The path to American authoritarianism

What comes after Democratic breakdown

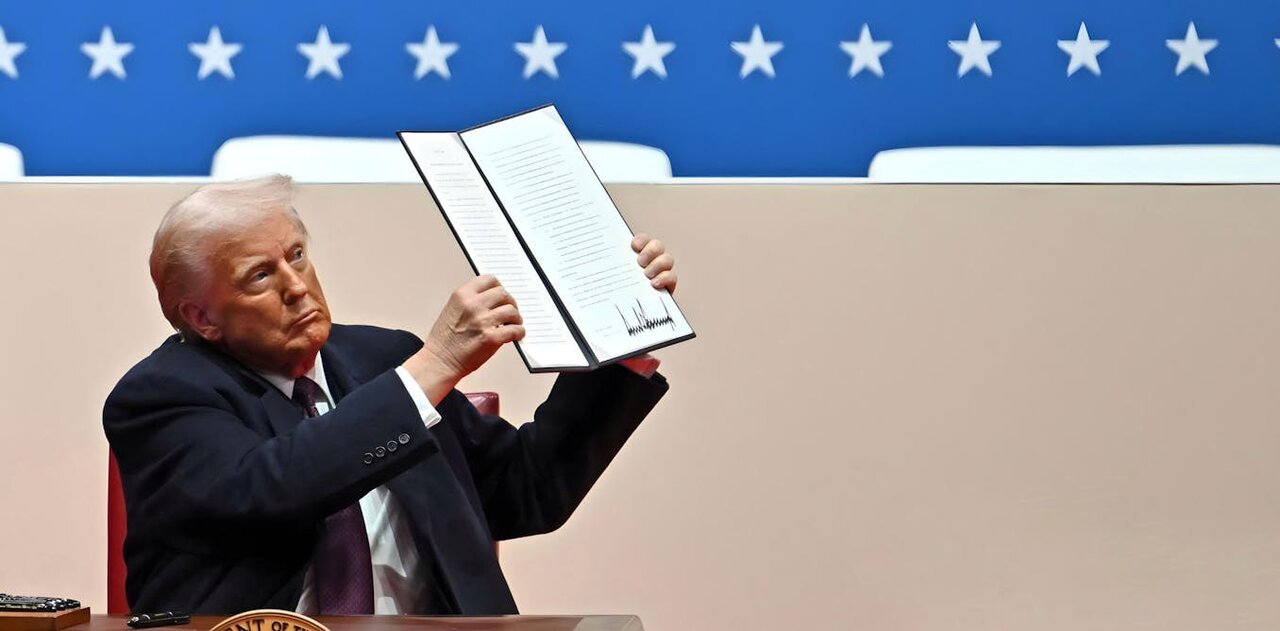

Donald Trump’s first election to the presidency in 2016 triggered an energetic defense of democracy from the American establishment. But his return to office has been met with striking indifference. Many of the politicians, pundits, media figures, and business leaders who viewed Trump as a threat to democracy eight years ago now treat those concerns as overblown—after all, democracy survived his first stint in office. In 2025, worrying about the fate of American democracy has become almost passé.

The timing of this mood shift could not be worse, for democracy is in greater peril today than at any time in modern U.S. history. America has been backsliding for a decade: between 2014 and 2021, Freedom House’s annual global freedom index, which scores all countries on a scale of zero to 100, downgraded the United States from 92 (tied with France) to 83 (below Argentina and tied with Panama and Romania), where it remains.

The country’s vaunted constitutional checks are failing. Trump violated the cardinal rule of democracy when he attempted to overturn the results of an election and block a peaceful transfer of power. Yet neither Congress nor the judiciary held him accountable, and the Republican Party—coup attempt notwithstanding—renominated him for president. Trump ran an openly authoritarian campaign in 2024, pledging to prosecute his rivals, punish critical media, and deploy the army to repress protest. He won, and thanks to an extraordinary Supreme Court decision, he will enjoy broad presidential immunity during his second term.

