Will south Syria replicate south Lebanon’s experience?

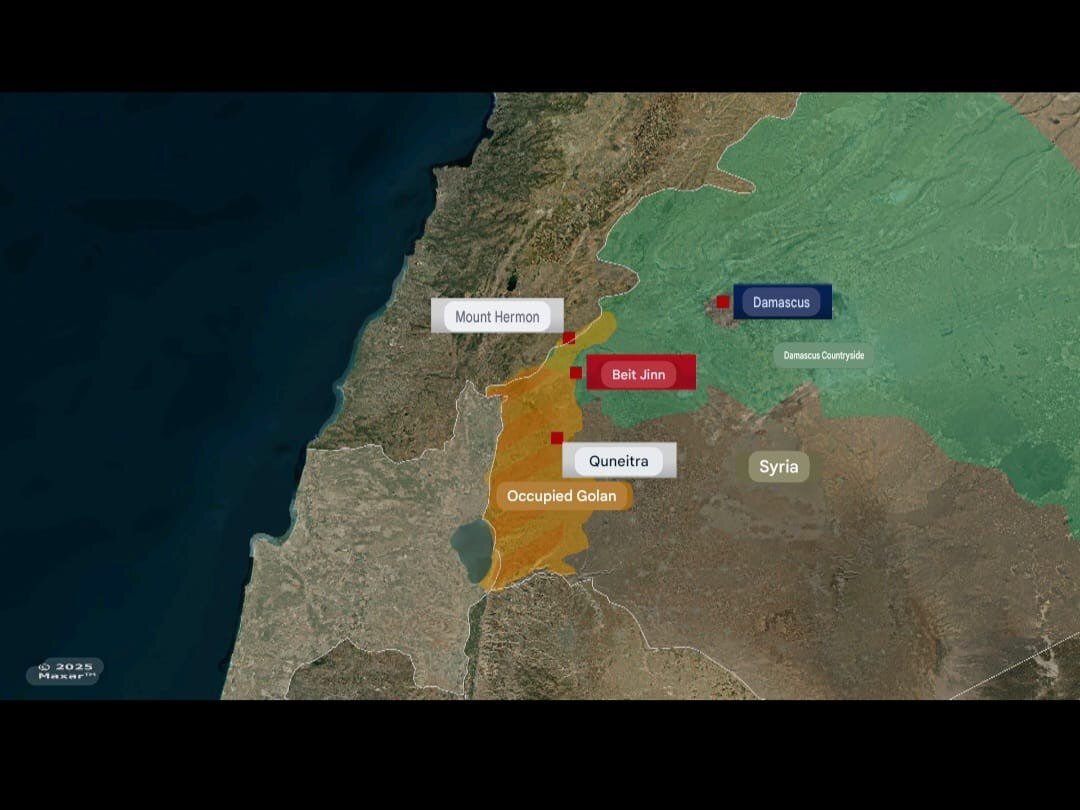

BEIRUT — The dramatic events that shook Beit Jinn Friday at dawn have revived a question long whispered in regional security circles: Is south Syria on the cusp of developing its own south Lebanon–style Resistance model?

The unprecedented escalation unleashed by the Israeli enemy—after a direct clash with a local armed cell—revealed patterns that echo the early days of Lebanon’s anti-occupation awakening.

The confrontation began when an Israeli occupation patrol crossed into Syrian territory to arrest three local civilians.

However, a small group of people ambushed the patrol, injured and nearly captured the soldiers after disabling their vehicle.

Their fleeing triggered a sweeping and punitive response: hours of air and artillery strikes flattened around twenty civilian homes, forcing families to flee under the weight of bombardment.

By midday, thirteen civilians had been killed, with more expected as bodies remained beneath the rubble.

Israeli media quickly confirmed the gravity of the incident. Wounded soldiers were airlifted to Sheba Medical Center—five in total, three in critical condition.

Hebrew-language outlets reported frustration inside the Northern Command, criticizing poor planning that left the patrol “exposed and blind.” One paper admitted bluntly: “South Syria remains an area where anyone with a weapon targets us immediately.”

This admission matters. It mirrors precisely how the Israeli enemy once described south Lebanon during the occupation years: a landscape impossible to control, a population unwilling to submit, and a frontier that refuses to be pacified.

More importantly, the events in Beit Jinn shattered a critical illusion. For years, the Israeli enemy has attempted to normalize its incursions—small, steady, deliberately unchallenged acts meant to train the population into coerced silence.

Friday’s ambush, however, produced the opposite effect: a psychological rupture. It showed that, despite exhaustion, displacement, and the erosion of state authority, local communities can still generate fighters, operate independently, and challenge the Israeli enemy without waiting for political endorsement.

This is exactly what happened in south Lebanon in the 1980s. The Lebanese Resistance was not born through official decision-making; it emerged because the state was absent, the occupier was brutal, and the people—ordinary farmers, students, laborers—decided to protect their dignity when no one else could.

South Syria today holds many of the same ingredients: a weakened central authority; rural communities repeatedly exposed to cross-border violence; and deeply rooted social networks capable of producing local defense formations.

The Israeli enemy’s greatest fear is that Beit Jinn becomes a template. One village resisting encourages another, especially those with their own history of killed civilians, missing relatives, or repeated incursions.

Israeli analysts have already warned that allowing even a small group to operate freely on the Syrian frontier would constitute a “fatal strategic error”—a phrase once used, almost verbatim, to describe the early Hezbollah cells in South Lebanon.

Whether south Syria fully replicates the south Lebanon model depends on one decisive element: the will of the people when the state cannot shield them. And the signs emerging from Beit Jinn suggest that this will is awakening, quietly but unmistakably.

At this crossroads, the words of the Islamic Revolution Supreme Leader, Sayyed Ali Khamenei, on December 22, 2024, resonate with striking relevance: “The Syrian youth have nothing to lose. Their universities, schools, homes and lives aren’t safe. What can they do? They must stand with firm determination against those who have orchestrated and brought about this insecurity, and God willing, they will prevail over them.”

This statement captures the strategic core of the moment. When a generation is stripped of safety, opportunity, and normalcy, it does not retreat—it transforms.

The pressures that might break a society instead forge its most resilient defenders. In this sense, the Syrian youth stand exactly where the young men of South Lebanon once stood: confronted with danger, yet animated by a fierce clarity that defending one’s land is no longer a choice but an obligation.

If Beit Jinn is a preview, then the message is unmistakable: Syrian youth will prevail—not because they seek war, but because war has been forced upon their homes, their streets, and their very existence. And like the youth of South Lebanon before them, they may soon decide that history does not wait for permission. It is made by those who refuse to live without dignity.