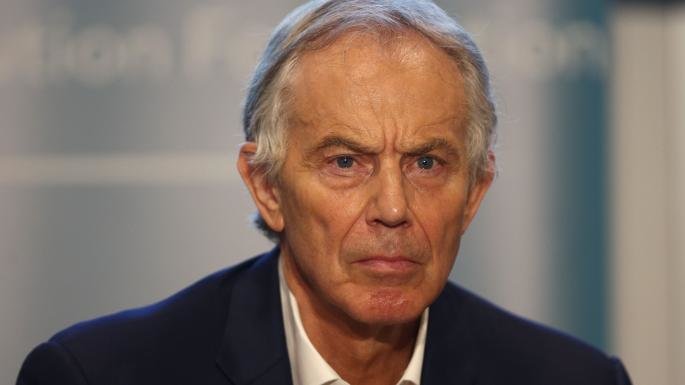

Tony Blair and a bait called Brexit

What is a warlike politician looking for?

Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair is still trying to play a major role in the country's political equivalents, under the pretext of confronting the implementation of its withdrawal plan from the European Union. This is while Tony Blair's political history has long endured in Britain. It is worth pointing out that many European politicians, especially those who are opposed to Jeremy Corbin in the leadership of the Labour Party, are secretly strengthening Tony Blair's political situation in the UK.

An overview of recent analyzes of the British political situation clearly shows how fragile and difficult the country is.

Tony Blair says Labour 'trying to face both ways' on Brexit

As The Guardian reported, Former prime minister says party would have been better to ‘fight in a clearer way’

Tony Blair has criticised Labour’s handling of the Brexit process, saying “trying to keep both sides happy is not possible”.

The former prime minister told an audience in London on Monday evening that although he would be voting for the party on 23 May, “it would’ve been better if we’d been able to fight it in a clearer way”. He encouraged remainers to “vote for one of the other anti-Brexit parties” if they cannot bring themselves to vote for Labour.

The party’s current stated policy is that it would support a second referendum under certain circumstances. Earlier on Monday, the deputy leader, Tom Watson, insisted Labour stood for “remain and reform” and said it seemed inevitable that a confirmatory referendum would be needed for the party’s MPs to agree to any Brexit deal. On Sunday, the shadow Brexit secretary, Sir Keir Starmer, expressed doubts that a Brexit deal could pass parliament if it did not include a confirmatory referendum, warning that up to 150 Labour MPs would reject an agreement that lacked one.

On Monday night, Blair also threw his weight behind holding another vote. He told the event hosted by the Guardian at the Barbican center that while Labour were right to accept the result of the EU referendum, another public poll in the event of unsatisfactory Brexit negotiations should have been party policy from the outset of talks.

He predicted the European elections on 23 May would “not [be] good news for the Tories or Labour” and said that, while a no-deal Brexit was “very unlikely”, politics in Britain was “in a unique state of unpredictability”. Politicians had lost sight of the importance of discussing domestic issues such as cuts to funding for health services and police and the lack of opportunities for young people amid Brexit chaos, he said.

“The great irony of Brexit is, the future of the National Health Service is decided in Westminster. The person who’s got the opportunity to do something about knife crime is Theresa May, not Jean-Claude Juncker [the EU commission president],” he said. “Brexit’s distractive effect is almost as bad as the destructive effect.”

Blair’s criticisms of indecisiveness extended to the Conservatives. “My view is that both the main parties have made the same mistake if you try and face both ways you end up pleasing no one,” he said. Ultimately though, Labour was an anti-Brexit party and the majority of its MEP candidates had “long credentials in fighting the case for Europe”.Although he lamented that “it would’ve been better frankly if the avowedly remain parties had been standing under one banner”, Blair stressed it was important for remainers to vote in the election because gains for Brexit parties in Europe could sway the way MPs approach the UK’s departure in parliament.

Adding that he believed that the leave vote had been partially fuelled by legitimate concerns over immigration and globalisation, Blair said the “biggest tragedy” of Brexit was “that it’s the answer to nothing”.

