U.S. Police violence on the frontline with an alarming new study

TEHRAN - In what is likely to add fuel to the fire of an ongoing debate over systemic racism in the U.S., new research reveals that more than half of police killings have not been reported in official data, and African Americans are 3.5 times more likely than white Americans be the victim.

The new figures have been published as efforts to reform policing in the wake of the murder of George Floyd collapsed after failing to win support on Capitol Hill. The new study also reports "the burden of fatal police violence is an urgent public health crisis in the U.S."

According to the peer-reviewed study by a group of more than 90 collaborators that have been published in one of the world's oldest and most prestigious medical journals, The Lancet, an estimated 55% of deaths from police violence from 1980 to 2018 were misclassified or unreported in official vital statistics.

There have been studies conducted before that have found similar underreporting rates, but the new research is one of the most significant data reviewed to date.

The Researchers compared data from the U.S. National Vital Statistics System. This inter-governmental system collects and combines all death certificates with three open-source databases on fatal police violence. These are 1. Fatal Encounters 2. The Counted and 3. Mapping Police Violence. These databases collect and document information from public record requests as well as news reports.

The study found official government data did not report an estimated 17,100 deaths from police violence out of 30,800 total deaths during the nearly 40-year period. It notes the gap between the study and the official data due to insidious intentions and a mixture of clerical errors.

During this time frame, non-Hispanic Black Americans were estimated to be 3.5 times more likely to be killed from police violence than non-Hispanic white Americans. In official government data, nearly 60% of these murders had been misclassified, which means they are not attributed to police violence.

Perhaps not surprising to some, the research indicates corruption within police departments, saying some coroners or medical examiners may feel "substantial conflicts of interest" that discourage them from pointing the finger at police officer's involvement in a death, as many work for or are embedded within police departments. Many feel "political or occupational pressure to disguise police culpability."

The researchers referred to a 2011 survey of National Association of Medical Examiners members that found 22% of respondents reported having been pressured by an elected official or appointee to "change cause or manner of death on a certificate."

Fablina Sharara, one of the lead authors and a researcher at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington School of Medicine, told American media that the U.S. National Vital Statistics System reports are often used to inform health policy. She says inaccurate data minimizes the issue of police violence and limits justice for the victims and accountability for the police.

In a press release, she also said, "recent high-profile police killings of Black people have drawn worldwide attention to this urgent public health crisis, but the magnitude of this problem can't be fully understood without reliable data... Inaccurately reporting or misclassifying these deaths further obscures the larger issue of systemic racism that is embedded in many U.S. institutions, including law enforcement."

The study found that the official government data also misclassified 50% of deaths of Hispanic people, 56% of deaths of non-Hispanic white people, and 33% of deaths of non-Hispanic people of other races. Similar to previous studies, the researchers found that non-Hispanic Black people, non-Hispanic Indigenous people were killed by police at a higher rate than other groups. Non-Hispanic Indigenous people were estimated to be 1.8 times more likely to die from police violence than non-Hispanic white people, the researchers found.

The researchers also found that from the 1980s to the 2010s, rates of police violence increased by 38% for all races.

Eve Wool is a leading author and a researcher at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. He warned the rise in the U.S. police brutality is further evidence that any steps taken to supposedly prevent police violence and address systemic racist discrimination, such as body-worn cameras and de-escalation as well as implicit bias training for officers, have "largely been ineffective."

The research found that Oklahoma, Wyoming, Alabama, Louisiana, and Nebraska are the top five states with the highest underreporting rates. The states with the highest mortality rate of police violence were Oklahoma, Washington, D.C., Arizona, Alaska, Nevada, and Wyoming.

Meanwhile, killings attributed to police violence were significantly higher for men than women, with 30,600 deaths in men and 1,420 deaths in women from 1980 to 2019.

The researchers suggested the underreporting is related to "several factors" and offered solutions for collecting more accurate data and, ultimately, eliminating police violence. However, it remains to be seen if that advice will be considered as previous similar research did not yield any tangible results. This is while lawmakers have yet to pass any significant police reforms as they continue to bicker among themselves about the problem on Capitol Hill.

