Relic attributed to Neo-Assyrian king discovered in western Iran

TEHRAN – Iranian archaeologists have discovered a portion of a royal memorial inscription, which is attributed to a Neo-Assyrian king, in western Iran.

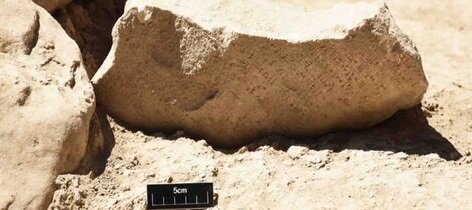

“During an excavation project in Qabaq Tappeh of Kermanshah province, a team of Iranian archaeologists has unearthed a portion of a royal memorial inscription, which is attributed to Sargon II, who was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire,” ISNA quoted archaeologists Sajad Alibeigi, who leads the survey, as saying on Monday.

However, the royal inscription, which bears 23 lines of writing in cuneiform, is so far deemed as the most significant discovery of the survey, according to the archaeologist.

“Qabaq Tappeh was once an important and extensive settlement inhabited at least from the third millennium BC to the Islamic era,” Alibeigi noted.

Sargon II, (reigned 721–705 BC) extended and consolidated the conquests of his presumed father, Tiglath-pileser III. Upon his accession to the throne, he was faced immediately with three major problems: dealing with the Chaldean and Aramaean chieftainships in the southern parts of Babylonia, with the kingdom of Urartu and the peoples to the north in the Armenian highlands, and with Syria and Palestine.

By and large, these were the conquests made by Tiglath-pileser III. Sargon’s problem was not only to maintain the status quo but to make further conquests to prove the might of the god Ashur, the national god of the Assyrian empire.

Assyria was a kingdom of northern Mesopotamia that became the center of one of the great empires of the ancient Middle East. It was located in what is now northern Iraq and southeastern Turkey.

Assyria was a dependency of Babylonia and later of the Mitanni kingdom during most of the 2nd millennium BC. It emerged as an independent state in the 14th century BC, and in the subsequent period it became a major power in Mesopotamia, Armenia, and sometimes in northern Syria. Assyrian power declined after the death of Tukulti-Ninurta I (c. 1208 BC). It was restored briefly in the 11th century BC by Tiglath-pileser I, but during the following period, both Assyria and its rivals were preoccupied with the incursions of the seminomadic Aramaeans.

According to Britannica, the Assyrian kings began a new period of expansion in the 9th century BC, and from the mid-8th to the late 7th century BC, a series of strong Assyrian kings—among them Tiglath-pileser III, Sargon II, Sennacherib, and Esarhaddon—united most of the Middle East, from Egypt to the Persian Gulf, under Assyrian rule.

The last great Assyrian ruler was Ashurbanipal, but his last years and the period following his death, in 627 BC, are obscure. The state was finally destroyed by a Chaldean-Median coalition in 612–609 BC. Famous for their cruelty and fighting prowess, the Assyrians were also monumental builders, as shown by archaeological sites at Nineveh, Ashur, and Nimrud.

AFM/