Cyrus Cylinder: the story of 2,600-year-old icon of freedom

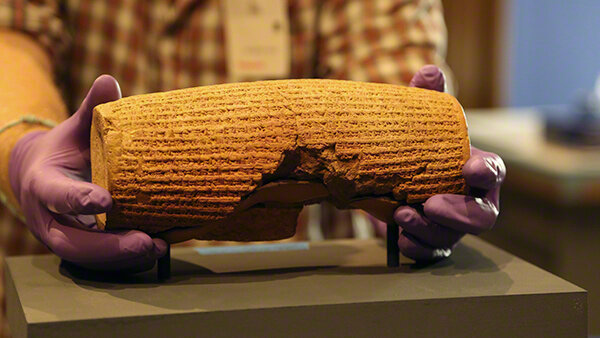

TEHRAN - The 2,600-year-old Cyrus Cylinder is a small barrel-shaped clay cylinder, almost the size of an American football, which was inscribed in enigmatic-looking cuneiform on the order of the Persian King Cyrus after he captured Babylon in 539 BC.

The Cyrus Cylinder, which is being kept at the British Museum, bears many insights and links to a past that we all share and to a key moment in history that has shaped the world around us.

Famed as the “first bill on human rights”, the clay object’s inscriptions appear to encourage freedom of worship throughout the Persian Empire and to allow deported people to return to their homelands.

The cylinder was buried under the walls of Babylon in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) after Cyrus had captured the ancient city. It was concealed undisturbed for more than 2,400 years until it was dug up in 1879 by a British Museum excavation led by Hormuzd Rassam.

The cylinder was buried under the walls of Babylon in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) after Cyrus had captured the ancient city. It was concealed undisturbed for more than 2,400 years until it was dug up in 1879 by a British Museum excavation. When the Babylonian cuneiform was deciphered and translated, it was immediately realized that the cylinder had a very special significance. It describes how Cyrus was able to defeat the Babylonian king Nabonidus with the aid of the Babylonian god Marduk, who had run out of patience with Nabonidus and his shortcomings.

Once Cyrus and his army entered the city, they did not burn it to the ground (as usually happened with conquered cities at this period) but he freed the population from forced labor obligations, sent back to various shrines statues of gods, and allowed the people who had been brought to Babylon by the Babylonian kings to return to their homes. By this act, he was effectively allowing people to pursue unmolested their own religious practices.

The empire, founded by the Persian kings Cyrus and Darius, stretched from the Balkans to Central Asia at its peak. It was the first state model based on diversity and tolerance of different cultures and religions.

The cuneiform text

The text, according to Ancient History Encyclopedia, can be divided in two parts: Lines 1 to 18 tell a story of Cyrus' deeds in the third person: the document tells of Nabonidus, the last Babylonian king, who is said to have forbidden the cult of Marduk among others, and to have oppressed his subjects. Consequently, the subjects made complaints to the gods, and Marduk found Cyrus in order to make him the world’s ruler. All the inhabitants of his new empire then became very happy to see him as their new king.

In the second part, Cyrus speaks in the first person. He begins with his titles, and continues saying that he took care of the Marduk’s cult at Babylon and that he had “allowed them to find rest from their exhaustion, their servitude”. He also tells that lots of kings bring to him levies, and that he restored the cults in all the former kingdoms which are now part of his, and that he released the former deported persons.

Different readings of this document can be and have been made: Formerly some specialized historians took the text as a testimony close to reality, but today this interpretation is mostly out of use.

Some others see in this document confirmation of the Bible in its historicity, with Marduk assimilated to Yahve. In fact in the Bible Cyrus is shown as Yahve’s object, who gives to him the power to create his kingdom and the will to release captive Jews and help them to rebuild their temple. In fact, the cylinder shows Cyrus saying: “the gods who dwelt there I returned to their home and let them move into an eternal dwelling. All the people I collected and brought them back to their homes,” (line 32) which could be the confirmation of releasing captive Jews, even if these are not named in the text. One thing is clear: Cyrus chose to show that he has one powerful God at his side, Marduk, who gives him the legitimacy to overthrow Nabonidus and conquer his empire.

Many historians today agree that this document is propaganda, in which Nabonidus is treated worse than he was, using for this false portrayal of the Marduk cultists’ anger against the last Babylonian king.

A recent current theory is to understand the Cyrus Cylinder as the first charter of human rights. This interpretation began when, in 1971 CE at the 2500th birthday of the Persian monarchy, the Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi made Cyrus the Great a key figure in government ideology, in order to establish a pre-Islamic legitimacy of his government. The same year, his dynasty offered a replica of the Cyrus Cylinder to the United Nations, with an English “translation” that is largely truncated and manipulated in order to show that Cyrus made the first charter of human rights.

The problem is that this latter translation is largely diffused by the UN and on the web, contributing to this idea, while speaking of human rights or charter is an anachronism. In fact, Cyrus had effectively made a policy of tolerance in some minor points, especially regarding the cults, and this policy was continued by his successors over 200 years after. But taking “(…) find rest (…) from their servitude (…)” (L.26) as the abolition of slavery, for example, is a total anachronism, as the existence of multiple kinds of slaves during Achaemenid rule proves. We surely should understand these tolerance policies more as a way to quickly associate new subjects in his empire, in order to have the least troubles possible therein.

Exhibition history

The Cyrus Cylinder has been displayed in the British Museum since its formal acquisition in 1880. It has been loaned four times – twice to Iran in October 1971 and again from September–December 2010, once to Spain from March–June 2006, and once to the United States in a traveling exhibition from March–October 2013.

In 2005–2006 the British Museum mounted a major exhibition on the Persian Empire, Forgotten Empire: the World of Ancient Persia. It was held in collaboration with the Iranian government, which loaned the British Museum a number of iconic artifacts in exchange for an undertaking that the Cyrus Cylinder would be loaned to the National Museum of Iran in return.

AFM/MG