Democracy survived Trump’s first term because he had no experience, plan, or team. He did not control the Republican Party when he took office in 2017, and most Republican leaders were still committed to democratic rules of the game. Trump governed with establishment Republicans and technocrats, and they largely constrained him. None of those things are true anymore. This time, Trump has made it clear that he intends to govern with loyalists. He now dominates the Republican Party, which, purged of its anti-Trump forces, now acquiesces to his authoritarian behavior.

U.S. democracy will likely break down during the second Trump administration, in the sense that it will cease to meet standard criteria for liberal democracy: full adult suffrage, free and fair elections, and broad protection of civil liberties.

The breakdown of democracy in the United States will not give rise to a classic dictatorship in which elections are a sham and the opposition is locked up, exiled, or killed. Even in a worst-case scenario, Trump will not be able to rewrite the Constitution or overturn the constitutional order. He will be constrained by independent judges, federalism, the country’s professionalized military, and high barriers to constitutional reform. There will be elections in 2028, and Republicans could lose them.

But authoritarianism does not require the destruction of the constitutional order. What lies ahead is not fascist or single-party dictatorship but competitive authoritarianism—a system in which parties compete in elections but the incumbent’s abuse of power tilts the playing field against the opposition. Most autocracies that have emerged since the end of the Cold War fall into this category, including Alberto Fujimori’s Peru, Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela, and contemporary El Salvador, Hungary, India, Tunisia, and Turkey. Under competitive authoritarianism, the formal architecture of democracy, including multiparty elections, remains intact. Opposition forces are legal and above ground, and they contest seriously for power. Elections are often fiercely contested battles in which incumbents have to sweat it out. And once in a while, incumbents lose, as they did in Malaysia in 2018 and in Poland in 2023. But the system is not democratic, because incumbents rig the game by deploying the machinery of government to attack opponents and co-opt critics. Competition is real but unfair.

Competitive authoritarianism will transform political life in the United States. As Trump’s early flurry of dubiously constitutional executive orders made clear, the cost of public opposition will rise considerably: Democratic Party donors may be targeted by the IRS; businesses that fund civil rights groups may face heightened tax and legal scrutiny or find their ventures stymied by regulators. Critical media outlets will likely confront costly defamation suits or other legal actions as well as retaliatory policies against their parent companies. Americans will still be able to oppose the government, but opposition will be harder and riskier, leading many elites and citizens to decide that the fight is not worth it. A failure to resist, however, could pave the way for authoritarian entrenchment—with grave and enduring consequences for global democracy.

The weaponized state

The second Trump administration may violate basic civil liberties in ways that unambiguously subvert democracy. The president, for example, could order the army to shoot protesters, as he reportedly wanted to do during his first term. He could also fulfill his campaign promise to launch the “largest deportation operation in American history,” targeting millions of people in an abuse-ridden process that would inevitably lead to the mistaken detention of thousands of U.S. citizens.

But much of the coming authoritarianism will take a less visible form: the politicization and weaponization of government bureaucracy. Modern states are powerful entities. The U.S. federal government employs over two million people and has an annual budget of nearly $7 trillion. Government officials serve as important arbiters of political, economic, and social life. They help determine who gets prosecuted for crimes, whose taxes are audited, when and how rules and regulations are enforced, which organizations receive tax-exempt status, which private agencies get contracts to accredit universities, and which companies obtain critical licenses, concessions, contracts, subsidies, tariff waivers, and bailouts. Even in countries such as the United States that have relatively small, laissez-faire governments, this authority creates a plethora of opportunities for leaders to reward allies and punish opponents. No democracy is entirely free of such politicization. But when governments weaponize the state by using its power to systematically disadvantage and weaken the opposition, they undermine liberal democracy. Politics becomes like a soccer match in which the referees, the groundskeepers, and the scorekeepers work for one team to sabotage its rival.

