How America’s war on Chinese tech backfired

In late September, the Biden administration issued a draft rule that would ban Chinese connected and autonomous vehicles and their components from the U.S. market. This is one of the latest of many steps that U.S. policymakers have taken to protect the United States’ economic security. Under the first Trump administration, Washington placed restrictions on the telecom companies ZTE and Huawei. President Joe Biden has maintained many of Trump’s policies toward China and advanced new ones, including initiating broad export controls in late 2022 on advanced semiconductors and semiconductor equipment. As the incoming Trump administration appears ready to accelerate and expand these restrictions further still, it’s worth considering the track record of these policies—and take stock of the tradeoffs that they entail.

Washington’s array of tools is highly expansive: export controls, tariffs, product bans, inbound and outbound investment screening, constraints on data flows, incentives to shift supply chains, limits on scholarly exchange and research collaboration, industrial policy expenditures, and buy-America incentives. The goals of these measures are equally diverse: slow China’s progress in the most advanced technologies that have dual-use potential, reduce overdependence on China as a source of inputs and as a market for Western goods, deny China access to sensitive data, protect critical infrastructure, push back against economic coercion, protect the United States’ industrial competitiveness, and boost its manufacturing employment.

Beijing’s shift toward a more expansive and assertive form of mercantilist techno-nationalism poses genuine risks to the prosperity and economic security of the United States and others. Something must be done, to be sure, but Washington’s increasingly restrictive policies have yielded highly mixed results. Take the goal of slowing China’s technological progress at the cutting edge and maintaining the United States’ relative technological advantage. In pursuit of this objective, Washington has seen progress in some areas, such as slowing China’s semiconductor sector, but witnessed even more rapid Chinese success in others, such as in electric vehicles and batteries. There are inherent tensions between Washington’s various economic security goals, with progress in some inevitably slowing progress in others. Additionally, U.S. policymakers have not adequately considered how China and others would adapt to U.S. restrictions.

U.S. restrictions on Chinese technology have yielded unintended consequences.

As President-elect Donald Trump returns to power, his administration would be wise to reflect on the fact that existing restrictions on Chinese technology have yielded decidedly mixed results. The Biden administration has described its strategy as a “small yard, high fence,” or placing high restrictions on a small number of critical technologies. That yard is already growing, with negative unintended consequences for the United States. If the Trump administration pursues an even broader decoupling, the costs will be magnified exponentially.

Mixed results

The effectiveness of U.S. actions looks clearest when examining the state of the specific companies and industries that have been targeted, particularly with export controls and restricted access to the American market. China’s semiconductor industry has encountered the most difficulties. Over the last few years, the U.S. Commerce Department has placed roughly 850 Chinese institutions and individuals on its Entity List, which effectively bars them from gaining access to the United States’ most advanced technology. In October 2022, the Commerce Department also imposed severe restrictions on U.S. firms selling advanced semiconductors and equipment to Chinese companies. Washington also compelled other chip powerhouses, most notably Japan and the Netherlands, to restrict sales to China. The impact was immediate and devastating for several Chinese firms, which were no longer able to buy certain chips, such as Nvidia’s most advanced semiconductors used in artificial intelligence applications. Moreover, Western equipment and software providers walked out of their manufacturing facilities in China, leaving the Chinese to figure things out for themselves. As one Chinese executive recently told me, “We went from being cooks in the kitchen to farmers in the field.” Lower yield rates and poorer performance left the affected firms further behind their Western competitors than before.

Beijing has given Chinese chip firms a blank check and every regulatory incentive imaginable in an effort to fill these holes and close the gap, but they are still far behind their counterparts in the United States, Japan, and South Korea. And Chinese manufacturing equipment makers and software providers are even further behind. Entrepreneurs at Chinese AI firms told me that the banning of Nvidia’s chips has hampered their efforts to train their large language models and develop other kinds of bespoke business applications.

We went from being cooks in the kitchen to farmers in the field.”

