Discover Istakhr, ancient royal residence near legendary Persepolis

TEHRAN – The ancient city of Istakhr, which was once a royal residence for Sassanid kings of Persia, is located in the vicinity of the UNESCO-registered Persepolis.

From one point of view, its history stretches back to 224 CE, when a Persian nobleman named Ardashir, son of Papak, son of Sasan, dethroned the lawful ruler in Persia, Artabanus IV, king of the Parthian Empire.

As one of his residences, according to livius.org, the new ruler chose Istakhr: situated near Persepolis, the capital of the Achaemenids, it allowed the new Sasanian dynasty to identify itself with a glorious past. The builders of Istakhr often reused architectural elements from the monuments of Persepolis. The Achaemenid royal tombs of Naqsh-e Rostam are not far from Istakhr too.

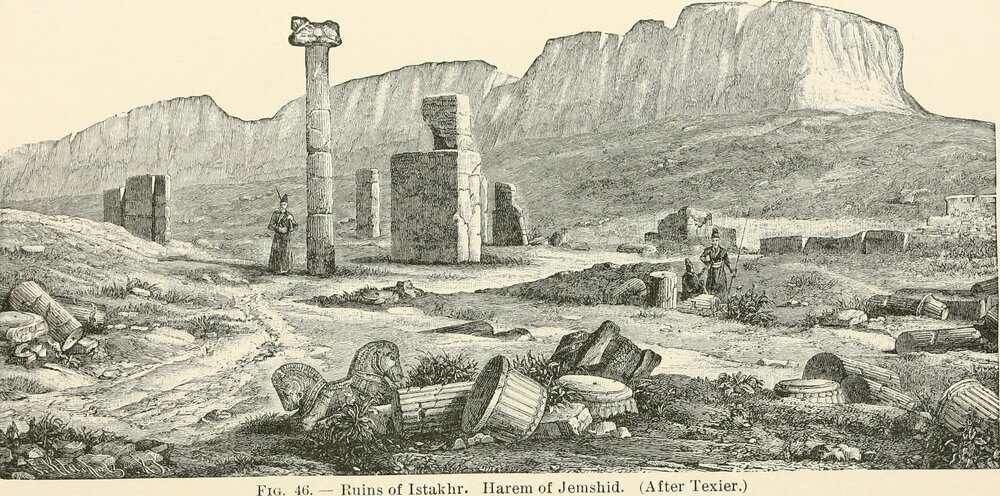

A drawing from the ruins of Istakhr in the 19th century

The city itself was not completely new: human occupation had started as early as the fourth millennium BC, and the site was certainly occupied in the Bronze Age, by the Achaemenids, by the Seleucids (who used it as a mint town), and by the Parthians.

The city, which had strong walls, repulsed the first Arab attack in c.644, but was captured and sacked in c.650. Although the site was not really abandoned, most people moved to Shiraz (which was founded in 684).

Once, as an Islamic town, it was enclosed by fortification walls with rounded towers.

According to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, the geographer Istakhri wrote that in the tenth century, its houses were built of clay, stone or gypsum-according to the wealth of their owners.

The ancient trash pit at Istakhr proved to be a very valuable source of finds. The entire site is perforated by a number of refuse, sewage or storage wellholes. The holes are often “locked” by caps of brick or stone, and therefore an approximately contemporaneous mixture of broken and discarded pots, personal ornaments, stone and bronze objects, and a large amount of coins was preserved in them.

Among the kinds of pottery excavated from the Islamic stratum, molded ware is found very frequently. These light-green vessels were not only of very high quality but also manifested a unique method of pottery making. The upper and lower halves, with their sculptured decorations, were always molded separately; the two halves, often showing the same pattern, were then joined together.

Also from the Islamic period, but less frequent, are pitchers with floral designs in red, yellow, and black. Unfortunately, excavations of the site produced only a few of the famous and very rare lusterware vessels with their metallic sheen over a golden-yellowish body. There is considerable controversy about this pottery and whether it was produced in Iran or imported from Mesopotamia.

Among other finds were clay figurines of animals. There were also stone and bronze objects, such as lamps, small vessels, and a number of utensils used in daily life. Also found were objects of iridescent glass and personal ornaments ranging from clay to gold.

Today, Istakhr is nothing but a plain full of sherds, scattered architectural remains, and a few ruins. The walled-in area measured 1,400 x 650 meters and was surrounded by a ditch that was connected to the river Pulvar.

Under the Sasanians, Iranian art experienced a general renaissance. Architecture often took grandiose proportions, such as the palaces at Ctesiphon, Firouzabad and Saravan.

Amongst most characteristic and striking relics of the Sassanids are rock sculptures carved on abrupt limestone cliffs, for example at Shapur (Bishapour), Naqsh-e Rostam, and Naqsh-e Rajab. Metalwork and gem engraving became highly sophisticated.

AFM/MG