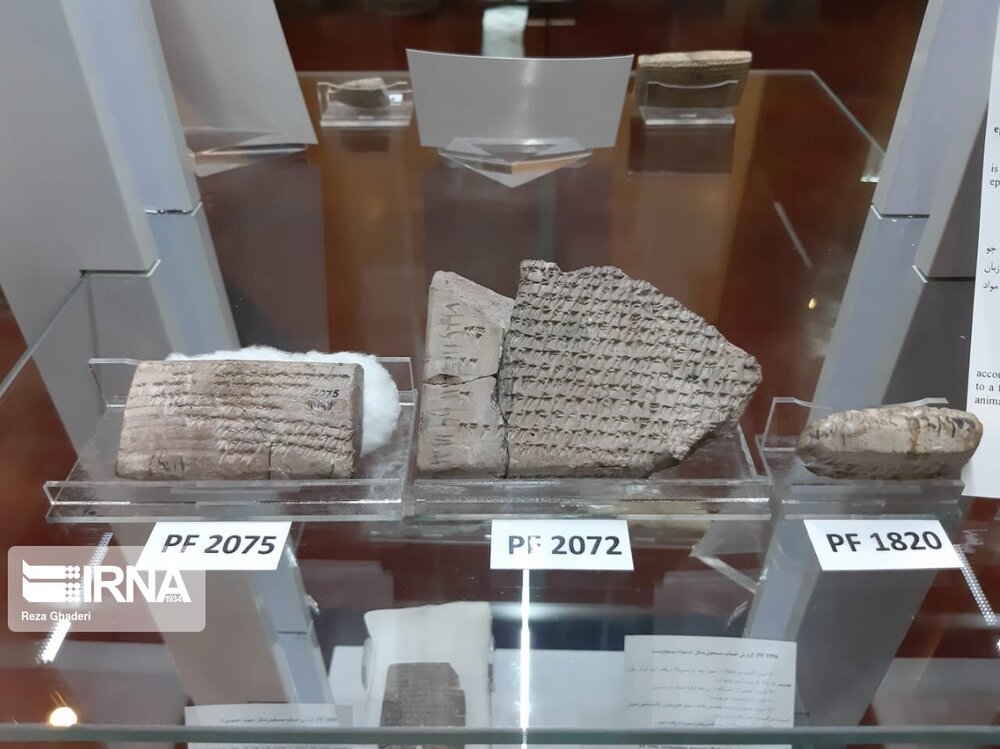

Achaemenid tablets returned to Persepolis for public show

TEHRAN – A selection of Achaemenid clay tablets, which were on loan from Iran to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago since 1935, has recently been put on show in the UNESCO-registered Persepolis.

The show named “Returning Home” was officially inaugurated on Sunday to commemorate Iran’s cultural heritage week, which comes to an end on May 24, IRNA reported.

“A selection of 110 (clay tablets), which can be categorized into 12 groups, have been transferred to Persepolis from the National Museum of Iran,” Fars province’s tourism chief said on Sunday.

“So far, more than 2,000 clay tablets have been returned home as the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts are trying its best to recover the rest,” Seyyed Moayyed Mohsennejad added.

In 2019, a total of 1,783 tablets were returned home from the Oriental Institute after 84 years.

“These treasured documents decipher an important segment of recorded history of Achaemenids during the reign of Darius I (Darius the Great who reigned from 522 to 486 BC),” said Jebrael Nokandeh, director of the National Museum of Iran.

In February 2018, following years of ups and downs, the fate of those ancient Persian artifacts was left in the hands of the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of Iran.

In addition, Majid Takht-Ravanchi, Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations, said in January that the United States must return all Achaemenid clay tablets without any exceptions and excuses.

Even though these tablets are part of the culture and history of Iran and belong to its people, the U.S. continually delays returning them, Takht-Ravanchi said.

“The Iranian request is clear”, he said, adding that they want their tablets to be returned home promptly and safely.

Last September, a study on the tablets that once belonged to the treasury archives of the Achaemenid Empire, revealed workers of the mighty kingdom were paid silver as the wage.

Conducted by Iranian archaeologist Soheli Delshad, the study investigated 33 clay tablets, the majority of which date back to the time of Darius I (Darius the Great), who was the third Persian King of Kings, reigning from 522 BC until he died in 486 BC. According to the archaeologist, 136 men who received the payments were described as masonry (and possibly plasterers).

In the 1930s, archaeologists affiliated with the University of Chicago discovered the tablets while excavating in Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Persian Empire. However, the institute has resumed work in collaboration with colleagues in Iran, and the return of the tablets is part of a broadening of contacts between scholars in the two countries, said Gil Stein, director of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago.

The tablets reveal an economic, social, and religious history of the Achaemenid Empire (550-330 BC) and the larger Near Eastern region in the fifth century BC.

Last September, a study on the tablets that once belonged to the treasury archives of the Achaemenid Empire, revealed workers of the mighty kingdom were paid silver as the wage.

Darius I, byname Darius the Great, (born 550 BC—died 486), king of Persia from 522 to 486 BC, one of the greatest rulers of the Achaemenid dynasty, who was noted for his administrative genius and his great building projects. Darius attempted several times to conquer Greece; his fleet was destroyed by a storm in 492, and the Athenians defeated his army at Marathon in 490.

The Achaemenid [Persian] Empire was the largest and most durable empire of its time. The empire stretched from Ethiopia, through Egypt, to Greece, to Anatolia (modern Turkey), Central Asia, and India.

The royal city of Persepolis ranks among the archaeological sites which have no equivalent, considering its unique architecture, urban planning, construction technology, and art. Persepolis, also known as Takht-e Jamshid, whose magnificent ruins rest at the foot of Kuh-e Rahmat (Mountain of Mercy) is situated 60 kilometers northeast of the city of Shiraz in Fars province.

The city was burnt by Alexander the Great in 330 BC apparently as revenge on the Persians because it seems the Persian King Xerxes had burnt the Greek City of Athens around 150 years earlier. The city’s immense terrace was begun about 518 BC by Darius the Great, the Achaemenid Empire’s king. On this terrace, successive kings erected a series of architecturally stunning palatial buildings, among them the massive Apadana palace and the Throne Hall (“Hundred-Column Hall”).

This 13-ha ensemble of majestic approaches, monumental stairways, throne rooms (Apadana), reception rooms, and dependencies is classified among the world’s greatest archaeological sites. Persepolis was the seat of the government of the Achaemenid Empire, though it was designed primarily to be a showplace and spectacular center for the receptions and festivals of the kings and their empire.

AFM

Leave a Comment