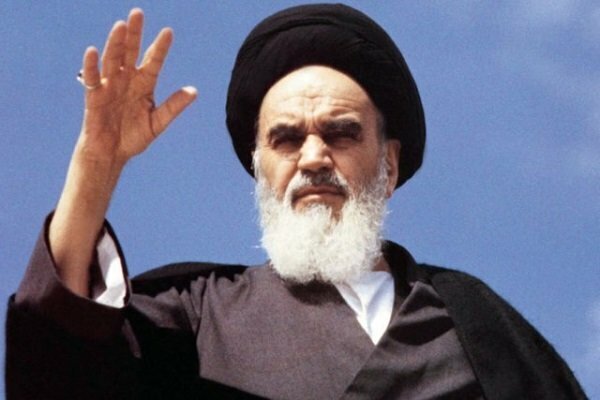

Imam Khomeini’s Legacy: A viable and resilient model of Islamic governance

“Whatever one’s opinion of [Imam] Khomeini, it is difficult to deny that he was one of the most astute theo-political leaders in modern history.” —Amin Saikal, Professor of Political Science at the Australian National University [1]

It is safe to say that without Imam Khomeini, there would be no Islamic Republic of Iran today. But the ideological earthquake triggered by this charismatic Islamic leader during his lifetime sent tremors well beyond the borders of Iran and the Persian Gulf region, and continues to propagate aftershocks globally to this very day, decades after his heavenly departure on the 13th of the Persian month of Khordad in the year 1368 SH, corresponding to June 3, 1989.

Born on the 30th of Shahrivar in the year 1281, September 24, 1902, in the central Iranian town of Khomein, the young Ruhollah Mousavi experienced the pain of being orphaned at the age of five months when his father, Ayatollah Mostafa Mousavi, was martyred while travelling from Khomein to Arak. By the age of 15, the young future founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran had also lost his mother, Banu Hajar, and his aunt, Sahebeh Khanom. In the year 1300 SH / 1921 CE, the young Khomeini migrated to Qom to study at the Theological Assembly, where he completed his “Level” studies with the late Ayatollah Seyyed Mohammad Taqi Khonsari and the late Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Yathrebi Kashani. By the time Grand Ayatollah Borujerdi came to Qom, Imam Khomeini was already a recognized teacher with authority in the areas of jurisprudence (feqh), philosophy (hekmat) and mysticism (erfan.) [2]

The tenth of the Islamic month of Muharram is the most somber day of the year for Shi’a Muslims, being the day in the year 61 AH / 18 Mehr 59 SH / October 10, 680 CE that Imam Hussein was martyred on the plains near Karbala, Iraq along with 72 of his close companions by the forces of the tyrannical Umayyad caliph, Yazid ibn Muawiyah. [3] On that very day some 1300 years later, Imam Khomeini gave a speech at the Feyziyeh School in Qom denouncing the shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, for his attempts at eradicating Islam and the religious scholars (ulama) from Iranian society, and warning him, “I don’t want to see the people be thankful for your departure if some day they make you leave.” [4]

At 3 am on the 15th of Khordad, 1342 / June 5, 1963, the shah’s commandos arrested the Imam and took him to Tehran, where he was imprisoned first at Qasr and then at Eshratabad Military Base until being released almost a year later. Upon the first anniversary of his arrest, and the subsequent protests, which became known as the 15th of Khordad uprising and were brutally suppressed, the Imam called for a general day of mourning. Months later, he gave another address, this time condemning the shah’s benefactor, the United States of America in no uncertain terms. “Let the world know that all the troubles that the Iranian nation and the Muslim nations have are from the U.S.,” he declared, “The Islamic nations hate imperialism in general and the U.S. in particular ... It is the U.S. that empowers Israel to make Muslim Arabs homeless...” Once again, the Imam was arrested, but this time, he was flown to Ankara, Turkey on a military aircraft to begin an exile from his homeland, which did not end until his triumphant return 14 years later on 12 Bahman 1357 / February 1, 1979. [5]

While exiled in Najaf, Iraq, the Imam formulated his concept of Islamic governance (Hukumat-e Islami) in a series of lectures given at the seminary in 1971. In those sessions, the form of Islamic government known as Velayat-e Faqih, which could be translated as guardianship by the jurist, was refined by him based on the assumption of the necessity of political authority based firmly on Islamic law (shari’ah) but implemented through decentralized, local self-governance with the mosque as the central institution to allow public participation. Such a government would be “a catalyst and tool for igniting and promoting massive behavioral change, in order to bring about a just community ... to recover government for human interests,” and, obviously, present an ominous threat to the frivolous claims made by the west of the superiority of its form of alleged culture and civilization. [6]

On January 16, 1979, the shah fled Iran for what was to be another “temporary stay” elsewhere, like the trip he had made after the initially unsuccessful U.S.-British coup attempt on August 16, 1953, but this time there was no returning. Previously on December 29, the shah had appointed Shapour Bakhtiar as prime minister, ordering him to form a government, which was doomed from the onset. Rejecting the legitimacy of this desperation measure on the part of the shah, the Imam established a revolutionary council on January 12. Days after his arrival on February 1, the Imam organized a provisional Islamic government, and by 2 pm on February 11, the armed forces declared their neutrality, Bakhtiar fled to Paris, and the victory of the Islamic revolution was at hand. [7]

