Special Exhibition at National Museum celebrates Muharram symbols

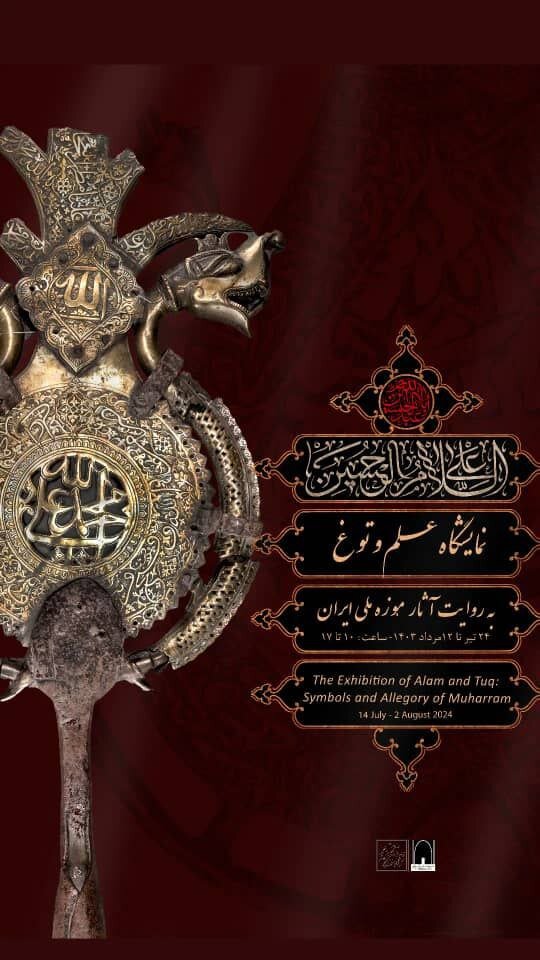

TEHRAN- The National Museum of Iran has unveiled the exhibition, “Alam and Tuq: Symbols and Allegory of Muharram,” in honor of the Imam Hussain (AS), the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), which was martyred on the tenth day of the lunar month in 680 CE.

The event, according to organizers, offers a profound glimpse into two of the time-honored religious elements being used by Shia Muslims Islamic in rituals integral to Muharram commemorations.

The exhibition was inaugurated on Sunday by Jabrael Nokandeh, the general director of the museum, who emphasized the importance of preserving and showcasing these historical artifacts. “This exhibition not only honors the memory of Imam Hussain (AS) but also serves as a testament to the enduring cultural and religious practices that have shaped our history,” Nokandeh remarked.

The display includes 14 meticulously restored objects from the Safavid and Qajar periods, highlights the craftsmanship and religious significance of the era, the offical added.

Among the objects on view are the Tuqs, flag heads, and steel fruits—elements deeply embedded in the Muharram ceremonies. These items, crafted from brass, bronze, and steel, are being exhibited for the first time post-restoration. Particularly noteworthy are the steel fruits, including quince and bergamot oranges, which are adorned with intricate gilding motifs and inscriptions, symbolizing the rich artistic heritage of the periods they represent.

The Alams, also known as processional standards, are central to the Shia Muslim community's commemorations of the martyrdom of Imam Hussain (AS) and his loyal companions in the Battle of Karbala.

These standards are carried in processions, embodying the spirit of mourning and remembrance that characterizes Muharram. The exhibition's Tuqs, originally used in battlefields, have evolved into ritualistic symbols, deeply rooted in the cultural fabric of Iran, especially since the 7th century AH during the Ilkhanate period. Back then, Tuqs served as ritual accessories for Javanmardan, or chivalrous individuals, with each Khaneghah (Sufi lodge) having its own distinctive “Patuq” sign.

During the Safavid era, Tuqs attained greater prominence, adorned with inscriptions of Quranic verses, the names of God and the Imams, blessings, prayers, dedications, and construction dates. The designs from this period also incorporated dragons and snakes, as seen in surviving miniatures, adding a unique artistic element to these ritual objects. The Iranian Tuqs are particularly notable for their two dragon or snake heads, which cover the upper part of the Tuq, evolving into what is known as “Alamat” or “Alam” banners. These banners often feature metal sculptures of animals and fruits placed between sharp blades.

The Qajar period saw an expansion in the use and ritual significance of Tuqs. “Patuq” became synonymous with neighborhoods, and carrying Tuqs during Muharram was a privilege of the Patuqdar, who led the mourning activities. This tradition of neighborhood-based mourning groups continues to be a vital part of Muharram commemorations throughout Iran.

The exhibition, housed in the temporary exhibition hall of the Museum of Islamic Archeology and Art of Iran, offers visitors a unique opportunity to engage with these historical artifacts and understand their cultural and religious significance. Through this display, the National Museum of Iran not only preserves the memory of Imam Hussain (AS) but also fosters a deeper appreciation of the rich heritage and artistic traditions that continue to shape Iranian culture.

The exhibition is open to the public until August 2, providing a rare glimpse into the historical and cultural legacy of Muharram.

Chock-full of priceless objects showcasing the juicy history of the nation, the National Museum showcases ceramics, pottery, stone figures, and carvings, mostly taken from excavations at Persepolis, Ismail Abad (near Qazvin), Shush, Rey, and Turang Tappeh to name a few. Inside, among the finds from Shush, there’s a stone capital of a winged lion, some delightful pitchers and vessels in animal shapes, and colorful glazed bricks decorated with double-winged mythical creatures. A copy of the diorite stele detailing the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, found at Shush in 1901, is also displayed – the original being in Paris.

AM

Leave a Comment