Brexit despair takes me back to Tony Blair!

ROULA KHALAF wrote in Financial Times that Whether you voted for the UK to leave or remain in the EU in the 2016 referendum, you have to agree that Brexit has brought out the nastiest in British politics. It has turned a prime minister into a robot, parliament into a war zone and political parties into warring tribes. As the same week plays out, time and again, with endless debate in parliament over a zombie withdrawal deal that refuses to be buried, Brexit, I am guessing, has also driven a large part of the country to despair.

In my case, this despair has led to the unthinkable: a new appreciation for Tony Blair. Yes, you heard it right. In the age of insanity, I find the former UK prime minister sane. In an era of absurdity, he brings lucidity.

Though I’ve often been reminded of New Labour’s reforms and how Mr. Blair brought peace to Northern Ireland, I had, over the years, developed something of an allergy to him. I was so hypersensitive that I was annoyed by his voice and I avoided his appearances on television. That may have been, in part, an unfortunate habit inherited from my late mother. She would, infuriatingly, switch channels whenever one of the many politicians she loathed appeared on screen.

My allergy to Mr. Blair wasn’t only due to the Iraq war debacle, or the deluded pretence that blindly following America was the most effective way to influence its behaviour. It wasn’t only the messianic zeal with which he approached liberal interventionism, reducing foreign policy complexities into a choice between good and evil. It was also that cynicism followed him long after he exited Downing Street, as he parlayed his autocratic contacts into a moneymaking machine.

A month or so ago, I caught a glimpse of Mr. Blair on TV. Instead of turning away, I focused. He was expressing a blunt truth that politicians have been tying themselves into knots to avoid — that Brexit had no solution. If you cut through the noise and the illusions, there was no way of squaring the government’s exit plans without threatening Northern Ireland’s place in the union. Suddenly I appreciated the lack of nuance that I once found so objectionable in Mr. Blair.

On a radio show another day, I heard him say that the dispute over the Irish backstop was a subset of the fundamental dilemmas of the Brexit negotiations: the choice is ultimately between a pointless Brexit, in which the UK stays closely tied to the EU and becomes a rule taker, or it sets its own rules and must accept the corresponding pain. The government has been attempting to find a middle ground that does not exist.

Like many, I am nostalgic for an era where at least one political party leader makes sense some of the time. That is neither the case with Theresa May, prime minister nor with Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn, pretty much all the time. Or perhaps I am willing to listen to Mr Blair because he confirms my view that the only sensible way out of the Brexit paralysis is a second referendum.

Mr. Blair is right to argue that if Britain is heading to a no-deal Brexit, which most MPs and the majority in the wider public oppose, then the government’s democratic duty is to return to the people. I would add that voters should be given a chance to change their minds when Mrs. May has been pressing MPs to change theirs, putting her deal to a vote three times so far. And what about hardline Brexiters’ change of heart? Jacob Rees-Mogg once attacked Mrs. May’s deal for “turning the UK into a slave state”. Last week he voted for it.

I suspect that I am not alone in reassessing Mr. Blair. I doubt, though, that his shattered credibility will be rehabilitated, however, wise his words on Brexit. I often hear him blamed for sowing the seeds of the distrust that now infect our politics. He bears responsibility too for the British public’s backlash against immigration, having opened up Britain’s borders to eastern European EU countries in 2004.

The best Mr. Blair could hope for is that his legacy will be put in greater perspective. His consolation may be that the Tory prime ministers in power after Labour — David Cameron and Theresa May — have both so unashamedly put party ahead of country that they are guaranteed an even less auspicious place in history.

The Post-Brexit Paradox of ‘Global Britain’

Soohia Gaston wrote in The Atlantic that Brexit is an all-consuming maelstrom of political dysfunction, one that has compelled Britain’s eyes inward. Yet amid the chaos, Prime Minister Theresa May has been steadfast in her determination that the country’s international role should not succumb to the same myopic fate as its departure from the European Union has.