“The basic reason for the unique success of Iran’s Islamic revolution was [Imam] Khomeini’s charismatic authority,” wrote Henry L. Munson, Jr., Professor of Anthropology at the University of Maine. [8] But there was more at work here than mere charisma: the Imam fully understood the nature of the imperial power he was confronting, which consisted of the massive firepower of the shah’s U.S.-trained and equipped military. Therefore, in lieu of armed confrontation, his approach was to appeal to the soldiers in a simple but effective manner, asking them not to shoot and kill their unarmed civilian brothers and sisters who were protesting. As a result, the shah’s mighty military machine was immobilized in its tracks; the soldiers initially disobeyed orders to shoot, then began arresting the selfsame officers giving those orders, and, in the end, charged them with crimes against humanity. [9] “Whatever the exact number of casualties in the course of the Iranian Revolution,” writes Professor of Iranian Studies at Columbia University Hamid Dabashi, “there is little doubt that this was a historic confrontation between the power of the spoken word and the might of the loaded machine guns.” [10]

With the victory of the Islamic revolution, Imam Khomeini had actualized the words of Dr. Ali Shariati, who had prescribed the cure for the illness of the Iranian people under the U.S.-imposed shah as being a return to their authentic Shi’i Islamic identity. “Our people remember nothing from this distant past and do not care to learn about pre-Islamic civilizations,” he wrote, referring obliquely to the shah’s obsession with returning Iran to the glories of a mythical, pre-Islamic Persian past and relegating Islam and its ulama (clergy) to irrelevancy. “Consequently, for us to return to our roots means not a rediscovery of pre-Islamic Iran, but a return to our Islamic, especially Shi’i, roots.” [11]

Years earlier, the Iranian intellectual, author and social critic, Jalal Al-e Ahmad, had referred to this societal disease of blind adoration and imitation of everything and anything western as gharbzadegi, which can be translated variously as “weststruckness,” “westoxification,” or “infatuation with the west.” Rightly accusing the traditional, quietist ulama of serving the interests of the shah and the “westoxified” supporters of the regime by their silence, Dr. Shariati transformed the Shi’i concept of entezar, which had meant waiting passively with hopeful expectation for the reappearance of the 12th Imam of the Shi’a, Imam Mahdi (as), into meaning actively resisting, organizing and revolting against taghut (unjust and ungodly) rulers and governments in preparation for the Imam’s eventual return. [12]

Imam Khomeini fulfilled Dr. Shariati’s vision by leading a revolution that toppled the shah’s regime and established in its place a viable and resilient Islamic government in Iran, true to the Iranian peoples’ Shi’i roots and based on his concept of Nezam-e Mohammadi of pure Mohammedan Islam. A constitution incorporating Imam Khomeini’s principle of velayat-e faqih, which recognized the authority of a Supreme Leader as a guardian-ruler during the occultation of the 12th Imam, was drafted by a group of Islamic scholars in the summer of 1979 and approved by an overwhelming majority of the Iranian people in December of that year. [13]

Having proved its viability, Imam Khomeini’s concept of Islamic government as established in the Islamic Republic of Iran went on to prove its resilience in the face of a relentless onslaught of economic sanctions, propaganda campaigns and proxy wars all launched under the auspices of that shaytan-e bozorg, the United States of America and its partners in crime. Yet despite the best (or worst) efforts of this nation of warmongers, the Islamic Republic of Iran has endured as testimony to the lasting legacy of Imam Khomeini, decades after his heavenly departure in 1989. Furthermore, those who imagined that the Islamic revolution would pass away with the Imam were shocked to see that his death served to renew the revolutionary zeal of Islam-minded Iranians. [14]

Beyond establishing an Islamic government in Iran, Imam Khomeini initiated a seismic shift in geopolitical tectonics much to the horror of the U.S. and its clients. Reacting with a policy of dual containment, Washington allowed Saddam’s forces to invade from Iraq [15] and supported Wahhabi extremists in Afghanistan, but the result was ironic; U.S. forces were ensnared in ever-expanding, costly wars and open-ended military occupations to topple the very same regimes the Great Satan had incited against Iran. Moreover, this ill-conceived, imprudent U.S. policy only reinforced the Islamic Republic’s status as a rising power, thereby securing Imam Khomeini’s legacy of a viable, resilient Islamic form of governance for future generations of Iranians. [16]

Endnotes

1- Amin Saikal, Iran Rising (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), 62.

2 - Imam Khomeini’s Biography (Mashhad: Astan Quds Razavi, no date), 3, 5.

3 - Ibrahim Ayati, A Probe into the History of Ashura (Karachi: Islamic Seminary Publications, 1991), 108-109.

4 - Imam Khomeini’s Biography, ibid, 10.

5 - Ibid, 10-11, 16.

6 - Eric Walberg, Islamic Resistance to Imperialism (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2015), 56-58.

7 - Henry Munson, Jr., Islam and Revolution in the Middle East (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988), 63, 64.

8 - Ibid, 131.

9 - Walberg, ibid, 59.

10 - Hamid Dabashi, Theology of Discontent (New York and London: New York University Press, 1993), 419.

11 - John W. Limbert, Iran at War with History (London and New York: Routledge, 1987), 116, 117.

12 - Ibid, 117, 120.

13 - Ibid, 119-122.

14 - Farhang Rajaee, Islam and Modernism (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007), 152, 153.

15 - Chris Emery, “Reappraising the Carter Administration’s response to the Iran-Iraq War,” in The Iran-Iraq War, ed. Nigel Aston, Bruce Gibson (London and New York: Routledge, 2014), 150.

16 - Rajaee, ibid, 165, 166.

Leave a Comment