A peek into Iranian art and architecture under Sassanids

TEHRAN – In many ways, Iran under Sassanian rule witnessed tremendous achievements of Persian civilization. Experts say that during Sassanid era (224-651 CE), the art and architecture of the nation experienced a general renaissance.

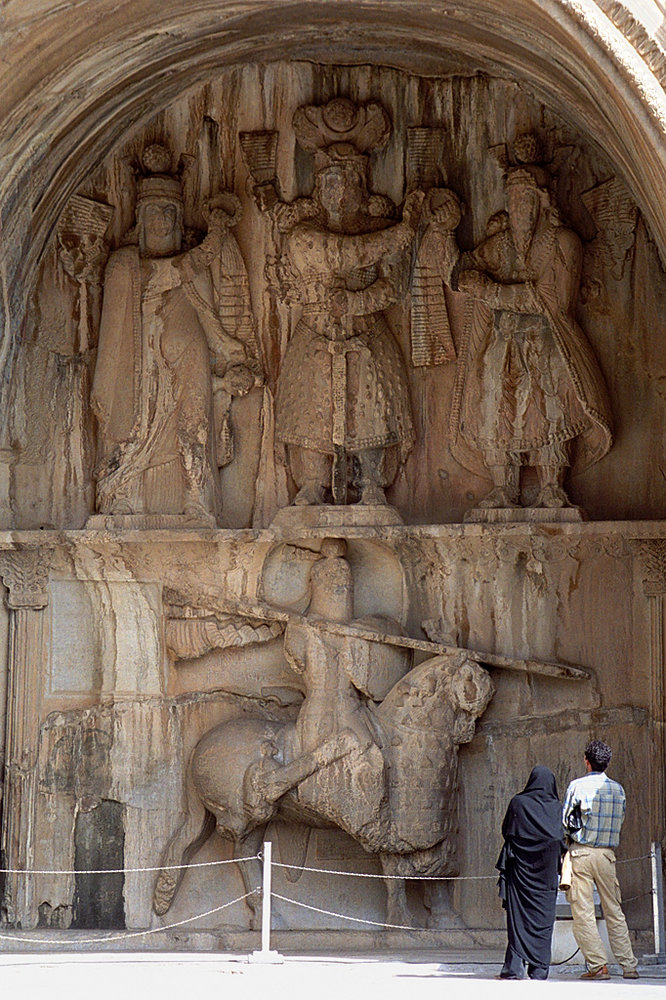

Rock-carved bas-reliefs are widely deemed as the most impressive and best-known works of Sassanians, of which about thirty are known from the first two centuries of Sassanian rule. The largest number is in Fars, in the majestic silent valley of Naqsh-e Rostam, in the small bay of rocks at Naqsh-e Rajab, on the steep inclines of a gorge at Bishapur. There are also other examples across the country.

In 2018, UNESCO added “Sassanid Archaeological Landscape of Fars Region”, which is an ensemble of Sassanian historical cities in southern Iran, to its World Heritage list. The property comprises eight archaeological sites, including fortified structures, palaces and city plans in Ctesiphon, Firuzabad, and Sarvestan, all located in modern Fars province.

UNESCO says that the archaeological landscape reflects the optimized utilization of natural topography and bears witness to the influence of Achaemenid and Parthian cultural traditions and of Roman art, which had a significant impact on the architecture of the Islamic era.

In that era, crafts such as metalwork and gem-engraving grew highly sophisticated, as scholarship was encouraged by the state; many works from both the East and West were translated into Pahlavi, the official language of the Sassanians.

Among the most distinctive products of Sassanian art, according to Iran Chamber Society, are the plaques of molded and carved stucco which covered the crude masonry of brick or rubble.

However, excavations in villas surrounding the royal palace of Ctesiphon showed that rich stucco decoration was used only in the principal hall and perhaps in the room directly adjoining it, while other rooms had merely a covering of plain gypsum plaster.

Of all the material remains of the era, only coins constitute a continuous chronological sequence throughout the whole period of the dynasty. Such Sassanian coins have the name of the king for whom they were struck inscribed in Pahlavi, which permits scholars to date them quite closely.

The legendary wealth of the Sassanian court is fully confirmed by the existence of more than one hundred examples of bowls or plates of precious metal known at present. One of the finest examples is the silver plate with partial gilding in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Encyclopedia Britannica states that a revival of Iranian nationalism took place under Sassanid rule. Zoroastrianism became the state religion, and at various times followers of other faiths suffered official persecution. The government was centralized, with provincial officials directly responsible to the throne, and roads, city building, and even agriculture were financed by the government.

At the time of Shapur I (reigned 241–272), the empire stretched from Sogdiana and Iberia (Georgia) in the north to the Mazun region of Arabia in the south; in the east it extended to the Indus River and in the west to the upper Tigris and Euphrates river valleys.

The dynasty was destroyed by Arab invaders during a span from 637 to 651.

AFM/MG