No Country for Spies - Part One

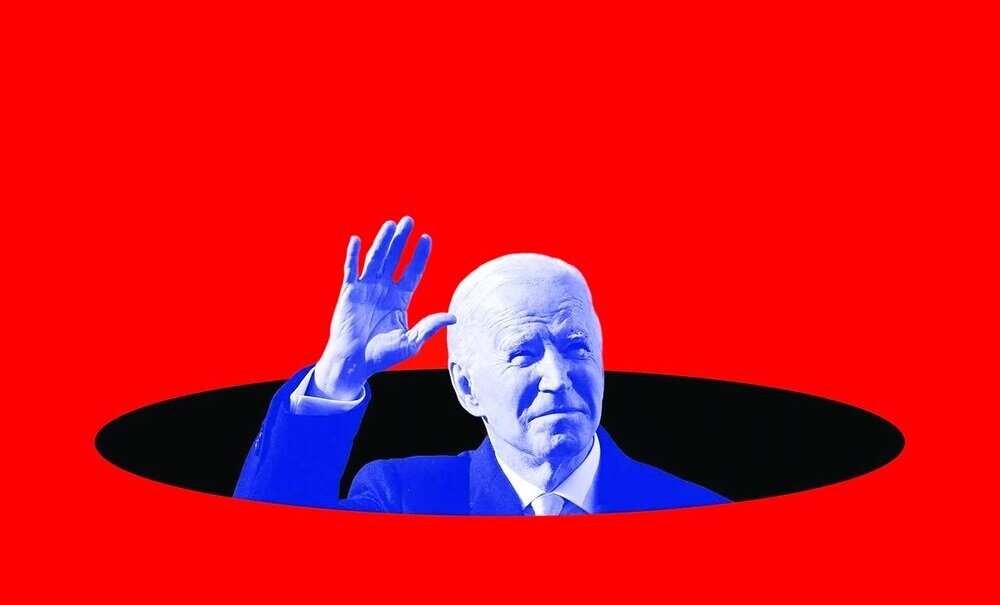

TEHRAN – The election of Joe Biden to the U.S. presidency has been depicted by many U.S. politicians and pundits as an opportunity to heal wounds left by Donald Trump. But Biden’s foreign policy, especially toward the West Asia region, proved in no uncertain terms that the U.S.’s inexorable journey toward decline continues unabated.

Over the course of his public service career, Biden fostered a self-created image of being a foreign policy savvy. One that enjoys unmatched experience and expertise in the corridors of American foreign policy.

But events ranging from Afghanistan to Yemen delivered a severe blow to his reputation. In August, the Biden administration carried out a chaotic and disorderly withdrawal from Afghanistan that led to the rise of the Taliban, the very same group the U.S. fought for two decades. The scene of Afghans clinging to and then falling from a U.S. airplane taking off from the crowded runway of Kabul’s airport caused uproar across the globe.

In a bid to whitewash his disorderly withdrawal, Biden sought to put it in the broader context of reassessing American foreign policy. “This decision about Afghanistan is not just about Afghanistan. It’s about ending an era of major military operations to remake other countries,” the U.S. president said in a speech from the White House 24 hours after the last soldier left Kabul.

Of course, the decision to withdraw from Afghanistan wasn’t Biden’s alone. It was the brainchild of the “establishment,” so to speak. But the way it was conducted reveals the extent to which American foreign policy toward the West Asia region has become messy and chaotic.

This chaos is also clear in many other hotspots. For example, Yemen is experiencing an American backing down on a Biden promise to pressure Saudi Arabia into putting an end to its war on Yemen. After some diplomatic histrionics, the Biden administration gave up on its Yemen efforts and put the blame on the Sanaa-based government for the failure of the peace talks. The Biden administration also greenlighted a Saudi escalation of bombing in Yemen. The Saudis are now operating in Yemen as if they have a carte blanche from America.

In Syria, the Biden administration shelved previous plans for withdrawal and continued to maintain its illegal occupation of Syria’s territories. In Iraq, the Biden administration insists on keeping its troops there against the will of the Iraqis.

The U.S. confused, and in some cases contradictory, policies toward the region is a sign of the U.S. decline in general. And U.S. allies in the region are already taking measures to adjust to this fact.

“America’s problems in the Middle East and its environs didn’t begin with the withdrawal. A distinct decline began 20 years earlier, with the reckless, costly and disastrous decisions to invade both Afghanistan and Iraq, followed by the decision to occupy them simultaneously and to attempt to create ‘democracies’ that would support U.S. interests,” wrote James Zogby, the president of the Arab American Institute, in an opinion piece for the UAE-owned newspaper, The National.

In many ways, U.S. allies in the region are trying to prepare themselves for post-American West Asia. A case in point is the efforts Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have done to wean themselves off defense dependence on an unreliable and increasingly unpredictable America.

U.S. intelligence agencies have assessed that Saudi Arabia is now actively manufacturing its own ballistic missiles with the help of China, CNN reported recently. Citing sources familiar with the matter, the American news television said U.S. officials at numerous agencies, including the National Security Council at the White House, have been briefed in recent months on classified intelligence revealing multiple large-scale transfers of sensitive ballistic missile technology between China and Saudi Arabia.

The UAE has also received a rebuke from the U.S. for allegedly collaborating with China in the military sphere.

The Wall Street Journal reported in November last year that U.S. intelligence agencies learned last spring that China was secretly building what they suspected was a military facility at a port in the United Arab Emirates, one of the U.S.’s closest Mideast allies.

In December, Anwar Gargash, a diplomatic adviser to the UAE leadership, said the UAE ordered work halted on the alleged Chinese facility in the country after American officials argued that Beijing intended to use the site for military purposes. But the UAE official said the facility was not intended for military uses.

“We stopped the work on the facilities,” Gargash said. “But our position remains the same, that the facilities were not military facilities.”

The cases of Abu Dhabi and Riyadh seeking secret cooperation with China have been seen by many observers as an indicator of the two Arab allies of Washington trying to reduce their reliance on Washington. Because they believe the U.S. power in the region is on the decline.

The chaotic nature of the U.S. decision-making process is not limited to its foreign policy toward West Asia. It also heavily weighs on how it deals with the spies who put their lives in danger working for Washington in potentially perilous regions.

To be continued