The political legacy of Imam Khomeini

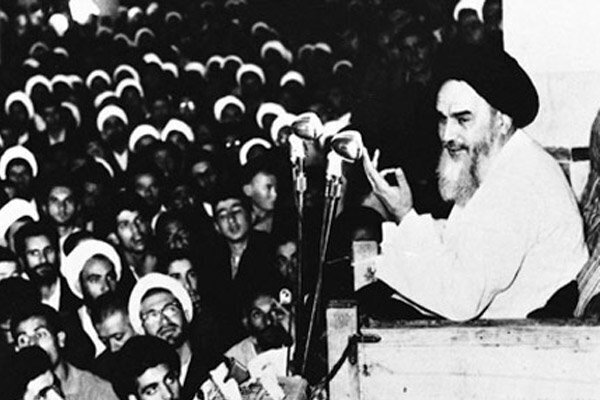

MADRID – On the 36th anniversary of the passing of Imam Ruhollah Khomeini, the central figure of the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, his thought continues to influence not only the political trajectory of the Islamic Republic but also broader debates about the relationship between Islam and politics in the Muslim world.

Far from being a mere regime change, the Islamic Revolution represented, for many of its supporters, a profound rupture with the dominant modern political paradigm. At the heart of this movement was a key idea: Islam should not be reduced to a purely spiritual or ritual practice but could offer an alternative model of political, cultural, and social organization, articulated from its own tradition.

Islamism, understood as the political formulation developed by Ayatollah Khomeini, according to which Islam must occupy a central place in the public sphere and in the configuration of power, displays several defining traits. Among them is the conviction that the West has lost its normative hegemony; the overcoming of the nation-state as the sole legitimate political framework; and the need for an Islamic power capable of representing and defending the umma—the global community of believers—on the international stage.

In this context, the Islamic Republic of Iran presents itself as a political actor with autonomous representational capacity, independent from the dictates of Western powers and articulated through its own political grammar.

Imam Khomeini understood that the orientalist gaze remained the dominant prism through which Muslim societies outside the Eurocentric narrative were interpreted. This outlook assumes that Western ideology—with its categories, methods, and values—is universal, valid for analyzing and explaining any reality, even those foreign to its historical and cultural origins.

Islamism, however, challenges this premise. From this perspective, the West is not defined as a concrete geographic space but as an ideology: a thought system that presents itself as neutral while actually imposing its own epistemic limits when interpreting the non-Western. The Islamist critique is therefore not only political but also epistemological: it questions the legitimacy of the conceptual framework used to understand the Islamic world.

According to Islamists, the Western normative view starts from the assumption that Islam cannot serve as a valid political tool. From this standpoint, presenting Islam as a political identity alternative to the Pahlavi regime would be dismissed as a distraction from the real, deeper causes of the revolution. Islam, in this narrative, is reduced to a mere epiphenomenon—a smokescreen without power to transform the political order.

Imam Khomeini’s thought emerged in opposition to Eurocentrism. The revolution was not only the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979) but also a break with the orientalist framework that portrayed Muslims as lacking political agency. This opposition manifested in a cultural transformation aimed at the “de-Westernization” of Iranian society.

The 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran has been subject to many interpretations, ranging from sociological and theological to geopolitical and cultural analyses. However, it has rarely been approached as an epistemic event in the fullest sense, not merely as a regime change or a historical anomaly, but as a rupture that destabilizes the very frameworks through which politics has been conceived in modernity.

From this theoretical vantage point, the Islamic Revolution is neither a theocratic regression nor an exception within the secularization process but an epistemic break: a radical questioning of the modern political order founded on theological-Christian sovereignty. What is at stake is not only the ideological content of a new state but the very configuration of the political field as constituted by Western thought. In this sense, the revolution can be interpreted as an attempt to reconfigure the political from a different place, outside the Western paradigm that reduced the Islamic to the premodern or irrational.

Islamist historiography views this revolution as the first that did not follow Western political grammar, making it unpredictable for scholars and experts. A recurring example is the book Iran: Dictatorship and Development, written by Fred Halliday just months before the 1979 revolution. In this work, Halliday attempts to foresee possible scenarios after the fall of the Pahlavi dynasty, which was already evident. However, among his many predictions, he never considered the possibility of an Islamic revolution, instead proposing options such as a nationalist government, socialism, or even a new monarchy.

The absence of the Islamic revolution from such predictions allowed Islamists to criticize Western political perspectives, which, they argue, were incapable of conceiving Islam as a political tool. In other words, the possibility of using Islamic language to achieve political emancipation was, and remains, unimaginable within the Western narrative.

Imam Khomeini constructed an autonomous identity with Islam as its nodal point. According to this interpretation, the founder denied the universality of Western epistemology while simultaneously challenging the historical sequence known as “from Plato to NATO.”

The revolution materialized as an Islamic identity embedded in an alternative genealogy of anti-colonial resistance, with its own grammar that cannot be expressed in the Western language of national liberation or Marxism.