About 55% of deaths from police violence were misclassified or unreported.

The study has called for Improved urgent training and more precise instructions on documenting police violence on death certificates which could improve reporting tactics. It also suggests that forensic pathologists work independently from the police and should be awarded whistleblower protection.

"Currently, the same governance responsible for this violence is also responsible for reporting on it... open-sourced data is a more reliable and comprehensive resource to help inform policies that can prevent police violence and save lives."

The research notes America's history of systemic racism and militarized police forces among the fundamental reasons for the high rates of police violence in the U.S. The study says, "to respond to this public health crisis; the U.S. must replace militarized policing with evidenced-based support for communities, prioritize the safety of the public, and value Black lives."

It highlights other nations that do not arm all police officers or only arm select officers, saying, "the difference these practices have on loss of life is staggering: no one died from police violence in Norway in 2019."

It should be noted that the study was limited in scope; for example, it did not calculate nonfatal injuries attributed to police violence, police violence in U.S. territories, or residents who military police may have harmed in the U.S. or abroad. And every state was missing some ethnic data.

Nevertheless, civil rights advocates say the findings do not come as a surprise to them. For example, Civil rights activist Toni Jaramilla tells "The police, the district attorneys, the judges are all intertwined, and they can be hesitant about reporting a death at the hands of police."

She added that "there needs to be law enforcement reform with some separation in terms of keeping police accountable, where investigators are specially assigned to investigate police misconduct."

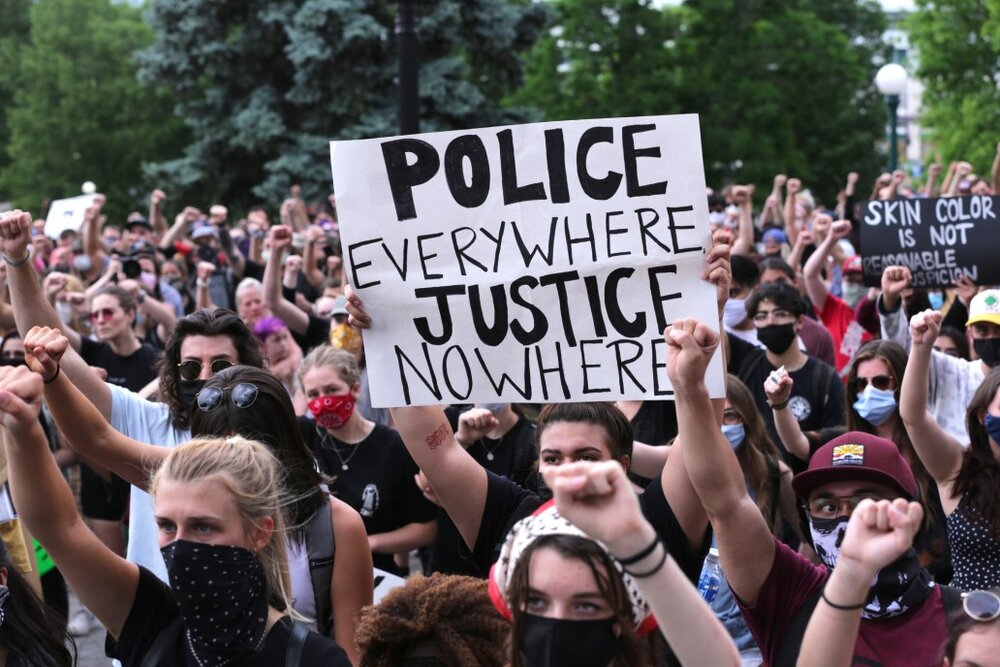

In the aftermath of the murder of black American George Floyd at the hands of a White police officer, the issue of police violence in America has been more widely documented than ever before. But the country has a long way to go before the problem of police racism disappears.