a generous, gentle Los Angeles-based couple — spoke to me about a great exhibition on Iran and its culture, and said at the same time that they had sent me — being habaaib-e ambar-dast, as the poet Faiz might have put it, ‘friends who have the fragrance of amber on their hands’ — a copy of the book published in conjunction with the show. The book — ‘Epic Iran: 5,000 Years of Culture’, published by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, based on an exhibition of the same name, which ended there at the end of August — arrived and has yielded me so much delight. For it illuminates and informs at the same time: dark corners suddenly springing into light, facts lowering themselves gently into one’s awareness.

Bottle and bowl with poetry in Persian, 1180 – 1220, Iran. Museum nos. C.37-1978 & C.46-1978. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Not exactly at the center of the show, although certainly a significant part of it, was celebrated if contested Cyrus Cylinder — the unbaked clay tablet, pieces of which were discovered in 1879, containing a long pronouncement in cuneiform script by the powerful Achaemenian ruler, Cyrus the Great, “the first attempt we know about running a society, as state with different nationalities and faiths”, “a very early formulation of human rights”.

And that alone might have been reason enough for many to go and see the show. But there were other treasures that led one to an exploration of one of the great historic civilizations of the world. There were clear, finely articulated sections of the show and the book: the Land of Iran with its dramatic and varied landscapes; Emerging Iran engaging with continuous history from 3200 BC; the Achaemenid Period in which, beginning with 550 BC, the powerful Persian Empire established itself; the Last of the Ancient Empires when Alexander the Great overthrew the old dynasts; the Book of Kings, Ferdowsi’s monumental Shahnameh with which virtually began the astonishing literary output of Iran; ending with a look at modern and contemporary Iran with all its struggles. It is as if a great panorama — studded with artistic and literary treasures and vignettes of power — keeps unfurling. Endlessly.

Two figures, 1500-1100 BC, from the Sarikhani Collection. Photograph: © The Sarikhani Collection

In the midst of all this, my great favorite — partly because I know the least about it — is the section in which one sees the early historical period, beginning with the close of the fourth millennium when the light is dim and hazy, and anything found has to be made sense of with the greatest effort. But one begins with that great ziggurat at Chogha Zanbil — a ziggurat being a massive structure in the form of a terraced compound of successively receding stories or levels — with its pure, unadorned brick façade, the structure behind it rising tier upon tier. And then there are those two proto-Elamite tablets of clay, going back to ca 3000 BC that seem filled with abstract signs but have been read, one of them containing an account of ‘five fields and their yields’, with the total inscribed on the reverse.

A highly sophisticated account seems to have been in place. In this very section is a chlorite vase, of classic purity, with concave sides and flaring rim, adorned with carved motifs of date palms. A great surprise at the same time swings into view with a bronze ax-head, now brilliantly mottled in color, which has the figures of two wrestlers grappling each other at the back of the socket. The details of the wrestlers’ forms are dazzling: they both have hair ribbons knotted at the back of the head, and the manner in which one wrestler has the other in a headlock, and grasps his opponent’s leg with the other hand, takes one’s breath away.

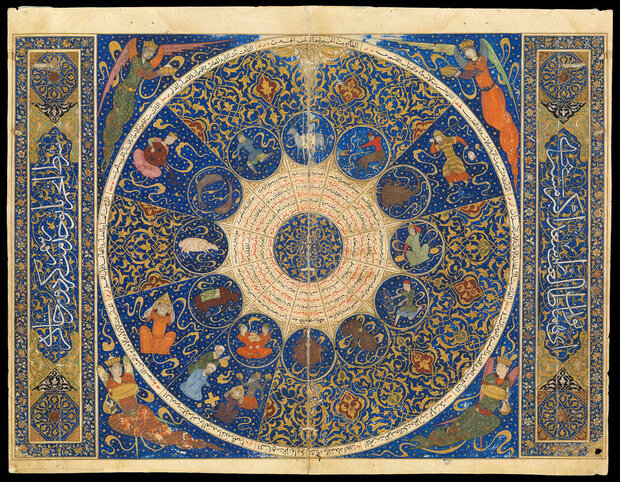

Horoscope of Iskandar Sultan, 1411. © Wellcome Collection

For a great exhibition like this, the sponsors, the organizers, must draw upon several museums, several collections, and they did. Objects came from the Louvre, from the Metropolitan Museum, from the National Museum of Iran, the Museum of Art and History at Brussels, and so on. But a large number of objects in the exhibition came from a relatively little-known source: the Sarikhani collection. Little known because it is quietly tucked away in a private underground museum near Henley in Oxfordshire: rich in manuscripts, textiles, silverware, glass, paintings, and ceramics from 3000 BC to the 18th century: all from Iran.

“Epic Iran”, which ran from May 29 to September 12, marked a fresh climate of cultural cooperation between Iran and the West as mutual political tensions seems to be heightened behind the scene.

AFM