Glimpses of bread making in Iran

Since the olden days, bread has been the staple diet of the folks living in the semi-arid Iranian plateau. Traditional and ethnic Persian breads are famed for their strong flavor, quality, and diversity.

The Persian word for bread is “nan” which you can find in great works by nearly all top Iranian poets and literary men, both modern and classics such as Ferdowsi, Khwaja Abdullah Ansari, Rumi, Saadi, Ebne Yamin, Saib Tabrizi, and Sohrab Sepehri.

Among the Iranian nation, “nan” is recognized as “barakat” meaning God’s blessing. Iranians treat bread with respect due to its holy place in their ancient culture.

“Nan” can also be traced in the Sasanian inscriptions of the third century CE. Also, analyzing historical documents show that the word “nan” is mentioned in the Pahlavi texts of the 9th century. A definition of sangak—one of the most popular Iranian breads—was found in the comprehensive Persian encyclopedia “Borhan-e-Ghate” in 1651.

The traditional Persian cuisine is interwoven with a wide variety of breads due to two main reasons. Firstly, bread is considered as the main food of the Iranian people and its consumption in the daily diet is very common. Secondly, Iran is an integrated country that accommodates various ethnic communities.

Iranian flatbread is produced by cooking fermented dough, basically made from wheat flour, yeast, and water. Several additives may be added to the wheat flour-yeast-water dough to increase the shelf life of bread and improve its sweetness, quality, or even nutritional value.

The most commonly used additives are vegetables (such as potato, onion, and spinach), fruits and nuts (such as raisins, walnuts, and peanuts), seeds (such as poppy, cumin, and sesame), salt, sugars, lipids, milk, egg, spices, and food starches.

In addition to countless kinds of flatbread that are baked throughout the country, numerous types of bread are produced by the ethnic groups. Sangak, barbari, taftoon, and lavash are the most popular kinds of bread, which are prepared in different composition, shape, size, texture, color, and flavor.

Flatbreads may be categorized in different ways as below: By the type of flour: wheat-based, barley-based, rice-based, etc. By the size and volume: flat, raised, and semi-raised. By method of cooking: hot stone-baked, tandoori, oven-baked, steam-baked, etc. By the type of ingredients added to wheat flour-water-yeast dough: sesame bread, potato bread, etc. By texture: doughy, soft, crispy, brittle, and dry. And finally, by whether or not the bread contains sugar: sweet and nonsweet.

Here are some of the most popular flatbreads ubiquitous in every corner of the country, and even beyond:

Nan-e sangak

Sangak, a thin and flatbread, is one of the most common and popular breeds in the country. It is considered as one of the national breads of Iranian cuisine. Its shape can be either triangular or rectangular, and it comes in two main varieties: plain and special, which is topped with poppy and sesame seeds.

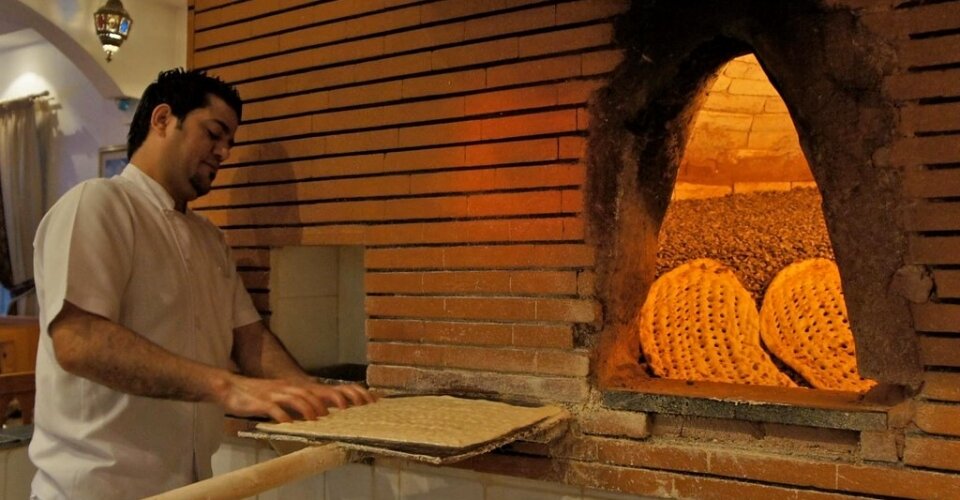

Historical documents show that this bread was probably invented by the scholar and chief architect Shaykh Bahai during the Safavid dynasty. What is unique about the sangak bread is the way of baking in a traditional oven. Sangak in Persian means “pebble” or “small stone.” This bread is baked on a bed of hot pebbles in an oven.

At least two bakers are required to prepare sangak. The dough is flattened on a slightly convex slab and is quickly thrust into the oven by the first person. Another baker removes sangak with a double-prong fork or skewer after a few minutes. Fig. 1 shows the two types of sangak bread.

Nan-e barbari

Nan-e barbari is wheat-based and leavened flatbread. It is usually formed into a long oval shape that is traditionally brushed with rooms, a flour glaze which gives it a light golden crust but keeps it light and airy on the inside.

Barbars were an ethnic group indigenous to northeastern Iran that borders Afghanistan. They brought this bread to Tehran during the Qajar ear. The baker rests the flattened dough on a table for preparation for the baking process. Sprinkling seeds such as sesame over the dough is very common before baking. Finally, the dough is carefully inserted with a long wooden paddle into a heated oven.

Nan-e taftoon

Taftun or taftoon, is a Persian word that is derived from “tafan”, meaning “heating”, “burning”, or “kindling.” The flatbread is almost always prepared with whole wheat flour, milk, eggs, and yogurt. The dough is similar to pizza dough, resulting in a chewy, stringy texture. Traditionally, the dough is baked on the walls of a tandoor oven for about a minute and is then removed from the walls with a metal skewer.

Nan-e taftoon is often flavored with cardamom or saffron, while some cooks like to sprinkle it with poppy seeds on top. The bread is mostly eaten with kebabs, but it can be consumed with virtually anything on the side, such as cottage cheese, tomatoes, and bell peppers.

Nan-e lavash

Lavash is a soft and thin flatbread that is prepared in a clay oven, rotary oven, baking machine, or tandoor. It is one of the most widespread types of bread in Iran. The origin of lavash is most probably from Iran, according to the state of the encyclopedia of Jewish food.

There is a tremendous variety in flavor and texture of this bread in Iranian cuisine. Some types of lavash are so thin that they will be dried quickly and a brittle and hard texture will be achieved. Also, lavash varies in size from about 30 cm in length to over 0.5 m, and in shape from circular to oblong or square.

Nan-e shirmal

Shirmal is a traditional Iranian flatbread made with maida flour, milk, saffron, and yeast. It is characterized by its strong saffron flavor and yellow color. The bread is traditionally baked in a tandoor oven and served warm, preferably with soups or meat dishes such as kebabs and curries.

The name shirmal means milk bread, referring to one of its key ingredients, imparting a slightly sweet flavor to the flatbread. For additional sweetness, some cooks like to add dried fruit into the dough. It is believed that shirmal has Persian roots, when numerous Persians traveled to India and Pakistan and learned the secrets of bread-making.

AFM/