This is why all established democracies have elaborate sets of laws, rules, and norms to prevent the state’s weaponization. These include independent judiciaries, central banks, and election authorities and civil services with employment protections. In the United States, the 1883 Pendleton Act created a professionalized civil service in which hiring is based on merit. Federal workers are barred from participating in political campaigns and cannot be fired or demoted for political reasons. The vast majority of the over two million federal employees have long enjoyed civil service protection. At the start of Trump’s second term, only about 4,000 of these were political appointees.

America is heading toward competitive authoritarian rule, not single-party dictatorship.The United States has also developed an extensive set of rules and norms to prevent the politicization of key state institutions. These include the Senate’s confirmation of presidential appointees, lifetime tenure for Supreme Court justices, tenure security for the chair of the Federal Reserve, ten-year terms for FBI directors, and five-year terms for IRS directors. The armed forces are protected from politicization by what the legal scholar Zachary Price describes as “an unusually thick overlay of statutes” governing the appointment, promotion, and removal of military officers. Although the Justice Department, the FBI, and the IRS remained somewhat politicized through the 1970s, a series of post-Watergate reforms effectively ended partisan weaponization of these institutions.

Professional civil servants often play a critical role in resisting government efforts to weaponize state agencies. They have served as democracy’s frontline of defense in recent years in Brazil, India, Israel, Mexico, and Poland, as well as in the United States during the first Trump administration. For this reason, one of the first moves undertaken by elected autocrats such as Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, Chávez in Venezuela, Viktor Orban in Hungary, Narendra Modi in India, and Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey has been to purge professional civil servants from public agencies responsible for things such as investigating and prosecuting wrongdoing, regulating the media and the economy, and overseeing elections—and replace them with loyalists. After Orban became prime minister in 2010, his government stripped public employees of key civil service protections, fired thousands, and replaced them with loyal members of the ruling Fidesz party. Likewise, Poland’s Law and Justice party weakened civil service laws by doing away with the competitive hiring process and filling the bureaucracy, the judiciary, and the military with partisan allies.

Trump and his allies have similar plans. For one, Trump has revived his first-term effort to weaken the civil service by reinstating Schedule F, an executive order that allows the president to exempt tens of thousands of government employees from civil service protections in jobs deemed to be “of a confidential, policy-determining, policy-making, or policy-advocating character.” If implemented, the decree will transform tens of thousands of civil servants into “at will” employees who can easily be replaced with political allies. The number of partisan appointees, already higher in the U.S. government than in most established democracies, could increase more than tenfold. The Heritage Foundation and other right-wing groups have spent millions of dollars recruiting and vetting an army of up to 54,000 loyalists to fill government positions. These changes could have a broader chilling effect across the government, discouraging public officials from questioning the president. Finally, Trump’s declaration that he would fire the director of the FBI, Christopher Wray, and the director of the IRS, Danny Werfel, before the end of their terms led both to resign, paving the way for their replacement by loyalists with little experience in their respective agencies.

Once key agencies such as the Justice Department, the FBI, and the IRS have been packed with loyalists, governments can harness them for three antidemocratic ends: investigating and prosecuting rivals, co-opting civil society, and shielding allies from prosecution.

Shock and law

The most visible means of weaponizing the state is through targeted prosecution. Virtually all elected autocratic governments deploy justice ministries, public prosecutors’ offices, and tax and intelligence agencies to investigate and prosecute rival politicians, media companies, editors, journalists, business leaders, universities, and other critics. In traditional dictatorships, critics are often charged with crimes such as sedition, treason, or plotting insurrection, but contemporary autocrats tend to prosecute critics for more mundane offenses, such as corruption, tax evasion, defamation, and even minor violations of arcane rules. If investigators look hard enough, they can usually find petty infractions such as unreported income on tax returns or noncompliance with rarely enforced regulations.