Thus, Imam Khomeini, through his political thought, answered one of the most pressing questions for Islamism: how can Muslims live politically, as Muslims, in the contemporary world?

Imam Khomeini’s importance lies in his political project, which aimed—and succeeded, in displacing the West as the normative discourse. This process was carried out using exclusively the language of the Islamic tradition, without any reference to political doctrines considered Western, unlike other Islamic reformists.

Imam Khomeini wrote as if Western grammar did not exist. For his followers, this irrelevance was fundamental, as it meant the materialization of an autonomous Muslim political identity. That Imam Khomeini wrote as if the West did not exist also implies that Islam cannot be reduced to the category of “religion.”

From this perspective, the idea of “religion” is a product of the European Enlightenment, a model that has been globally exported. Accepting the universalization of the category “religion” ignores that it is a project attempting to present European local history as a universal narrative. Islamism denounces this imposition of Western epistemic norms over Islamic traditions.

Religion as a colonial category

The idea that there exists something universal under the name of “religion” assumes a transhistorical essence that overlooks the differences among the various projects invoking the figure of God. From the perspective of the Islamic Republic, speaking of “religion” implies accepting its character as a private belief, separate from politics, as understood in the West. For this reason, discourse on religion can only be fully understood in relation to the narrative of secularism.

Secularism should not be understood simply as the absence or exclusion of religion from the public sphere, but as a normative project that establishes its own boundaries. For the Islamic Republic, secularism is neither natural nor the culmination of a historical process; rather, it is a disciplinary discourse, a political modality that validates certain political sensitivities while excluding others by deeming them threats.

The use of religious language is not merely a descriptive exercise but carries a clear prescriptive intention: the ultimate goal is to regulate the space of Islam.

Imam Khomeini captures this idea that Islam cannot be reduced to the colonial category of “religion” when he states:

“If we Muslims did nothing but pray, beg God, and invoke His name, imperialists and oppressive governments would leave us alone. If we had said: let us focus all our energies on the call to prayer for 24 hours and simply pray, or: let them steal everything we have, for God will take care of it, since there is no power greater than God and we will be rewarded in the hereafter—then they would not have bothered us.”

Imam Khomeini’s point is that Islam cannot be reduced to a ritualistic or moralistic matter devoid of political essence. It is precisely Islam’s political articulation that prevents its dissolution.

The Islamism of the Islamic Republic

One of the fundamental differences expressed by Iranian Islamism, in contrast to other regional Islamization projects, is that Islam cannot be reduced to a fixed and limited set of characteristics. This idea is reflected in several letters that Imam Khomeini addressed to the then-president and current Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei. In these writings, Imam Khomeini asserts that the Islamic Republic can modify or even repeal any concrete manifestation of Islam if necessary to ensure its survival. While some experts interpret this stance as an expression of Imam Khomeini’s nationalist thinking, others see it as the affirmation of an Islam that transcends its historical manifestations and is always projected beyond them.

Another characteristic of Khomeinism is that, although Imam Khomeini considered himself a follower of Shia Islam, his political practice is understood as an attempt to bring Sunni and Shia closer together under what experts call a “post-mazhabi” vision—mazhab or madhhab meaning “legal school” in Arabic. This search for Islamic unity is key to understanding the Islamic Republic’s self-definition as a political home for all Muslims, positioning itself as a power capable of defending the entire Islamic community against Western aggression.

A final fundamental pillar of Khomeinism is the doctrine of Wilayat al-faqih, translated as “government of the jurist,” which represents the most important political vision of this current. Imam Khomeini understood that the solution to the problems of Iran and the Islamic community in general is not merely theological but a political challenge requiring concrete responses in that sphere.

In fact, Imam Khomeini succeeded in creating an Islamic political identity capable of transcending national and sectarian divisions. His proposal conceives political agency as the capacity of Muslims to decolonize themselves and reweave their societies within an Islamic historical tradition. This decolonization aims at dismantling the global colonial order.

Therefore, for his followers, Imam Khomeini’s importance lies in his ability to break the identification between “universal” and “the West.” In other words, thanks to Khomeinism, the West is revealed as just another particularism within the global political world.

The experiment of the Islamic Revolution offered a unique opportunity for a mobilized Muslim subjectivity to construct a political order virtually ex nihilo. This revolution marked a profound rupture with modern hegemony, the paradigm of Westernesse, and the nation-state and ethnonational identity-based politics. The idea of the Islamic Republic was grounded in the mobilization of political subjects not around ethnic, linguistic, or national categories, but around a shared identity as Muslims. This politicization of Islam was precisely the discourse that Westernesse—with its strong drive toward secularization and cultural homogenization—sought to suppress and confine to the private sphere.

Imam Khomeini, however, was not merely the symbol of the revolution, but also the most powerful advocate of a political vision of Islam that rejected the role assigned to it by the machinery of modernity. His figure represents a deep and radical critique of that machinery. This critique was not limited to a literal or occasional refutation of Westernesse’s assumptions, but embodied the projection of a radically different future—one that overflowed the categories imposed by the hegemonic center of modern power.

Leave a Comment