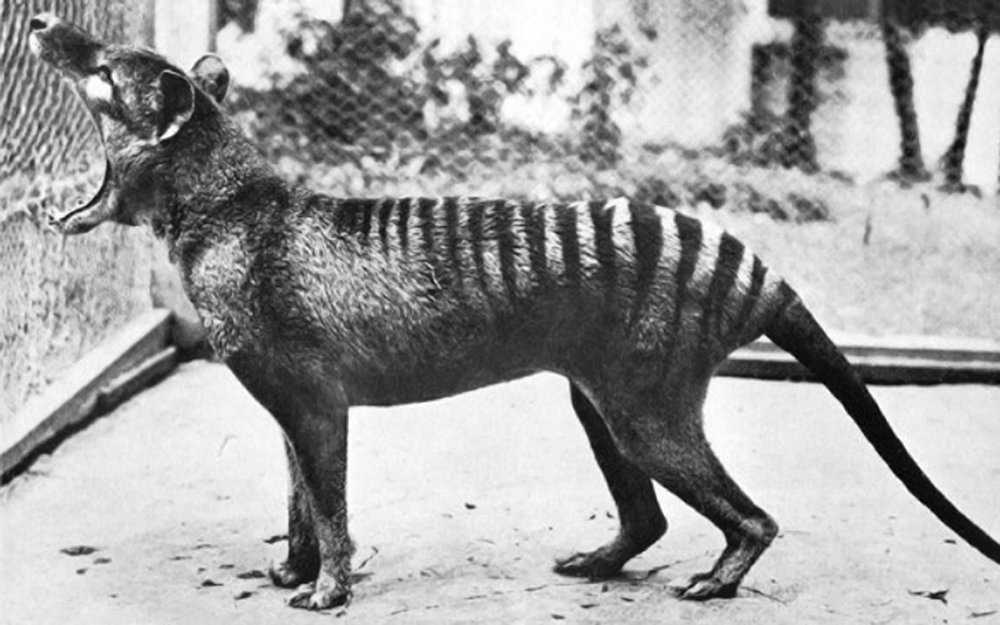

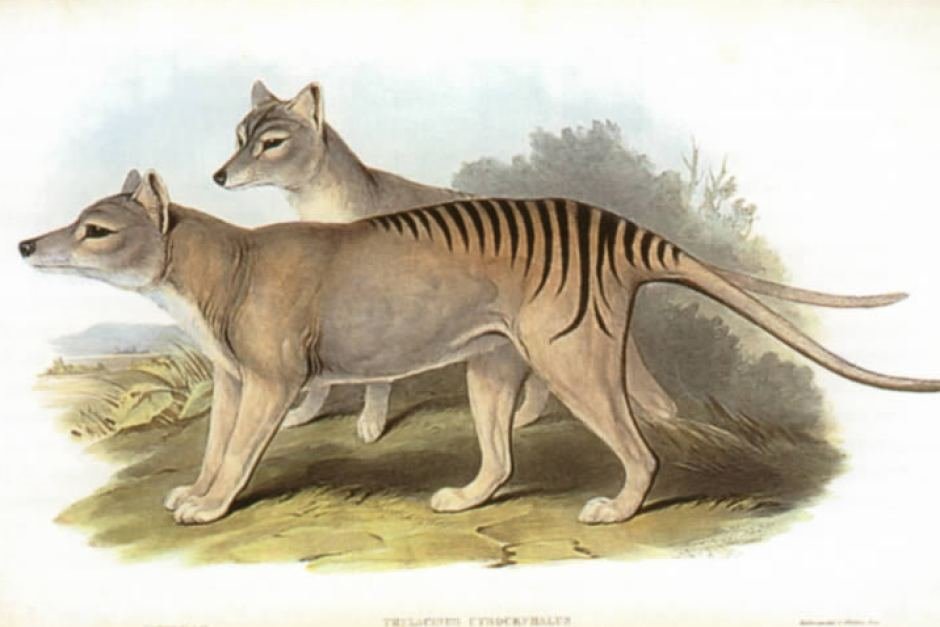

Dragged to extinction by dogs and cats

The thylacine -a marsupial- was once prevalent across Australia and Tasmania. Today it seems that domestic dogs and other introduced animals have outcompeted the species. It was also persecuted by farmers and is now extinct, although there are continued reports of sightings but all are inauthentic.