Trump has repeatedly declared his intention to prosecute his rivals, including former Republican Representative Liz Cheney and other lawmakers who served on the House committee that investigated the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. In December 2024, House Republicans called for an FBI investigation into Cheney. The first Trump administration’s efforts to weaponize the Justice Department were largely thwarted from within, so this time, Trump sought appointees who shared his goal of pursuing perceived enemies. His nominee for attorney general, Pam Bondi, has declared that Trump’s “prosecutors will be prosecuted,” and his choice for FBI director, Kash Patel, has repeatedly called for the prosecution of Trump’s rivals. In 2023, Patel even published a book featuring an “enemies list” of public officials to be targeted.

Because the Trump administration will not control the courts, most targets of selective prosecution will not end up in prison. But the government need not jail its critics to inflict harm on them. Targets of investigation will be forced to devote considerable time, energy, and resources to defending themselves; they will spend their savings on lawyers, their lives will be disrupted, their professional careers will be sidetracked, and their reputations will be damaged. At a minimum, they and their families will suffer months or years of anxiety and sleepless nights.

Trump’s efforts to use government agencies to harass his perceived adversaries will not be limited to the Justice Department and the FBI. A variety of other departments and agencies can be deployed against critics. Autocratic governments, for example, routinely use tax authorities to target opponents for politically motivated investigations. In Turkey, the Erdogan government gutted the Dogan Yayin media group, whose newspapers and TV networks were reporting on government corruption, by charging it with tax evasion and imposing a crippling $2.5 billion fine that forced the Dogan family to sell its media empire to government cronies. Erdogan also used tax audits to pressure the Koc Group, Turkey’s largest industrial conglomerate, to abandon its support for opposition parties.

The Trump administration could similarly deploy the tax authorities against critics. The Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations all politicized the IRS before the 1970s Watergate scandal led to reforms. An influx of political appointees would weaken those safeguards, potentially leaving Democratic donors in the cross hairs. Because all individual campaign donations are publicly disclosed, it would be easy for the Trump administration to identify and target those donors; indeed, fear of such targeting could deter individuals from contributing to opposition politicians in the first place.

Tax-exempt status may also be politicized. As president, Richard Nixon worked to deny or delay tax-exempt status for organizations and think tanks he viewed as politically hostile. Under Trump, such efforts could be facilitated by antiterrorism legislation passed in November 2024 by the House of Representatives that empowers the Treasury Department to withdraw tax-exempt status from any organization it suspects of supporting terrorism without having to disclose evidence to justify such an act. Because “support for terrorism” can be defined very broadly, Trump could, in the words of Democratic Representative Lloyd Doggett, “use it as a sword against those he views as his political enemies.”

The Trump administration will almost certainly deploy the Department of Education against universities, which as centers of opposition activism are frequent targets of competitive authoritarian governments’ ire. The Department of Education hands out billions of dollars in federal funding for universities, oversees the agencies responsible for college accreditation, and enforces compliance with Title VI and Title IX, laws that prohibit educational institutions from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, or sex. These capacities have rarely been politicized in the past, but Republican leaders have called for their deployment against elite schools.

Elected autocrats also routinely use defamation suits and other forms of legal action to silence their critics in the media. In Ecuador in 2011, for example, President Rafael Correa won a $40 million lawsuit against a columnist and three executives at a leading newspaper for publishing an editorial calling him a “dictator.”

Although public figures rarely win such suits in the United States, Trump has made ample use of a variety of legal actions to wear down media outlets, targeting ABC News, CBS News, The Des Moines Register, and Simon & Schuster. His strategy has already borne fruit. In December 2024, ABC made the shocking decision to settle a defamation suit brought by Trump, paying him $15 million to avoid a trial in which it probably would have prevailed. The owners of CBS are also reportedly considering settling a lawsuit by Trump, showing how spurious legal actions can prove politically effective.

The administration need not directly target all its critics to silence most dissent. Launching a few high-profile attacks may serve as an effective deterrent. A legal action against Cheney would be closely watched by other politicians; a suit against The New York Times or Harvard would have a chilling effect on dozens of other media outlets or universities.

