No Country for Spies - Part Two

TEHRAN – The dark side of the U.S.’s approach toward its spies is not oftentimes reflected in the mainstream media, which plays a pivotal role in keeping public opinion in the dark about what happens to people, particularly those unnaturalized, working as spies for the U.S. government.

The U.S. government has given the cold shoulder to spies who once worked for it and now experience difficulties. It exploits these personal difficulties to force them into keeping doing the same job that got them bankrupt in the first place: espionage.

It’s typical of the United States to let down those who put their lives in grave danger doing perilous jobs such as spying for it. A case in point is Nizar Zakka, a U.S. permanent resident of Lebanese descent who is running up against legal red tape on his way to naturalization.

Another case is Imaad Zuberi, an American spy who used his business cover to approach world leaders and the international business elite in a bid to spy for the U.S. After more than a decade of spying for U.S. intelligence agencies, Zuberi was sentenced in February last year to 12 years in prison for alleged offenses ranging from tax evasion to foreign-influence peddling and campaign-finance violations.

A key aspect of the Zuberi case, however, has played out in secret court filings and hearings: Zuberi was a longtime U.S. intelligence source for the U.S. government, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Xiyue Wang, a Princeton doctoral student who was convicted of espionage for the U.S. and imprisoned in Iran from 2016 to 2019, is also tasting the taste of U.S. negligence of its past spies.

He is now consumed by a legal process he initiated against Princeton University which he accused of letting him down while serving time in prison.

In the waning days of last year, Wang announced that he filed a lawsuit against Princeton for not helping him.

Perhaps, the most prominent case of a spy falling into wretchedness is Nizar Zakka who is now entangled in the never-ending paperwork required by relevant U.S. government agencies for him to get naturalized.

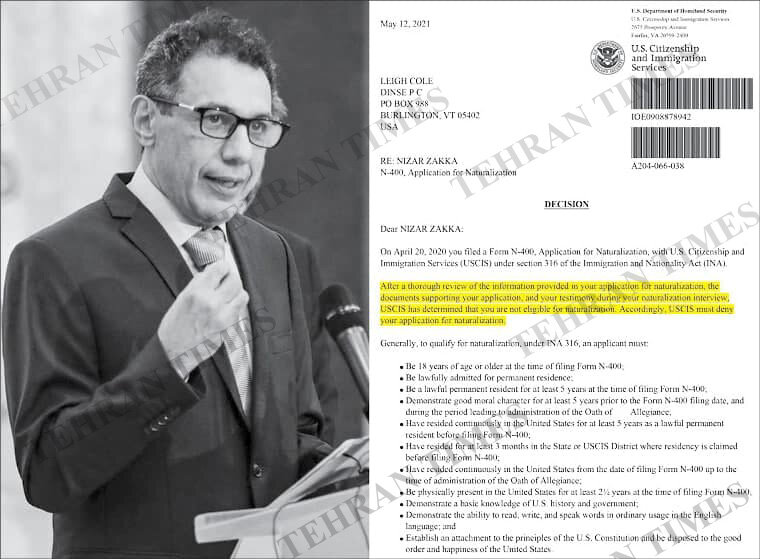

Zakka has been asking favors from various people inside and outside the Biden administration to help him with getting naturalized ever since U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) rejected his application for naturalization in May 2021, according to insiders in Washington.

On April 20, 2020, Zakka submitted an application for naturalization with the USCIS. The answer he received from the agency was so disappointing to him that he decided to reach out to some influential people in Washington, including U.S. envoy for Iran Rob Malley, to save what can be saved. As a result, he has been tackling with emotional and psychological distress after discovering the bitterness of being left to his own fate.

After reviewing the application of Zakk for naturalization, the USCIS turned down his request and denied him naturalization.

Of note, Zakka obtained permanent resident status in mid-April 2012, and in April 2020 he submitted his application to USCIS, which in turn rejected his application due to Zakka’s long-time absence from the U.S.

He was arrested in Tehran in 2015 and convicted of spying for the United States. Zakka was released from prison in June 2019. In private meetings, Zakka had repeatedly confessed that he was spying for the U.S. government. He also confessed that he was implicated in espionage schemes targeting Iranian women and girls.

The USCIS decision led Zakka to seek help from a number of influential people in Washington to help him with naturalization.

Zakka sought help from Malley, the insiders revealed to the Tehran Times, but it is not clear yet if he got any help in this regard.

The case of Zakka, as well as others, is indicative of the fact that the U.S. government's ill-treatment of its spies is not an exception, but a rule. Equally important is the duplicity with which the spies solve their problems in the U.S. While they privately admit that they were spying for the U.S. government, they keep denying their involvement in espionage on behalf of Washington publicly, a behavior that is not lost on the public.