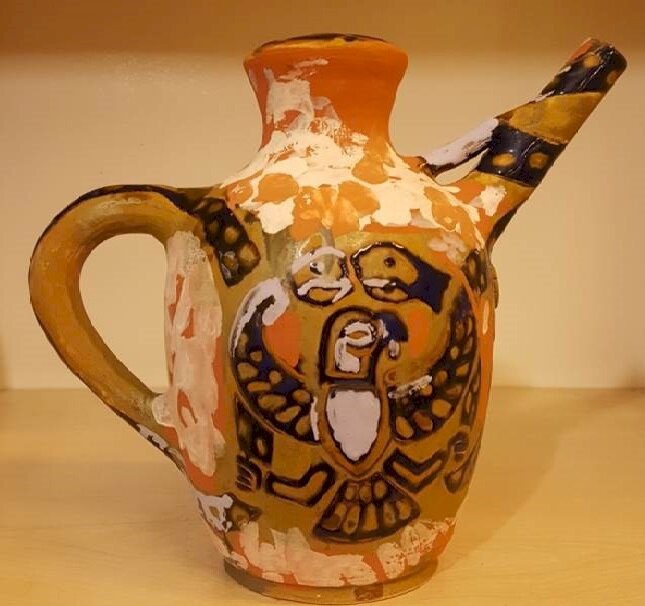

Replica of prehistorical ‘alchemy’ vessel built by Iranian potters

TEHRAN – A group of Iranian researchers and potters has reconstructed a replica of a prehistorical vessel, which is believed to be used for alchemy, a form of speculative hypothesis tried to transform base metals such as lead or copper into silver or gold and to discover a cure for disease and a way of extending life.

“A replica of a clay vessel belonging to the first millennium BC, which is said to be once an alchemy instrument, is made by the artists of a pottery workshop of the Research Institute of Cultural Heritage & Tourism,” CHTN quoted Seyyed Abdolmajid Sharifzadeh, who presides over the traditional arts group of the institute, as saying on Saturday.

“The [original] earthen vessel, which was the subject of this research was unearthed in the village of Kaluraz, Rudbar county, Gilan province,” Sharifzadeh said.

Such a vessel has also been discovered in Jiroft of Kerman province, he added. Jiroft is one of the richest historical areas in the world, with ruins and artifacts dating back to the third millennium BC. Many Iranian and foreign experts believe the findings in Jiroft as signs of a civilization as great as Sumer and ancient Mesopotamia.

“Unlike other types of pottery, which are made to hold liquids such as water and are filled from above, this pottery, which is shaped like a teapot, is filled from the bottom and its upper side is closed.”

He also explained the pottery can be used for traditional distillation, and concentrate (separation of substances) in ancient chemistry.

“This pottery is also referred to as an alchemical vessel,” Sharifzadeh said.

A closer look at alchemy

Alchemy was the name given in Latin Europe in the 12th century to an aspect of thought that corresponds to astrology, which is an older tradition. Both represent attempts to discover the relationship of man to the cosmos and to exploit that relationship to his benefit. The first of these objectives may be called scientific, the second technological. Astrology is concerned with man’s relationship to “the stars” (including the members of the solar system); alchemy, with terrestrial nature.

But the distinction is far from absolute since both are interested in the influence of the stars on terrestrial events. Moreover, both have always been pursued in the belief that the processes human beings witness in heaven and on earth manifest the will of the Creator and, if correctly understood, will yield the key to the Creator’s intentions, according to Britania.

Superficially, the chemistry involved in alchemy appears a hopelessly complicated succession of heatings of multiple mixtures of obscurely named materials, but it seems likely that a relative simplicity underlies this complexity.

The metals gold, silver, copper, lead, iron, and tin were all known before the rise of alchemy. Mercury, the liquid metal, certainly known before 300 BC, when it appears in both Eastern and Western sources, was crucial to alchemy.

Sulfur, “the stone that burns,” was also crucial. It was known from prehistoric times in native deposits and was also given off in metallurgic processes (the “roasting” of sulfide ores). Mercury united with most of the other metals, and the amalgam formed colored powders (the sulfides) when treated with sulfur. Mercury itself occurs in nature in a red sulfide, cinnabar, which can also be made artificially. All of these, except possibly the last, were operations known to the metallurgist and were adopted by the alchemist.

The alchemist added the action on metals of several corrosive salts, mainly the vitriols (copper and iron sulfates), alums (the aluminum sulfates of potassium and ammonium), and the chlorides of sodium and ammonium. And he made much of arsenic’s property of coloring metals. All of these materials, except the chloride of ammonia, were known in ancient times.

Finally, the manipulation of these materials was to lead to the discovery of the mineral acids, the history of which began in Europe in the 13th century. The first was probably nitric acid, made by distilling together saltpetre (potassium nitrate) and vitriol or alum. More difficult to discover was sulfuric acid, which was distilled from vitriol or alum alone but required apparatus resistant to corrosion and heat. And most difficult was hydrochloric acid, distilled from common salt or sal ammoniac and vitriol or alum, for the vapors of this acid cannot be simply condensed but must be dissolved in water.

AFM/