In the febrile early months following the June 2016 referendum when Britain voted to leave the EU, its allies were fearful that the vote would see the country’s drawbridges snapping upward. Sensing the urgent need for optimism, May and her then–foreign secretary (and now possible successor), Boris Johnson, gave bold speeches, setting out ambitions for what they called a “truly global Britain.” Conjuring an image of a triumphant, swashbuckling nation retaking its rightful place on the world stage, a global Britain embodies the promise of a Brexit dividend, one in which the country is no longer hemmed in by what Brexiteers see as a European cage.

Almost three years on—through failed parliamentary votes, cabinet resignations, and May’s announcement that she will step down as prime minister—this mantra of internationalism remains one of the few legacies of May’s premiership. So far, however, a global Britain has been nothing more than a hollow promise.

With British diplomats struggling to convince their international peers of the phrase’s fundamental purpose and meaning, a cross-party group of lawmakers leading the parliamentary Foreign Affairs Select Committee warned last year that “Global Britain” had only succeeded thus far as “a superficial rebranding exercise.”

At the heart of the global Britain promise is a great paradox: Those who are most naturally inclined to support such an idea—young, university-educated, well-traveled Britons—fundamentally resent the notion that any project forged on the back of Brexit could be truly internationalist.

Foreign policy has often served only as a sideshow to British domestic politics. However, with Brexit sparking complex new conversations about trade, diplomacy, and defense policy—as well as more elemental questions about Britain’s role in the world—foreign affairs may well become one of the most active battlegrounds of Britain’s deepening social fault lines. And with about a dozen contenders lining up to replace May as Britain’s prime minister, the future of the ”global Britain” catchphrase and the strategy it was intended to inspire will become central to the Conservative Party’s, and the country’s, future. False silos that have long separated domestic and foreign policy will have to come down.

“Foreign policy isn’t about foreigners,” Tom Tugendhat, a Conservative member of Parliament and the chair of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee, told me. “It’s about us, and how we shape the world around us in the interest of our people, our friends, and partners.”

It won’t be easy: New research I have conducted with the British Foreign Policy Group, an educational think tank, and the pollster BMG makes clear that Britain is phenomenally divided on the country’s international identity, spearheaded by a government unable to make the trade-offs necessary to truly achieve the idea of a global Britain. The notion that citizens will instinctively support the costs necessary to become a more prominent military, diplomatic, and trading power does not stand.

Political momentum is instead building behind those who see more downsides than upsides in our changing world, and for whom liberalism and internationalism inspire suspicion, mistrust, or even fear. These Britons generally have lived less mobile lives, hold identities more closely rooted in their communities, and are less bothered by events outside the confines of the nation. For example, just 6 percent of those who traveled abroad frequently last year consider immigration to be an important issue, compared with 44 percent of those who didn’t leave Britain. Among those who never stray abroad, there is, to be sure, a significant degree of distinction between people whose socioeconomic circumstances have hampered their access to international opportunities and the older, wealthier Britons who have chosen to prioritize an exclusive national identity.

With the clock ticking on May’s premiership, the paradox of a global Britain she unwittingly exposed will need to be reconciled by her successor. The candidates jostling to replace her as the Conservative Party leader and, by extension, prime minister, appear committed to championing a global Britain, but have not yet articulated any means of persuading the large swaths of the country skeptical of internationalism to fall in line. If her successor calls for a general election and the opposition Labour Party comes to power, it will face its own reckoning around the discord between its membership’s broad support for international institutions and its leadership’s radical positions on unilateral nuclear disarmament, NATO, and the military.

For now, however, the challenge falls to the party that has made itself the party of Brexit and a global Britain, without delivering either.

Conclusion

The British prime minister is looking for a way to revive his lost political position in Britain and the Labor Party. He is attempting to abuse the feelings of some British citizens. This suggests that Tony Blair has not made any difference with his prime minister. At that time, Ton Blair tricked British citizens into the Iraq war, and this time, he has made such a move on Brexit.

Leave a Comment