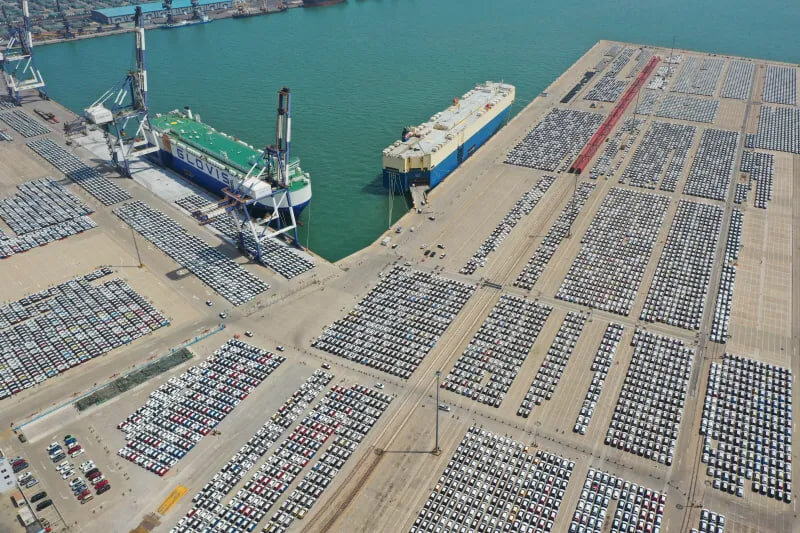

Now, the United States is in the early stages of adopting measures against other industries. The high tariffs Biden imposed on electric vehicles and batteries this year, coupled with the potential forthcoming ban on imports of connected and autonomous vehicles, will effectively make the U.S. market off-limits to all Chinese automakers. It is possible the United States will even block U.S. pharmaceutical firms from using Chinese companies to conduct clinical trials, restrict U.S. pharmaceutical investments in China, and disallow drugs developed in China from accessing the U.S. market. And if China can ramp up production for its new commercial airliner, the C919, and start to export it around the world, Washington may well add some of the plane’s U.S.-made components to the export control list, which would be a crushing blow to COMAC, the Chinese producer, given that almost every system that keeps the C919 in the air is from a U.S. or European supplier.

Beyond individual sectors, U.S. pressure is indirectly dampening China’s economy. Treating China as a strategic competitor has led the leadership in Beijing to emphasize national security even more than was already the case. Beijing’s hyperfocus on technological self-reliance has meant overinvestment in high-priority sectors, generating oversupply, which has hurt the bottom line of many Chinese companies and generated tensions with trading partners. The resulting uncertainty has not sat well with Chinese private entrepreneurs and many households, contributing to a decline in investment and consumption. Beijing deserves much of the blame for a slowing economy, but its policies are to some degree a response to growing Western pressure.

Many Chinese economists are alarmed by the nationalistic direction of their country’s economic policy and skeptical that self-reliance will work. They believe that a return to a more market-friendly approach is necessary. Some have aired their worries publicly, but the danger to their careers is real, and so most keep quiet.

Unintended consequences

As damaging as Western restrictions have been, the tightening controls have also spurred Chinese technological advances that otherwise would not have occurred. When I recently asked about whether U.S. restrictions have unintentionally incentivized China’s tech efforts, one U.S. official involved in these policy deliberations retorted, “Wouldn’t they have done all of this anyway?” The answer is an emphatic “no.”

Since the Opium War ended in 1842, China has made greater self-reliance a strategic goal. But the recent U.S.-led measures have resulted in Beijing turbo-boosting this mission. The core goal of the country’s “Made in China 2025” plan, announced in 2015, was to raise the prominence of Chinese technology products in global markets. It wasn’t until after Washington began flexing its muscles that Beijing’s aim shifted toward indigenizing its supply chains from beginning to end, particularly in strategic technologies such as semiconductors, telecom, and artificial intelligence. Over the last five years, China has invested extensive resources in the most advanced areas of semiconductor equipment and tools, and Beijing also has tried to develop high-tech solutions based almost entirely on Chinese components in an effort to “Delete A”—that is, remove American tech from their supply chain.

The U.S.-Chinese tech conflict, once a preoccupation of Chinese officialdom, has now become integral to the business strategy of both state-owned and private firms. Whether for reasons of national loyalty or commercial ambition, Chinese companies and research organizations have aimed their sights higher and higher, expanding investments and R&D beyond their shores, in Southeast Asia, Europe, and Latin America.

Ironically, the very restrictions meant to curb China’s technological progress have, in some areas, helped to spur it. China has seen improvements across multiple sectors, in terms of research and development, manufacturing output, and greater domestic content in exports. My own recent visits to Chinese electric vehicle battery firms and automakers revealed companies that have a clear sense of the global competitive landscape, strong capabilities in product and process innovation, and the financial resources to get ahead. The top representatives of foreign firms in China are upset with China’s discriminatory industrial policies, but they now consistently emphasize that their main challenge is a growing cohort of highly capable Chinese competitors.

Chinese firms are still far behind the competition in the semiconductor industry, but they are gradually building a domestic ecosystem and supply chain. They are hoarding foreign lithography equipment and making incremental progress with local equipment and software makers. Domestic firms appear to be following Beijing’s instructions to increase the use of domestic chips. Chinese researchers are exploring new pathways in materials, chip architecture, and computing methodologies that could potentially allow Chinese semiconductor manufacturers to leapfrog their foreign rivals in the same way that Chinese makers of electric vehicles have surpassed Western dominance in internal combustion engines. When I queried Chinese AI tech executives about which Chinese firms are most likely to succeed in semiconductors and AI, they most often mention Huawei, a firm that was knocked down, but not out, by U.S. sanctions. Its smartphone business took a huge hit, but it now has an entirely independent operating system, Harmony, running on its devices.

