China emerging as a flexible peacemaker in West Asia: Foreign Affairs

TEHRAN - In a commentary published on March 15, Foreign Affairs analyzes how China has emerged as “flexible peacemaker” in West Asia (Middle East).

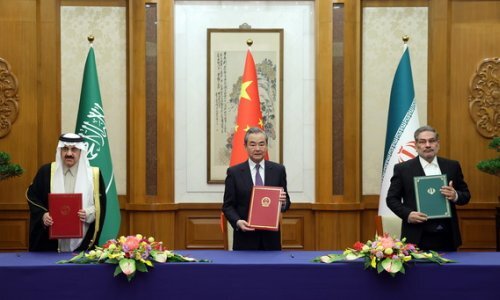

The analysis followed after China brokered an agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia after seven years of estrangement.

Foreign Affairs suggests that Washington’s interests would be better served if it stopped taking sides with some Western Asian states at the cost of others.

“U.S. interests would be better served if Washington stopped taking sides in regional disputes, got back on talking terms with all key regional players,” it notes.

Following is part of the commentary titled “How China became a peacemaker between Iran and Saudi”:

While U.S. President Joe Biden’s Middle East team was focused on normalizing Saudi-Israeli relations, China delivered the most significant regional development since the Abraham Accords: a deal to end seven years of Saudi-Iranian estrangement. The normalization agreement signed on March 10 by Riyadh and Tehran is noteworthy not only because of its potential positive repercussions in the region—from Lebanon and Syria to Iraq and Yemen—but also because of China’s leading role, and the United States’ absence, in the diplomacy that led to it.

Washington has long feared growing Chinese influence in the Middle East, imagining that a U.S. military withdrawal would create geopolitical vacuums that China would fill. But the relevant void was not a military one, created by U.S. troop withdrawals; it was the diplomatic vacuum left by a foreign policy that led with the military and made diplomacy all too often an afterthought.

The deal represents a win for Beijing. By mediating de-escalation between two archenemies and major regional oil producers, it has both helped secure the energy supply it needs and burnished its credentials as a trusted broker in a region burdened by conflicts, something Washington couldn't do. Chinese success was possible largely because of U.S. strategic missteps: a self-defeating policy that paired pressure on Iran with supplication to Saudi Arabia helped China emerge as one of few major powers with clout over and trust with both of these states.

Beijing has worked to strengthen its relations with all regional powers without taking sides or getting entangled in their conflicts.

Yet Washington does deserve some credit for the agreement—if not the kind of credit it would want to claim. In inadvertent ways, its conflicted approach to the region spurred Saudi Arabia’s shift from confrontation toward diplomacy with Iran and thereby opened the way to Chinese mediation. As long as U.S. partners such as Saudi Arabia believed they had carte blanche from Washington, they had little interest in regional diplomacy. Once Riyadh believed that the carte blanche had been withdrawn, diplomacy became their best option.

After four days of negotiations in Beijing, a joint trilateral statement announced an agreement between Saudi Arabia and Iran to reopen embassies and resume diplomatic relations within two months. The two countries affirmed respect for each other's sovereignty and noninterference in each other’s internal affairs and revived old security cooperation and trade agreements. The deal included a future meeting between the Saudi and Iranian ministers of foreign affairs to implement the agreement and discuss means of enhancing bilateral relations.

Iraq launched efforts to defuse Saudi-Iranian tensions in 2020. At first, the Iraqis were passing messages between the two sides. By April 2021, Iraqi facilitation had turned into mediation, eventually yielding six face-to-face meetings in Iraq and Oman between Iranian and Saudi officials.

While Trump’s gravitation away from the Middle East pushed Saudi Arabia toward diplomacy, Biden’s subsequent “back to basics” approach also helped pave the way for China’s emergence as the new peacemaker. Even as it sought to shift the focus of U.S. foreign policy to other challenges and pledged to make Saudi Arabia a “pariah” for the murder of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, the Biden administration also set out to reassure regional partners that it remained committed to Middle East security. An earlier Biden plan to significantly reduce U.S. troop levels in the region was shelved. In large part, this was motivated by a global view of great-power competition, which reinforced the need to shore up partnerships that could counter Chinese influence. “Let me say clearly that the United States is going to remain an active, engaged partner in the Middle East,” Biden said in a speech during his visit to Saudi Arabia last year, adding, “We will not walk away and leave a vacuum to be filled by China, Russia, or Iran.” As Defense Undersecretary Colin Kahl put it in a speech at the Manama Dialogue forum in Bahrain last November, the U.S.-China struggle “is not a competition of countries, it is a competition of coalitions.”

As a result, Washington believed it needed to keep its partners close lest they “defect’ to China or side with Russia in its invasion of Ukraine. With Saudi Arabia, Biden went from his “pariah” pledge and efforts to promptly end the war in Yemen to visiting the kingdom and pressing it to increase oil production. But Saudi Arabia sided with Russia in its war on Ukraine when it led a two-million-barrel OPEC+ production cut, refused to join Western sanctions on Russia, and welcomed Chinese President Xi Jinping for a historic Chinese-Arab summit in Riyadh. Washington was left in a worst-of-both-worlds position, not entirely trusted by its own partners but far too close to one to maintain any pretense of impartiality, leaving a vacuum that China has now begun to fill.

If U.S. continues to make itself part of the problem rather than the solution, its room for diplomatic maneuvering will become more limited.

Beijing has worked to strengthen its relations with all regional powers without taking sides or getting entangled in their conflicts. It has managed to maintain good relations with Iran, Israel, and Saudi Arabia while remaining fully neutral on the squabbles among them. China has no defense pacts with any Middle Eastern power and does not maintain military bases in the region, relying on economic rather than military influence. This approach has enabled it to emerge as a player that can resolve disputes.

Washington’s response to the deal has been, on the one hand, to welcome the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement (praising “any efforts to help end the war in Yemen and de-escalate tensions in the Middle East region”) and, on the other, to downplay the importance of Chinese mediation. “What helped bring Iran to the table was the pressure that they're under, internally and externally—not just an invitation by the Chinese to talk,” stressed John Kirby, the spokesman for the National Security Council. Yet Saudi-Iranian talks on normalization have been ongoing for several years now, long before the protests in Iran broke out last year or the additional sanctions Biden has imposed on Iran since taking office.

At the end of the day, a more stable Middle East where the Iranians and Saudis aren’t at each other's throats also benefits the United States: If nothing else, instability jeopardizes the flow of oil from the region and adds a hefty risk premium to gas prices. But while not exactly worrying about China’s role, Washington should take it as a warning—and a lesson. If the United States continues to embroil itself in the conflicts of its regional partners, making itself part of the problem rather than the solution, its room for diplomatic maneuvering will become more and more limited, ceding the role of peacemaker to China. Instead, U.S. interests would be better served if Washington stopped taking sides in regional disputes, got back on talking terms with all key regional players, and helped develop a new security architecture in which a reduced American military presence encouraged Middle East powers to share the responsibility of their own security.

The United States should not leave Middle East states with the perception that America is an entrenched warmaker while China is a flexible peacemaker. Fortunately, it is entirely in Washington’s own hands to prevent such a scenario.