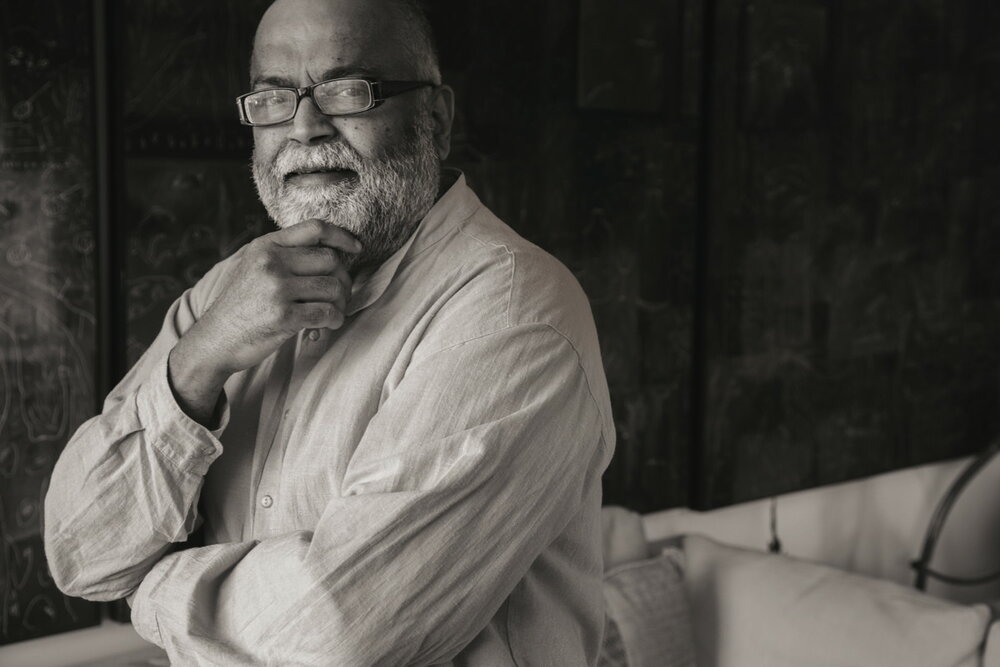

I am optimistic about the future of resistance and emancipation: Arjun Appadurai

TEHRAN - Dr. Appadurai is a prominent contemporary social-cultural anthropologist, having formerly served as Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs at The New School in NYC. He has held various professorial chairs and visiting appointments at some of top institutions in the United States and Europe. In addition, he has served on several scholarly and advisory bodies in the United States, Latin America, Europe and India.

Dr. Appadurai is world renowned expert on the cultural dynamics of globalization, having authored numerous books and scholarly articles. The nature and significance of his contributions throughout his academic career have earned him the reputation as a leading figure in his field. His latest book is The Future as Cultural Fact: Essays on the Global Condition (Verso: 2013). He is a Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Following is the text of her interview with Asre-Andisheh Magazine:

Q: How do you explain the relation between globalization and westernization? Do you thinks that globalization amounts to westernization and all indigenous cultures are doomed to be westernized and Americanized sooner or later or do you believe that globalization is a more complicated process so that no single culture can dominate the globe and we should recognize pluralism and relativism?

A: No, I have long argued that Westernization and modernization are not the same thing. The world is not doomed to either Westernization or Americanization. For at least fifty years, the decolonized nations of Asia, Arica, the Middle-East and Latin America have been evolving their own modernities, which reflect their specific historic conditions and often are efforts to rewrite the present in their own terms. We can still see this today in the arts, cultural politics, social movements and literatures of the world, though the pressure from powerful countries and corporations to commoditize these modernities is also very strong.

Q: Do you consider indigenous cultures in the global south capable enough to resist and challenge western forms of power relations? What are the potentials of this resistance?

A: This is a difficult question. The states in many of these societies often try to compete in global markets, both cultural and economic, and so they often try to mimic or replicate dominant models, often from the West. But in many decolonized countries, there are powerful movements involving artists, intellectuals, activists and ordinary citizens to resist and reorganize to address the force of modern Western hegemonies. The resources for such efforts to resist are always limited, for they do not usually have large or reliable sources. They must rely on the resources of imagination and aspiration and they are frequently faced with efforts to repress or marginalize them, both from forces outside their countries and from the ruling elites of their own countries. Thus, they do have a good chance, but the effort is always hard and the outcome is hard to be certain about.

Q: We can regard the Islamic Revolution in Iran as a counter hegemonic resistance against global imperialism which has survived for about four decades in spite of all pressures, sanctions and threats and it is inspired by other liberation movements. How do you see this resistance experience? What are the reasons of its survival?

A: The Iranian experience since the Islamic Revolution of 1989 is remarkable. It is a major case of resistance to Western imperialism, and to the forces of Israel, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Syria. This has required a political alignment with Russia and China, but this has not been accompanied by cultural imperialism from the East. Iran remains a source of major democratic struggles, brilliant artistic expressions (such as Iran’s alternative cinema) and significant progress in women’s rights and literacy. Iran’s challenge is not in the realm of culture but in the realm of equality, democracy and the right to dissent.

Q: Both Iranians and Indians have anti colonialist experiences in their contemporary history. So are there any chance for cooperating and coordinating resistance policies against the new forms of imperialism, given the fact that the two nations have linguistic, cultural and civilizationonal similarities and interactions throughout a long history?

A: It is true that India and Iran have similar histories as strong, independent postcolonial countries. Today, the two governments are in an active strategic dialogue, but it is mostly based on oil and negotiating mutual political interests. It needs to be a more active dialogue in the realms of art, education and popular social movements. This sort of dialogue has a great deal of potential since it can build up on centuries of shared Indo-Persian collaboration and exchange.

Q: Are you optimistic about the future of resistance and emancipation in the global south? What are the fears and hopes in this regard? Specifically how do you define emancipation?

A: I am optimistic, mainly because people who are in much more difficult circumstances than my own, such as refugees, dissidents and activists who face daily repression and disappointment, are themselves optimistic. So how can I afford to be pessimistic? For me, emancipation is that political condition in which the dreams and hopes of intellectuals and scholars will converge with those of poor, weak and marginal populations across the world, so as to produce a decisive victory against the forces of corporate capitalism and religious intolerance.

Leave a Comment