Honey trap

A weaponized state is not merely a tool to punish opponents. It can also be used to build support. Governments in competitive authoritarian regimes routinely use economic policy and regulatory decisions to reward politically friendly individuals, firms, and organizations. Business leaders, media companies, universities, and other organizations have as much to gain as they have to lose from government antitrust decisions, the issuing of permits and licenses, the awarding of government contracts and concessions, the waiving of regulations or tariffs, and the conferral of tax-exempt status. If they believe that these decisions are made on political rather than technical grounds, they have a strong incentive to align themselves with incumbents.

The potential for co-optation is clearest in the business sector. Major American companies have much at stake in the U.S. government’s antitrust, tariff, and regulatory decisions and in the awarding of government contracts. (In 2023, the federal government spent more than $750 billion, or nearly three percent of the United States’ GDP, on awarding contracts.) For aspiring autocrats, policy and regulatory decisions can serve as powerful carrots and sticks to attract business support. This kind of patrimonial logic helped autocrats in Hungary, Russia, and Turkey secure private-sector cooperation. If Trump sends credible signals that he will behave in a similar manner, the political consequences will be far-reaching. If business leaders become convinced that it is more profitable to avoid financing opposition candidates or investing in independent media, they will change their behavior.

Indeed, their behavior has already begun to change. In what the New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg termed “the Great Capitulation,” powerful CEOs who had once criticized Trump’s authoritarian behavior are now rushing to meet with him, praise him, and give him money. Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Toyota each gave $1 million to fund Trump’s inauguration, more than double their previous inaugural donations. In early January, Meta announced it was abandoning its fact-checking operations—a move that Trump bragged “probably” resulted from his threats to take legal action against Meta’s owner, Mark Zuckerberg. Trump himself has recognized that in his first term, “everyone was fighting me,” but now “everybody wants to be my friend.”

A similar pattern is emerging in the media sector. Nearly all major U.S. media outlets—ABC, CBS, CNN, NBC, The Washington Post—are owned and operated by larger parent corporations. Although Trump cannot carry out his threat to withhold licenses from national television networks because they are not licensed nationally, he can pressure media outlets by pressuring their corporate owners. The Washington Post, for instance, is controlled by Jeff Bezos, whose largest company, Amazon, competes for major federal contracts. Likewise, the owner of The Los Angeles Times, Patrick Soon-Shiong, sells medical products subject to review by the Food and Drug Administration. Ahead of the 2024 presidential election, both men overruled their papers’ planned endorsements of Kamala Harris.

Protection racket

Finally, a weaponized state can serve as a legal shield to protect government officials or allies who engage in antidemocratic behavior. A loyalist Justice Department, for example, could turn a blind eye to acts of pro-Trump political violence, such as attacks on or threats against journalists, election officials, protesters, or opposition politicians and activists. It could also decline to investigate Trump supporters for efforts to intimidate voters or even manipulate the results of elections.

This has happened before in the United States. During and after Reconstruction, the Ku Klux Klan and other armed white supremacist groups with ties to the Democratic Party waged violent terror campaigns across the South, assassinating Black and Republican politicians, burning Black homes, businesses, and churches, committing election fraud, and threatening, beating, and killing Black citizens who attempted to vote. This wave of terror, which helped establish nearly a century of single-party rule across the South, was made possible by the collusion of state and local law enforcement authorities, who routinely turned a blind eye to the violence and systematically failed to hold its perpetrators accountable.

The United States experienced a marked rise in far-right violence during the first Trump administration. Threats against members of Congress increased more than tenfold. These threats had consequences: according to Republican Senator Mitt Romney, fear of Trump supporters’ violence dissuaded some Republican senators from voting for Trump’s impeachment after the January 6, 2021, attack.

By most measures, political violence subsided after January 2021, in part because hundreds of participants in the January 6 attack were convicted and imprisoned. But Trump’s pardon of nearly all the January 6 insurrectionists on returning to office has sent a message that violent or antidemocratic actors will be protected under his administration. Such signals encourage violent extremism, which means that during Trump’s second term, critics of the government and independent journalists will almost certainly face more frequent threats and even outright attacks.

