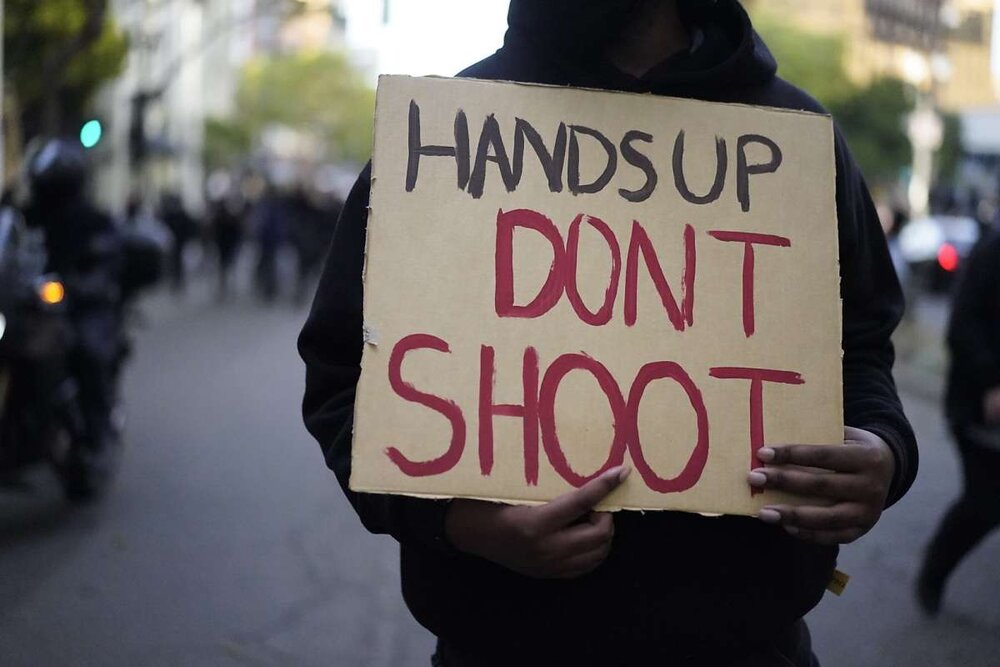

After Floyd, U.S. cops still murder and still get away with it

TEHRAN - Despite the state-to-state outcry in the United States and beyond over the daylight public execution by police of black American George Floyd in Minneapolis last year over an alleged 20-dollar counterfeit bill; a monitoring group says U.S. police are still using similar levels of lethal force and they are still not facing the consequences.

There are, in essence, three issues raised from the research that will sound the alarm among rights groups and international human rights organizations that have been very critical of American police brutality. Firstly, the astonishingly high murder rate by police, who are literally acting as the judge, the jury, and the executioner by taking the law into their own hands and using lethal force. Second is the issue of racial disparity among black and white Americans killed by police. Thirdly is the aspect of accountability, or to be more precise the lack of justice for officers who murder their victims and then walk away.

According to Mapping Police Violence, a non-profit monitoring group, American officers have killed 1,646 people, which averages to about three people every day, since the murder of Floyd in May of last year. The data will not go down well with activists and protesters who staged months of demonstrations in the aftermath of Floyd’s murder, demanding change, nor will the fact that experts believe the figure cited by the non-profit group is a conservative one. Analysts strongly believe the number of deaths as a result of excessive use of force by the police is much higher than what has been recorded or reflected in the media. For instance, campaigners have long pressed for more transparency of the federal records into how many people die when they are in police custody each year.

This is despite the monitoring group, Mapping Police Violence, using a wide variety of sources to document its data. Nevertheless, the group states on its website that “law enforcement agencies across the country have failed to provide us with even basic information about the lives they have taken. And while the Deaths in Custody Reporting Act mandates this data be reported, it is unclear whether police departments will actually comply with this mandate and, even if they do decide to report this information, it could be several years before the data is fully collected, compiled, and made public.”

Since Floyd’s public execution, very little, if anything, has changed in the United States for the plight of black Americans. Worst still for rights groups and the international community is that fatal police incidents against Americans based on the color of their skin have also remained the same as before the murder of Floyd. Despite the protests and the outcry, Mapping Police Violence has documented that black Americans are still two and a half to three times more likely than white Americans to be killed by a police officer. Experts say this issue of racism will not be easy to tackle. Speaking to U.S. media, Philip Stinson, a criminal justice professor at Bowling Green State University in Ohio thinks “many police officers exhibit a fear of Black people.” Professor Green, who tracks police criminal charges and convictions argues that “until we can address that, it is very difficult to bring about meaningful reforms.”

And to make matters worse, despite a case this year, where a jury in America has ruled against a now former police officer for killing a Black man, it represents a very tiny minority of cases in comparison with the number of murders committed by the police. While it is true that a court verdict against former cop Kimberly Potter found her guilty of two counts of manslaughter for the shooting death of Daunte Wright during a traffic stop. The high-profile case just represents an unusual decision to send a police officer to prison. Potter was the first female police officer convicted of a murder or manslaughter charge in an on-duty shooting since 2005.

It’s also just the second time this year that an officer has been convicted albeit on manslaughter charges, the other case was the conviction of Derek Chauvin for the murder of Floyd, but what about the accountability for the 1,645 other victims (an underestimated number by all accounts), who were murdered when encountering the police over the past year and a half. Criminal charges against American police remain something exceptionally rare. Activists say it underscores the power of police unions who are often found protecting officers, while legal experts say if the problem of police accountability is the law, then the American judiciary is a farce. We shouldn’t be surprised if footage showing tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of marchers rallying against police brutality against black Americans appears on our TV screens again, or more vigils being held in solidarity with families who have lost loved ones to police violence. As more awareness has been raised and little action has been taken to make changes, the eyes of the world will be zero in more and more on the killings at the hands of police officers and the reaction it triggers among the black American community and those who stand by it.

The convictions of both Chauvin, the former Minneapolis officer who was captured on an intensely painful bystander video pinning Floyd to the ground for more than nine minutes as he gasped for air and begged for his life, and Potter strike some experts as just small glimpses of a legal system in urgent need of major reform. Did the conviction of Chauvin keep other officers on their toes? All the evidence points to the contrary.

Indeed, observers are reluctant to read too much into a few isolated cases carried out under a state of media scrutiny. Paul Butler, a professor at Georgetown University Law Center and a former prosecutor says “criminal trials are not designed to be instruments of change, criminal trials are about bringing individual wrongdoers to justice. So while there have been high-profile prosecutions of police officers for killing Black people, that doesn’t in and of itself lead to the kind of systemic reform that might reduce police violence.” Other experts have argued that accountability must also be aimed at prosecutors who gave officers “carte blanche” for a century until the recent show of public outrage.

Change is not likely to come soon.

While there has been an increase from the 16 officers charged in 2020 and the highest number since some began compiling data in 2005, it remains small next to the roughly 1,100 victims killed by the police every year. There is a lot of work that still needs to be done to educate and reform the centuries old attitudes of prejudice against black Americans.

Since Floyd’s public execution, very little, if anything, has changed in the United States for the plight of black Americans. A study that has just recently been published in the peer-reviewed Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests it’s one of the largest to date on racial bias in America. Apart from finding out that black Americans are less likely to receive a response to the emails they send, the researchers say “discrimination appears to be the norm, rather than the exception.”

Critics would argue it’s safe to say white Americans enjoy a privilege in a country that self-proclaims itself as the flag bearer of democracy and beacon of human rights in the world.