China is also now outcompeting the United States and the rest of the world in cleantech. Its risky bet on electric vehicles has paid off, with impressive results in raw-material processing, batteries, telematics, car models, and charging infrastructure. The same is true for solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear power. Most recently, Chinese firms have made substantial progress in the development of autonomous vehicles and the related infrastructure. China is also the source of a growing share of innovative drugs that reach late-stage trials and enter global markets. And even as Western multinationals are diversifying away from China, some of the largest new investors in Southeast Asia, Europe, and Latin America are Chinese companies. Tech restrictions meant to deny them access to Western technology are leading them to globalize and build extensive transnational networks faster than they otherwise would have.

Economic blowback

The United States' economic security measures have both slowed and accelerated China’s tech drive.

U.S. policymakers must weigh how the United States' economic security measures have both slowed and accelerated China’s tech drive. Beyond that, they must take stock of how these measures have shaped the United States’ own technological trajectory. Here, too, the results have been mixed.

Major pieces of legislation, such as the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, have budgeted over $600 billion for basic sciences, the semiconductor industry, cleantech, and other investments. Such measures also are meant to mobilize private capital and foreign investment, and there has indeed been a surge in investment in semiconductor fabs, electric vehicle batteries, and other technologies.

But Washington has also placed restrictions on U.S. innovation that so far outweigh the good that has come from the investments. Export controls have reduced business opportunities for American semiconductor firms; less revenue means less investment in R & D and less innovation. Specific restrictions, coupled with the chilling effect produced by increased geopolitical tensions, have reduced opportunities and income for U.S. firms.

The U.S. Justice Department has placed restrictions on scholarly cooperation with China, causing the productivity of American science and technology scholars to drop. A high proportion of AI scientists in the United States hail from China; a decline in their numbers means a drop in innovation in the United States and more opportunities for others, including China, to step up. Washington has also imposed restrictions on Chinese students pursuing science and technology graduate degrees in the United States, depriving American universities of many highly talented students.

As the Chinese government has pushed indigenous solutions, Chinese companies have tried to excise American technology from their products and ecosystems. There are signs that other countries, worried about high tariffs and other restrictions, are also shying away from American technology.

Higher tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles will shield U.S. automakers from unfairly priced imports, and a ban on Chinese connected and autonomous vehicles will reduce data security risks of American consumers. But such protection likely means fewer American electric vehicle models, continued high prices, a slower energy transition in transportation, and less competitive U.S. firms internationally.

Industrial policy may nurture some infant industries that otherwise would not develop, but it is just as likely that Washington will spend profligately on white-elephant projects. Each of the new multibillion-dollar semiconductor fabrication plants being built in the United States, partially at American taxpayers’ expense, may be defensible. But given concurrent state-backed investments in fabrication plants in Brazil, China, the European Union, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, it is highly likely that there will be substantial global overcapacity within the next decade, which will mean some of today’s investments will be unsustainable, resulting in unsold inventories, underperforming firms, and job losses.

It is likely that in at least a few sectors the United States and its allies are gradually sharing, or even ceding, leadership to Chinese counterparts, measured not by the technical feat of any individual technology but by dominance of ecosystems and diffusion of their products. Although China’s emergence as a science and technology powerhouse is not simply the result of responding to Western pressure, tensions have likely accelerated its progress. As Chinese firms broaden their reach, U.S. technology will be less indispensable in some parts of the world.

The middle path

De-risking—reducing the vulnerabilities that the United States and its allies face from technology leakage to China, overdependence on Chinese supply chains, and insecure data and critical infrastructure—has brought some improvements in the United States’ economic security, but there have been substantial unintended consequences. And if the Trump administration takes even more radical steps to decouple the U.S. and Chinese economies, the economic and national security downsides will be even more pronounced.

Washington should take steps to ensure that the United States continues to make pathbreaking advances in science and technology. The incoming Trump administration and Congress need to recognize that there are potential tradeoffs between economic prosperity goals, such as greater innovation and wealth, and economic security goals, such as greater resilience and protecting against technology leakage. U.S. policymakers must set measurable goals, conduct cost-benefit analyses of different policy options and scenarios, and carefully evaluate the actual results of various policies.

Washington needs to set clear priorities, identifying the most urgent threats that deserve a response. Otherwise, the United States will be dragged into a game of whack-a-mole or, more worryingly, try to block all commercial ties with China. To the extent that the United States attempts to deny technologies to China, the only sustainable approach involves working with allies and other countries so that the United States is not outflanked by China and lose technology leadership in the rest of the world. If the Trump administration pursues extensive decoupling from China, the result will most likely be an isolated, poorer, and weaker United States.

The Trump administration would also be unwise to ignore global institutions, such as the World Trade Organization, as doing so would dramatically raise the likelihood of unbounded conflict. Instead, Washington should intensify multilateral cooperation to set new rules for global economic activity in order to avoid a race to the bottom. The United States may in some instances need to take unilateral steps to maintain its relative technology superiority, but excessive economic security measures will mean less innovation, slower economic growth, reduced profits, and fewer jobs. With a combination of wise domestic policies, collaboration with allies, and investment in international institutions, the United States can achieve both prosperity and security.

* Scott Kennedy is senior adviser and trustee chair in Chinese Business and Economics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

(Source: Foreign Affairs)