Governments need not jail their critics to silence dissent.None of this would be entirely new for the United States. Presidents have weaponized government agencies before. The FBI director J. Edgar Hoover deployed the agency as a political weapon for the six presidents he served. The Nixon administration wielded the Justice Department and other agencies against perceived enemies. But the contemporary period differs in important ways. For one, global democratic standards have risen considerably. By any contemporary measure, the United States was considerably less democratic in the 1950s than it is today. A return to mid-twentieth-century practices would, by itself, constitute significant democratic backsliding.

More important, the coming weaponization of government will likely go well beyond mid-twentieth-century practices. Fifty years ago, both major U.S. parties were internally heterogeneous, relatively moderate, and broadly committed to democratic rules of the game. Today, these parties are far more polarized, and a radicalized Republican Party has abandoned its long-standing commitment to basic democratic rules, including accepting electoral defeat and unambiguously rejecting violence.

Moreover, much of the Republican Party now embraces the idea that America’s institutions—from the federal bureaucracy and public schools to the media and private universities—have been corrupted by left-wing ideologies. Authoritarian movements commonly embrace the notion that their country’s institutions have been subverted by enemies; autocratic leaders including Erdogan, Orban, and Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro routinely push such claims. Such a worldview tends to justify—even motivate—the kind of purging and packing that Trump promises. Whereas Nixon worked surreptitiously to weaponize the state and faced Republican opposition when that behavior came to light, today’s GOP now openly encourages such abuses. Weaponization of the state has become Republican strategy. The party that once embraced President Ronald Reagan’s campaign dictum that the government was the problem now enthusiastically embraces the government as a political weapon.

Using executive power in this way is what Republicans learned from Orban. Orban taught a generation of conservatives that the state should not be dismantled but rather wielded in pursuit of right-wing causes and against opponents. This is why tiny Hungary has become a model for so many Trump supporters. Weaponizing the state is not some new feature of conservative philosophy—it is an age-old feature of authoritarianism.

Natural immunity?

The Trump administration may derail democracy, but it is unlikely to consolidate authoritarian rule. The United States possesses several potential sources of resilience. For one, American institutions are stronger than those in Hungary, Turkey, and other countries with competitive authoritarian regimes. An independent judiciary, federalism, bicameralism, and midterm elections—all absent in Hungary, for instance—will likely limit the scope of Trump’s authoritarianism.

Trump is also weaker politically than many successful elected autocrats. Authoritarian leaders do the most damage when they enjoy broad public support: Bukele, Chávez, Fujimori, and Russia’s Vladimir Putin all boasted approval ratings above 80 percent when they launched authoritarian power grabs. Such overwhelming public support helps leaders secure the legislative supermajorities or landslide plebiscite victories needed to impose reforms that entrench autocratic rule. It also helps deter challenges from intraparty rivals, judges, and even much of the opposition.

Less popular leaders, by contrast, face greater resistance from legislatures, courts, civil society, and even their own allies. Their power grabs are thus more likely to fail. Peruvian President Pedro Castillo and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol each had approval ratings below 30 percent when they attempted to seize extraconstitutional power, and both failed. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s approval rating was well below 50 percent when he tried to orchestrate a coup to overturn his country’s 2022 presidential election. He, too, was defeated and forced out of office.

*The U.S. Constitution alone cannot save American democracy.Trump’s approval rating never surpassed 50 percent during his first term, and a combination of incompetence, overreach, unpopular policies, and partisan polarization will likely limit his support during his second. An elected autocrat with a 45 percent approval rating is dangerous, but less dangerous than one with 80 percent support.

Civil society is another potential source of democratic resilience. One major reason that rich democracies are more stable is that capitalist development disperses human, financial, and organizational resources away from the state, generating countervailing power in society. Wealth cannot wholly inoculate the private sector from the pressures imposed by a weaponized state. But the larger and richer a private sector is, the harder it is to fully capture or bully into submission. In addition, wealthier citizens have more time, skills, and resources to join or create civic or opposition organizations, and because they depend less on the state for their livelihoods than poor citizens do, they are in a better position to protest or vote against the government. Compared with those in other competitive authoritarian regimes, opposition forces in the United States are well-organized, well-financed, and electorally viable, which makes them harder to co-opt, repress, and defeat at the polls. American opposition will therefore be harder to sideline than it was in countries such as El Salvador, Hungary, and Turkey.