The last wild known Thylacine was captured in 1933 and lived alone in Hobart Zoo, Tasmania, where it died in 1936. Despite numerous, including contemporary, reports of its existence, and several organized searches, there has been no irrefutable evidence of its survival.

The thylacine has no close relatives. Once placental mammals such as dingoes and, later foxes and domestic dogs and cats reached Australia, the thylacine was forced to compete with these more efficient hunters and killers. It swiftly disappeared from its former wide range, although there were many reports of sightings on the mainland of Australia, even into the early 20th century.

Fossils reveal

About two years ago, an international team of scientists studied 2,000 fossils from North America. Fossils showed two species have a rocky past after the introduction of cats to Americas. This introduction ended in a disastrous influence for the continent’s species of wild dogs. Jack Millner wrote in his article of daily-mail: “In fact, it is thought that competition from cats caused up to 40 species of dog to become extinct in the region millions of years ago. The introduction of cats from Asia into the Americas 18.5 million years ago is thought to have drastically decreased the biodiversity of dogs, according to researchers.”

Genetic dilution

Like many predators, the wildcat has suffered extensive persecution. Today the major threat to its survival is genetic dilution of the species as it increasingly interbreeds with domestic cats. The wildcat is a solitary and secretive animal found mainly in forested areas across continental Europe and in Scotland. Its range also extends east to the Caspian Sea. The biggest threat by far to wildcats is “genetic pollution” through interbreeding with domestic cats. The wildcats of Europe are so similar to the African Wildcat (from which the domestic form is thought to originate) that some zoologists think the two species are actually the same. They are certainly closely related, which is why they interbreed so easily. As a result, the natural wildcat population has begun to include crossbred animals (hybrids).

This genetic dilution undermines the purity of the species. Ironically, as the wildcat’s habitat has shrunk, the animal has been forced into new areas where it encounters domestic cats more often. This has led to more interbreeding and further genetic dilution. Thus the greater the wildcat’s breeding success, the more uncertain its future becomes. At the very least, hybridization will result in a confused picture, with some areas having true wildcats, and others having hybrids. In addition, interbreeding makes the species difficult to monitor.

The Berne Convention, the European Union Habitats Directive, and the national legislation of many countries recognize the wildcat’s rarity and have given the animal legal protection. Yet these laws are unable to prevent the main threat of interbreeding. Moreover, since hybrids are not legally protected, the legislation is weakened because anyone killing a wildcat can claim that they thought the animal was a hybrid. Such an assertion cannot be easily disproved. If wildcats and domestic cats really are the same species then it seems impractical to give the animal legal protection, since there are millions of house cats all over the World!

Limited knowledge

As people and their domestic animals have spread and increased in number, conflict with wildlife has escalated, resulting in extermination of wildlife in many parts of their range. Today leopards, cheetahs, wolves, foxes and many others are still unwelcome residents across much of their range. Our wildlife heritage is rapidly vanishing, perhaps hastening into extinction by many reasons such as unknown disease that swept through domestic dogs and maybe cats. The main problems plaguing the wildlife throughout their range are all too familiar but introduction threats are still in doubt by public.

Dr. George Schaller known as one of the founding fathers of wildlife conservation, is the Vice President Emeritus at Panthera. Born in Germany in 1933, he has worked for nearly two decades studying and developing conservation initiatives for the snow leopard, Tibetan antelope, and wild yak, among other species.

His most recent conservation projects have been based in Laos, Myanmar, Mongolia, Iran and Tajikistan. Last year he had visited cheetah habitat in Iran; in fact he has made five trips to Asiatic cheetah habitat since 2000. He addressed many threats that Asiatic Cheetah faces, many threats are indirect and less obvious- cars, dogs, and gazelle poachers on high-speed motorcycles for example head up a list of threats and all take a toll.

Cheetahs are vulnerable to the large, powerful, and often nearly feral mastiff-type dogs who accompany herdsmen into parks. Schaller said to wbur’s the Wild Life: “It is known that five cheetahs have been killed in the past three years by these dogs.” And he argues that the dogs are unnecessary to the shepherds—they don’t actually herd sheep and goats, and they are not needed to protect the flocks since the shepherds are always with them. “Dogs should be completely banned from national parks and wildlife refuges,” Schaller writes to wburs.

In fact the problem of dogs and cats is an extension of one of the oldest battles in nature- that of competition between animals for space. In this contest, one species competes more aggressively for space than any other. The problem of dogs and even cats is vast and widespread in our national parks and wildlife refuges, and it is just a reality that affects animals of all kinds.