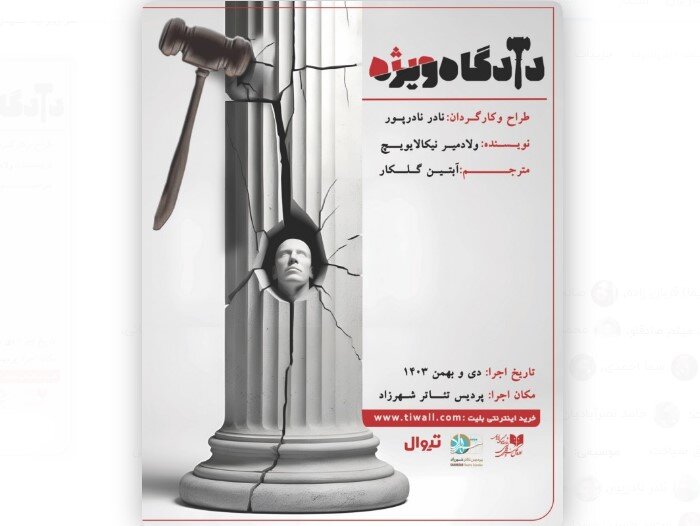

Adaptation of Voinovich’s “Tribunal” on stage in Tehran

TEHRAN- An adaptation of Russian writer Vladimir Voinovich’s play “Tribunal: A Courtly Comedy in Three Acts” is currently on stage at Shahrzad Theater Complex in Tehran.

Nader Naderpour is the director of the play, which has been translated into Persian by prominent Iranian translator Abtin Golkar.

Alireza Qorbanzadeh, Saleheh Dorani, Armin Hemmati, Sama Ahmadi and Aida Moradi are the main members of the cast for the play, which will remain on stage until February 8.

“Tribunal: A Courtly Comedy in Three Acts” serves as a biting satire of the 1960s and 1970s Soviet show trials, reflecting the experiences of one of the Soviet Union's most notable dissidents.

Voinovich, often hailed as 20th Century Russia’s "greatest living satirist," drew inspiration from his reactions to the Sinyavski/Daniel trial in 1966, an event that incited him to launch a series of scathing letters directed at Premier Leonid Brezhnev and the Soviet Writers' Union. This passionate engagement ultimately led to his expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1981.

“Tribunal,” therefore, stands not merely as a comedic work but as a tribute to the brave souls who resisted Soviet oppression during the Cold War, while simultaneously critiquing the broader cultural censorship faced by dissident writers globally.

In the tradition of the theatre of the absurd—mirroring the styles of luminaries like Aristophanes, Sartre, Frisch, and Havel—Voinovich constructs a narrative that is both darkly humorous and outrageously absurd.

The play unfolds as Senya and Larissa Suspectnikoff, oblivious to the theater's true nature, enter what they believe to be a Chekhovian comedy. Instead, they find themselves entangled in the farcical and sinister workings of a Soviet criminal tribunal. The stage is set with eerie reminders of a court setting: benches for the Prosecutor and Public Defender, and even a cage for the Defendant, while Themis, the Goddess of Justice, awkwardly balances the hammer and sickle against a Kalashnikov.

The atmosphere quickly shifts as ominous sounds echo from outside—siren wails and the blaring lights of police vehicles create a palpable sense of dread.

When the Tribunal Members swagger onto the stage in a theatrically exaggerated manner, the audience realizes they are trapped in a grotesque mock trial. Security forces, armed and vigilant, block the exits, effectively rendering the spectators captives in this surreal performance.

Voinovich ingeniously collapses the barrier between reality and fiction, immersing the audience in the psychological turmoil that defined the Soviet experience during Brezhnev's stagnation.

As the initial discomfort settles in, Larissa voices her growing confusion, questioning the presence of armed guards. Senya, attempting to reassure her, dismisses her fears as mere theatrics. Unbeknownst to them, their questioning will lead to their unwelcome roles as defendants in this farcical trial. The Chairman's assertion, "Where there’s a show-trial, we need somebody to try!" epitomizes the absurdity of the proceedings.

Despite Senya's claims of innocence, the tribunal remains indifferent, and by the end of Act I, he finds himself caged, while Larissa stands helplessly by, torn between belief in her husband's guilt or innocence.

As the comedy unfolds, Voinovich navigates the tenuous balance between humor and tragedy, exploring themes of personal and political identity. Eventually, Senya transforms into a global dissident figure, inciting advocacy and protests in Western democracies.

Yet the play poses critical questions: Is he a hero or simply a pawn in a larger geopolitical game, forced to conform to the caricature of a "Soviet dissident"? The final act leaves these questions unresolved as Senya is taken offstage, prompting the audience to confront the complexities of truth and representation in a world rife with absurdity and oppression.

Voinovich's masterful work thus encapsulates the essence of dissent in the face of an unforgiving regime, leaving a resonating impact on audiences both within and beyond the Soviet sphere.

SAB/

Leave a Comment