Chinks in the armor

But even a modest tilting of the playing field could cripple American democracy. Democracies require robust opposition, and robust oppositions must be able to draw on a large and replenishable pool of politicians, activists, lawyers, experts, donors, and journalists.

A weaponized state imperils such opposition. Although Trump’s critics won’t be jailed, exiled, or banned from politics, the heightened cost of public opposition will lead many of them to retreat to the political sidelines. In the face of FBI investigations, tax audits, congressional hearings, lawsuits, online harassment, or the prospect of losing business opportunities, many people who would normally oppose the government may conclude that it simply is not worth the risk or effort.

This process of self-sidelining may not attract much public attention, but it can be highly consequential. Facing looming investigations, promising politicians—Republicans and Democrats alike—leave public life. CEOs seeking government contracts, tariff waivers, or favorable antitrust rulings stop contributing to Democratic candidates, funding civil rights or democracy initiatives, and investing in independent media. News outlets whose owners worry about lawsuits or government harassment rein in their investigative teams and their most aggressive reporters. Editors engage in self-censorship, softening headlines and opting not to run stories critical of the government. And university leaders fearing government investigations, funding cuts, or punitive endowment taxes crack down on campus protest, remove or demote outspoken professors, and remain silent in the face of growing authoritarianism.

Weaponized states create a difficult collective action problem for establishment elites who, in theory, would prefer democracy to competitive authoritarianism. The politicians, CEOs, media owners, and university presidents who modify their behavior in the face of authoritarian threats are acting rationally, doing what they deem best for their organizations by protecting shareholders or avoiding debilitating lawsuits, tariffs, or taxes. But such acts of self-preservation have a collective cost. As individual actors retreat to the sidelines or censor themselves, societal opposition weakens. The media environment grows less critical. And pressure on the authoritarian government diminishes.

The depletion of societal opposition may be worse than it appears. We can observe when key players sideline themselves—when politicians retire, university presidents resign, or media outlets change their programming and personnel. But it is harder to see the opposition that might have materialized in a less threatening environment but never did—the young lawyers who decide not to run for office; the aspiring young writers who decide not to become journalists; the potential whistleblowers who decide not to speak out; the countless citizens who decide not to join a protest or volunteer for a campaign.

Hold the line

America is on the cusp of competitive authoritarianism. The Trump administration has already begun to weaponize state institutions and deploy them against opponents. The Constitution alone cannot save U.S. democracy. Even the best-designed constitutions have ambiguities and gaps that can be exploited for antidemocratic ends. After all, the same constitutional order that undergirds America’s contemporary liberal democracy permitted nearly a century of authoritarianism in the Jim Crow South, the mass internment of Japanese Americans, and McCarthyism. In 2025, the United States is governed nationally by a party with greater will and power to exploit constitutional and legal ambiguities for authoritarian ends than at any time in the past two centuries.

Trump will be vulnerable. The administration’s limited public support and inevitable mistakes will create opportunities for democratic forces—in Congress, in courtrooms, and at the ballot box.

But the opposition can win only if it stays in the game. Opposition under competitive authoritarianism can be grueling. Worn down by harassment and threats, many of Trump’s critics will be tempted to retreat to the sidelines. Such a retreat would be perilous. When fear, exhaustion, or resignation crowds out citizens’ commitment to democracy, emergent authoritarianism begins to take root.

Teven Levitsky is David Rockefeller professor of Latin American Studies and professor of government at Harvard University and a senior fellow for Democracy at the Council on Foreign Relations.

LUCAN A. Way is distinguished professor of pemocracy in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto and a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

They are the authors of Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War.

(Source: Foreign Affairs)

Leave a Comment