Falk talks of Western hypocrisy regarding refugees, occupation

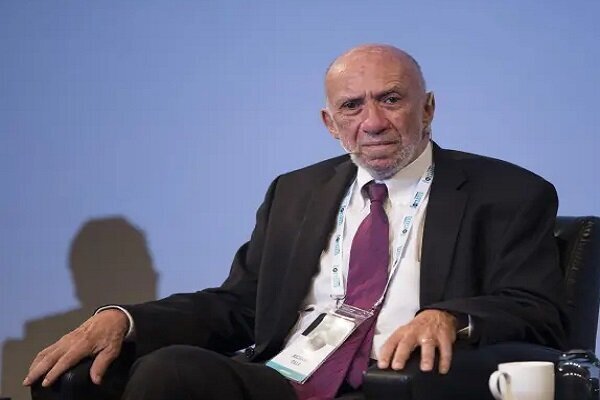

TEHRAN– Describing the reasons behind the West's double standards towards the issue of refugees and occupation, international law professor Richard Falk says the most immediate relevant answer is race, location, and control of the global humanitarian discourse.

Since the start of the Ukraine war on Feb. 24, 2022, Western countries have condemned Russia and helped the displaced by mobilizing facilities and holding various meetings, and these actions are in stark contrast to the Western approach to bloody wars and the people of the Middle East.

The double standards of the West regarding the war in Ukraine and the Middle East can be seen in the reception of refugees, reactions to the war under the titles of occupation, terrorism, defense, resistance, military aid, humanitarian aid and sanctions. Their treatment of Palestinian, Syrian, Iraqi, and Yemeni refugees and asylum seekers and other Middle Eastern countries has always been harsh and accompanied by acts of violence to repatriate them to another country or homeland.

On the other hand, the Russia-Ukraine conflict has triggered turmoil in the financial markets, and drastically increased uncertainty about the recovery of the global economy.

The Ukraine-Russia conflict had several consequences for the world economy, and since Russia is one of the countries exporting oil and gas to Europe and sanctions and tensions against Russia will continue, we have to see an increase or persistence of oil prices above $ 100 for a long time.

Meanwhile, Ukraine and Russia are global players in agri-food markets, representing 53% of global trade in sunflower oil and seeds and 27% in wheat. This rapidly evolving situation is especially alarming for developing nations. As many as 25 African countries, including many least developed countries, import more than one-third of their wheat from the two countries at war. For 15 of them, the share is over half.

According to some reports, the risk of civil unrest, food shortages and inflation-induced recessions cannot be discounted particularly given the fragile state of the global economy and the developing world due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

To know more about the issue, we reached out to Richard Anderson Falk, an American professor emeritus of international law at Princeton University and former UN official.

What is the reason behind the west's double standards towards the issue of refugees and bloodshed in different parts of the world? Why refugees from the Middle East are treated differently from the European ones?

The most immediate relevant answer is race, location, and control of the global humanitarian discourse. Europeans and North Americans more easily identify with white Christians than with dark-skinned Muslims who are generally perceived as a threat or burden. Ukraine is part of the West, indeed geographically part of Europe, and for this reason, seems natural to fall within the existential parameters of ‘the European security community.’ It seems evident that print and TV media discursively reinforce these double standards by their selective practices of coverage that mirror the impact of race and location. The obsessive daily attention given to the destruction attributable to Russian military action in Ukraine contrasts with the scant attention given to such occurrences in prior similar situations as in Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya.

Beyond these considerations, the war in Ukraine is also a crucial geopolitical battleground, pitting the U.S. against Russia, reviving the Cold War spirit of ideological confrontation although rephrased as ‘democracy’ versus ‘autocracy.’ Part of the political mix in this present setting is also China, and the evident motivation of the U.S. to warn China (by way of Russia) that if it attacks Taiwan it will face a unified national resistance reinforced by military and diplomatic support from the West that at the minimum will impose punitive, damaging sanctions. As the war drags on it has become evident that the U.S. Government cannot make up its mind whether it should solicit China as a peacemaker to end the Ukraine War or treat China as a secondary adversary, lending indirect support to Russia, and this to be confronted and even sanctioned. U.S. uncertainty at this stage may reflect a split among foreign policy advisors in Washington who favor diplomacy to end the Ukraine War and those who give priority to humiliating Russia and Putin even at the cost of extending the war indefinitely.

And also it seems there are different kinds of occupation, good occupation, and bad occupation. Why occupation of Palestinian lands is treated totally differently from the occupation of European lands?

Once more the different responses to foreign occupations reflect the tensions between the norms of international law that specify equal treatment for foreign occupations and the practices of geopolitics that allow certain states to defy this norm without suffering adverse consequences. Israel is shielded from compliance with international law because it is freed from the burdens of accountability by the geopolitical protection it receives from the U.S., often reinforced by further support received from France and the UK. Other situations that manifest similar problems are Western Sahara and Kashmir. Geopolitics is based on inconsistency arising from varying patterns of inter-governmental alignment, whereas international law is in conception independent of alignment and relative capabilities, although in practice its applicability is often subject to being subordinated to the logic of dominance, performing as a tool of geopolitical actors.

