Experts necessitate elimination of all nuclear weapons

Deployment of nearly 15,000 nuclear weapons in certain countries, unreliable safety system in nuclear sites, possibility of cyber attacks on the sites and emotionally unstable rulers' threats have altogether necessitated the elimination of entire nuclear arms across the world if the humankind still intends to live on the earth, experts warned.

Sergio Duarte, a former United Nations High Representative for Disarmament Affairs, and Ira Helfand, a past president of Physicians for Social Responsibility, have expressed, in a joint article published by the Common Dreams, their concerns over the safety of nuclear power plants and sites as well as unstable rulers who posses atomic weapons.

"Just as the threat of the new coronavirus must be met by cooperation, common-sense and solidarity among peoples and nations," wrote the authors, adding the same or even more attention should be paid to narrow down the danger of a nuclear war.

The entire international community is justifiably concerned and disturbed with the serious consequences of the novel coronavirus pandemic. Thousands have already died and many more are in danger. Local and national governments find it increasingly difficult to deal adequately with the sanitary and social emergency deriving from the spread of the virus. It will take many months before the situation can come back to normal.

In the current climate of fear, uncertainty, and helplessness, it is impossible not to think about what would happen in the case of a different and more ominous disaster: a nuclear conflagration, albeit of limited proportions. The possessors of nuclear weapons are relentlessly increasing the destructive power of their arsenals and seem willing to use them as they see fit to respond to their perceived security concerns. This, in fact, brings insecurity to all. Command and control systems are not immune to cyber viruses and accidents, nor are they protected against whimsical or emotionally unstable rulers.

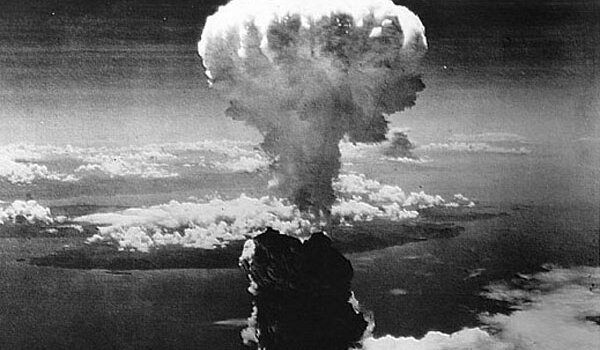

An all-out nuclear exchange would turn whole cities and vast areas into a flaming inferno. Hundreds of millions of people would perish instantly and many more would die in the following days and weeks from radiation and other harmful effects. The consequences, however, would not be confined to the immense loss of lives, destruction of buildings and transportation networks, and disruption of medical, financial, and communications systems, as well as other vital structures.

The current year will mark 75 years since the razing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with the use of just two relatively small explosive devices. Today, the detonation of a mere fraction of the nearly 15,000 nuclear weapons existing in the world would spread millions of tons of smoke, soot, and debris throughout the stratosphere and create a dense layer that would surround the planet for many years, perhaps for decades, blocking and absorbing sunlight. This so-called “nuclear winter” would cause extremely low temperatures and other climatic changes, destroying agriculture. The collapse of land and marine ecosystems would make food production impossible. Survivors of such bombings would simply starve.

Humankind cannot remain oblivious of this persisting danger to its own survival.

Three international conferences on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons, in 2013 and 2014, concluded that irrespective of its cause, the impact of nuclear detonations will not be limited to national boundaries but would cause deep, lasting and potentially irreversible harm to the environment, human health, and well-being, as well as to socio-economic development and social order, threatening the very survival of our species. Furthermore, no country, group of countries, or international organization would be able to deal adequately with the humanitarian emergency resulting from an atomic explosion in an inhabited region.

As long as nuclear weapons exist, the danger of their use will also exist. The only guarantee against such use is the complete elimination of these weapons.

In order to help avert such a disaster a comprehensive prohibition of all nuclear test explosions (CTBT) was concluded in 1996, but its full entry into force still awaits signature or ratification by eight states. More recently, in 2017, 122 countries negotiated and adopted a treaty to prohibit nuclear weapons (TPNW). 81 states already signed and 36 have ratified it. Fourteen more ratifications are necessary for it to take effect. As the current emergency inspires us to reflect more soberly about survival risks and threats, the full entry into force of these instruments looms large as urgent unfinished business.

Both those Treaties uphold and reinforce the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), usually considered the cornerstone of the nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament régime. It is fair to say that the NPT has truly contributed to limit actual and prospective proliferators to the current overall number of nine. However, the highest goal that inspires the Treaty—a world free from nuclear weapons—remains unfulfilled.

It may well be impossible to eliminate all disease-causing viruses, yet nuclear disarmament is not only possible but a legally binding obligation embedded in Article VI of the NPT. Fifty years after the Treaty’s inception, it is high time for the possessors of nuclear weapons to effectively comply with this obligation. As with viruses, containment may be good, but eradication is best.

The US atomic attack on Japan in 1945 is the blatant evidence that can simply justify the authors' concerns.

Some 140,000 people were killed in 1945 atomic bomb raid on Hiroshima, with another 74,000 bombed to death later in Nagasaki.

Some died immediately while others succumbed to injuries or radiation-related illnesses weeks, months, and years later.

Japan is the only country to have suffered atomic attacks, in 1945.

Japanese officials have criticized the UN Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty as deepening a divide between countries with and without nuclear arms.

None of the nine countries that possess nuclear weapons took part in the negotiations or vote on the treaty.

Many in Japan feel the attacks amount to war crimes and atrocities because they targeted civilians and due to the unprecedented destructive nature of the weapons.

But many Americans believe they hastened the end of a bloody conflict, and ultimately saved lives, thus justifying the bombings.

MJ