Mahnaz Fathi: It was difficult persuading her to allow the sharing of her memories!

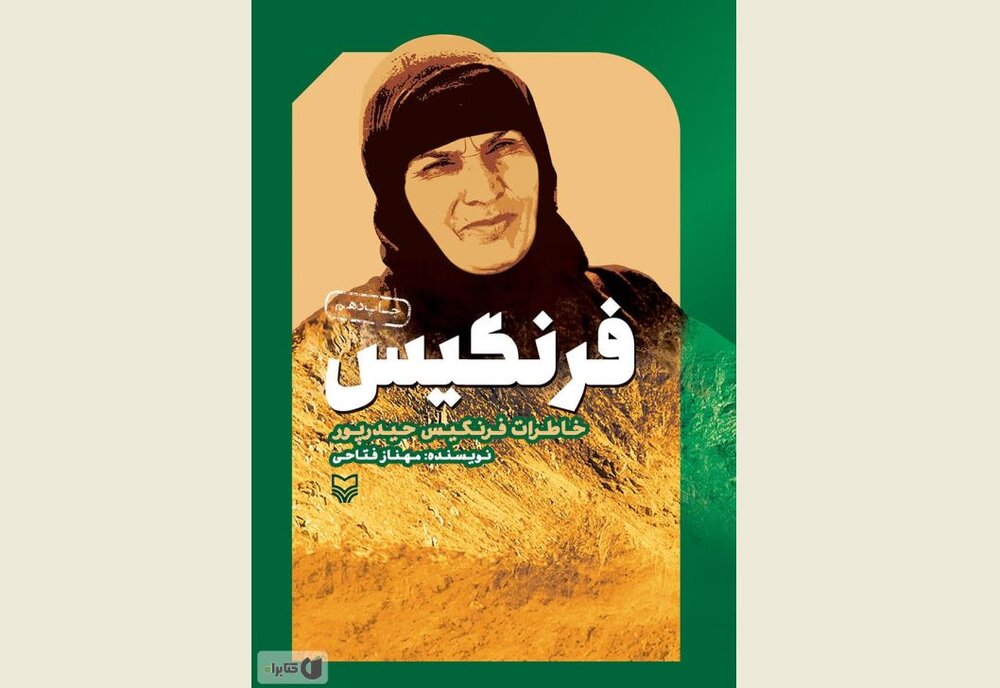

The author of "Farangis," is Mahnaz Fatahi, who had the opportunity to meet the Supreme Leader after her book had been commended by him last week.

* What led you to choose to write about the war years?

My father was a soldier, and we used to live in Kermanshah's border regions. As a result, we sensed the beginning of the war much before it was declared to have begun. We were bombed in the city or evacuated during the eight years of the war, and I have written and worried about this since I was a child. Later, the war came to an end, we grew up, and I finished my education, but the war had already shaped my life.

* What things did you write about when you were a child?

When I was a member of the intellectual development center, which had a section where it assisted children who enjoyed poetry and stories, I used to write memories, poems, and stories to express my feelings. Even with the bombers present at the time, I continued this activity.

* What drew you to Farangis's memories?

When a woman accomplishes a significant, masculine feat, as Farangis did, for instance, this kind of thing is very shocking and intriguing. The sight of a statue of this woman on the city's main street drew me in. She killed one Baathist soldier and captured another.

* Wasn't it hard to collect and write these memories?

It was very difficult! Farangis lives in Gilangarb, while I reside in Kermanshah. It takes a while to travel back and forth and is a three-hour drive there. At first, Farangis did not want her memoirs to be published, and it was challenging to persuade her. Everything had conspired to make writing challenging because of her extensive suffering.

* What, in your opinion, separates men from women when it comes to their memories of war?

Women's memoirs have feminine undertones and qualities that make the book more appealing, and reading from a woman's perspective is different from reading from a man's perspective, especially considering that these women were typically in the background. You can observe the activities and daily life in the village where Farangis is located.

* Wouldn't it be challenging for you to start writing again if you were offered a narrative similar to Farangis?

Even though it's challenging, I'll definitely write about it. Generally speaking, it is demanding to write about the holy defense and to want to transport readers back to that period after 30 years, but because we gain many experiences through this process, it is valuable, and when the book is seen, the fatigue vanishes.

* Since you write stories and are involved in memory writing, you must have encountered the problem that authors frequently alter the original story in an effort to make the memory more enticing. This type of work is meant to keep the audience, but real space distorts memories. How do you walk the fine line between keeping the reader engaged and, of course, not distorting the memories when writing memoirs?

I think it's important to keep the original memories and customs alive. And I believe that literary language can be used in a way that makes these memories appealing to the reader, provided that it doesn't damage the essence of the narrations and memories. This interference shouldn't occur in the adventures, of course.

* Do you also pen works aimed at educating children about the war?

The Bitter Taste of Dates, my first book, was my memories and is written in the style of a story. It is about the war as seen through the eyes of children. I also have other books because I am familiar with the story and the emotional and psychological environment of children. My most recent book is "Gambi," which means "lost," and it's a children's book about the holy defense.