What is the main reason behind the war in Ukraine? Is it a geopolitical one? Isn't it endangering world security? Won't the west sanctions and pressures on Russia make Moscow's behavior more aggressive?

The geopolitical stakes are high. It is a two-level war, consisting of direct combat on the ground and in the air between Russia and Ukraine and a second geopolitical war between Russia and the United States over the character of world order after the Cold War. Russia is seeking to reassert a traditional sphere of influence over its ‘near abroad,’ and by doing so, challenging the American claims to be responsible for global security throughout the planet, which the U.S. has been doing since the world political system became unipolar after the collapse of the Soviet Union 30 years ago. Russia and China are trying to establish a more traditional type of geopolitical relations based on the premise of multipolarity as well as spheres of influence of the sort respected throughout the Cold War. Even during the provocative Soviet interventions in East European countries during the 1950s, the West refrained from counter-intervening, sensing that such an escalation could trigger World War III and the use of nuclear weaponry by both sides. The secondary objective of the U.S. in carrying forward the geopolitical war is to warn China not to challenge the existing situation in the South China Seas, especially bearing on the future of Taiwan.

What will be the impact of this war on the EU economy especially the economy of countries like Germany?

It is difficult to assess the economic effects of the Ukraine War. It depends on a number of imponderables—the longer the war continues, the more severe the inflationary impact on prices of food and energy, as well as causing shortages of supply; the greater the effort made by Russia to impose costs on European countries that go along with anti-Russian sanctions, the greater will be the burdens borne, especially by Germany. The U.S. does not have a sufficient capability to offset this burden by becoming an increased source of food and energy at affordable prices. It is faced with its own critical internal problems, among them a huge over-investment in unusable military assets and an inflationary spiral that is already generating political instability.

What is the impact of this war on the US economy?

It is difficult to trace causal relations, but most economists agree that rising prices of food and energy, and declining prospects of trade and investment, are having a generally harmful effect on U.S. economic conditions, especially in certain sectors, with the poor feeling most of the pain. To be sure, some private sector interests are benefitting: arms sales, gas and oil development, nuclear power, and looking to the future, construction industries and suppliers partaking

in likely massive post-conflict restorative activity in Ukraine, likely to be subsidized by generous funding from Europe, North America, and possibly Japan.

How will the result of this war affect the world order? Can it also lead to changes in the UN structure? After the Ukraine war, will the US and western powers enjoy the same influence in the world order that they enjoyed before the war?

As indicated by earlier responses, it is difficult at this stage to speculate about the effects of these two interlinked wars as they are each at midstream and relate to each other in complicated inconsistent ways. If the Ukraine-Russian War is resolved quickly it is likely to bring the world closer to the pre-1992 Cold War Era, a new phase of geopolitical confrontation and containment with the focus this time on Asia as well as Europe. If this war lingers, the world order impacts will reflect the outcome. If the Russian troops remain in East Ukraine, then the post-Cold War era will come to an end, and a new reality of bipolarity or tripolarity is likely to emerge to replace unipolarity. If Russia’s attack is reversed, sanctions maintained, and Putin replaced as leader, then the U.S. governance of unipolar world order will be confirmed for the present, although still somewhat vulnerable to Chinese economistic and regional challenges. There will be questions raised as to whether the U.S. can pay the costs of sustaining unipolarity, which requires large military investments throughout the world and in space, even if Russia’s challenge is defeated and the Putinesque scenario makes Russia again a major geopolitical actor proves to be an occasion of national humiliation.

There is also a real, yet remote, possibility that Europe might free itself from U.S. hegemony on matters of geopolitics, and come to the unexpected conclusion that NATO no longer benefits European security and that it would work out better for Europe to seek greater independence from the U.S., especially in relation to energy, economic relations, and alliance geopolitics. This would free Europe to establish win/win relations with Russia and China, as well as the U.S. If this were to happen the world might yet experience a new dawn.

In the background, are pressures to downplay confrontational geopolitics so as to achieve necessary levels of effective global problem-solving with respect to climate change, migration, and food security. Such problem-solving will require not only unprecedented levels of cooperation but also innovative arrangements that allocate financial burdens in an equitable manner, taking account of the stressed circumstances of the least developed states that are coping with the effects of global warming without either the means or a sense of national responsibility.

Relevant, also, will be the degree of enlightened, globally-oriented leadership that emerges, which could lead to a stronger UN and greater respect for international law exhibited by geopolitical actors. These goals could either be achieved by reform or self-restraint on the part of the five veto powers in the Security Council or possibly, through augmenting the authority of the General Assembly. For such constructive developments to occur there would have to be a surge of international activism reflecting a more coherent and visionary Global South. Crucial is whether the United States might reassess its global posturing and act more like a normal state, giving up both the pretensions of being the first global state and yet avoiding the temptations of reviving its historic identity as ‘isolationist’ or detached from dangerous geopolitical rivalries.