The seeds of civilization

TEHRAN – Paleolithic sites in Iran are known primarily from caves and rock shelters in the central Zagros mountain range along with a few sites on the Caspian Sea coast and scattered sites on the desert plateau. They were predominantly attractive living places for the hunter-gatherers and early cave-dwelling man.

The first systematic investigations of Paleolithic archaeology in Iran was carried out in the mid-20th century by American anthropologist Carleton Stevens Coon (1904 – 1981), who was a professor of anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, lecturer and professor at Harvard University, and the president of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, according to Encyclopedia Iranica.

Between 1925 and 1934, Coon conducted fieldwork in North Africa, the Balkans, Ethiopia, and Arabia. In 1948 he left Harvard to become professor of anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania and curator of general ethnology at the University Museum. Beginning in the next year, he conducted excavations in Persia, Afghanistan, and Syria.

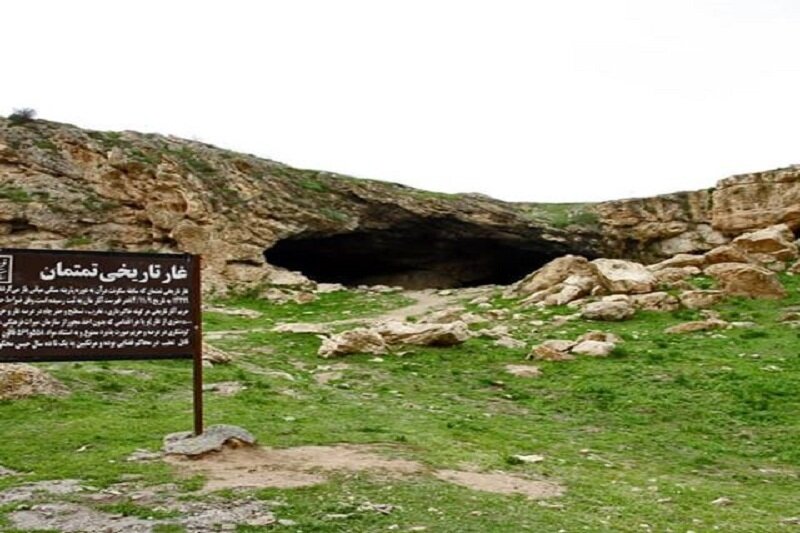

Coon published numerous general works on anthropology and the ethnography of Islamic peoples from Morocco to Afghanistan. His interest in the origin of races and fossil man led him to undertake in 1949 the first systematic search for Paleolithic remains in Iran, where he carried out excavations at the Hunters' Cave at Bisotun, at Tamtama Cave near Urmia, and at Khunik Cave near Birjand in Khorasan. The latter two caves yielded a few atypical Mousterian artifacts and the one at Birjand also some animal bones indicating that it had been used as a warm-weather hunting site.

The Hunters’ Cave produced a full range of the Mousterian stone-tool industry in association with bones of gazelles, red deer, and equids, as well as a fragment of a human arm bone (called “Neanderthaloid” by Coon).

The site, located above the famous Bisotun spring, was probably a camping spot for hunters. In 1992 this site was still the only fully published Paleolithic excavation site in Iran.

Coon concluded in 1957 that the Persian plateau had probably been an area of transit, rather than an area for the emergence of the earliest Upper Paleolithic. It appears that Persia had already assumed the role it has continued to play ever since, that of intermediary between the cultures of the Near East, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.

In 1949 and 1951 Coon also excavated what he called “Mesolithic” caves (the term has now been replaced by “Epipaleolithic”) in the cliffs on the southeastern Caspian shore near Sari: the Belt Cave (Ghar-e kamarband) and Hotu Cave.

The caves became habitable around 9800 BC., as the Caspian Sea retreated about 10 km toward the present shoreline. A variety of local animals were eaten, including seals, sheep, goats, gazelles, voles, and birds.

The Belt Cave produced bone tools, hand stones and querns, microliths, and heavier blades and flakes. Hotu Cave contained amorphous flakes and pebble tools, but no microliths. This difference in the remains from adjacent sites remains unexplained.

The discovery of partial skeletal remains of six people is the only known evidence for the human Epipaleolithic population of the territory that is now Persia. These individuals are described as fully modern, tall, with well-formed muscles; they probably lived about forty years.

The bodies, sprinkled with red ocher, represent the earliest deliberate burials known in the region. These burials were both primary and secondary in nature and date to between 7000 and 6500 BC.

Coon thought in 1957 that these remains reflected a form of incipient Neolithic culture, as simple pottery, polished stone, and some domesticated goats and sheep were found in the same levels, but it is now clear that this material overlaps the Neolithic of the western Zagros at Ganj Dareh.

According to the late Prof. Ezzat. O. Negahban, a more detailed picture of early cave-dwelling life has been developed for the Zagros region where traces of cave dwellers from the Lower Paleolithic to the Middle Paleolithic, Upper Paleolithic, and Epipaleolithic periods have been found. That’s because the Zagros highlands have generally been subject to more Stone Age research and investigation than have the Alborz mountain range.

The Paleolithic or ‘Old Stone Age’ begins with the first stone tools some 2.5million years ago in Africa, and it ends with the Neolithic or ‘New Stone Age,’ essentially at the beginnings of agriculture. The Paleolithic is conventionally divided into Lower, Middle, Upper, and Terminal or Epi-Paleolithic periods. The Paleolithic is known almost exclusively from lithic artifacts—stone tools, classified in conventional ways into types that are diagnostic of the various periods.

There is virtually no information about the perishable tools and devices made of wood, fiber, or skins that may have been in use. Layers in archeological sites typically contain quantities of lithics, bones of animals that were hunted and consumed, and the ash from domestic fires.

AFM/