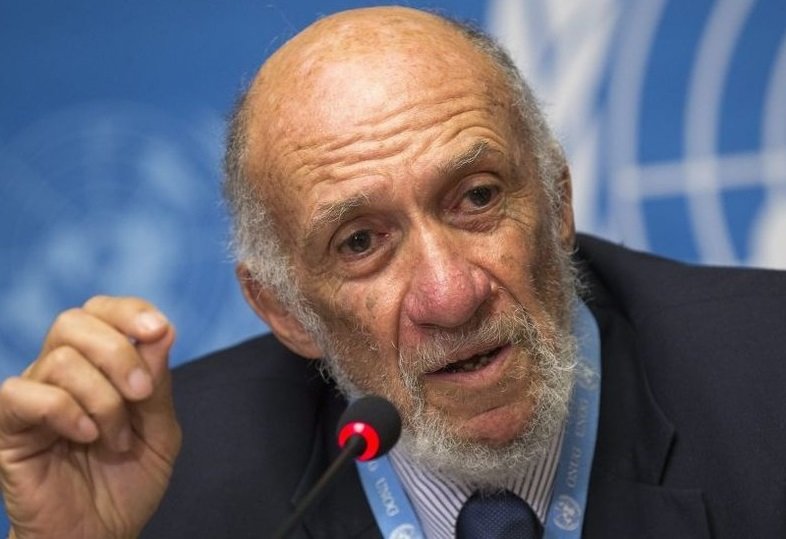

Iranian revolutionary experience had effective leadership: Falk

TEHRAN - Richard Anderson Falk, professor emeritus of international law at Princeton University, says “Iranian revolutionary experience had effective leadership and a clear vision of what it was for and against.”

Former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights says “I became rather uncomfortable after the first hour or so. I was very impressed by Ayatollah Khomeini’s demeanor, his dark bright eyes, his softly spoken confident words, and his probing questions raising serious issues.”

Following is the full text of the interview:

Q: You met with Ayatollah Khomeini shortly before the victory of the Islamic Revolution of Iran. What memory do you have of the visit? What did you think about Ayatollah Khomeini at that meeting?

A: It was a vivid climax of our visit to Iran early. Prior to the meeting we had been in Iran for two weeks. During that time, the Shah had left the country, and it became clear to the world that revolutionary movement of the Iranian people had been successful.

I remember sitting on the rug covering the ground in the tent outside his house at Neuf de Chateau. This was where Ayatollah Khomeini received foreign visitors. As I was not used to sitting on the ground for such a long time, I became rather uncomfortable after the first hour or so. I was very impressed by AK’s demeanor, his dark bright eyes, his softly spoken confident words, and his probing questions raising serious issues. In addition to myself our group consisted of Ramsey Clark, the former American Attorney General who still in close contact with many top decisionmakers in Washington and Philip Luce, a religious leader and a political activist who became known around the world when he showed some U.S. Congressmen visiting Saigon during the Vietnam War the notorious ‘tiger cages’ where political prisoners of the government were cruelly confined.

We had been invited to Iran by Mehdi Bazargan for the purpose of understanding the revolution as it really was, and not as it was being presented in distorted cartoon fashion by the mainstream Western media. While in Iran we were given the opportunity to meet a wide variety of religious leaders and societal figures who had been active in the movement against the Shah.

Q: When met with Ayatollah Khomeini, what did he think about America's relationship with Iran?

A: Ayatollah Khomeini was deeply concerned about the prospect of an American intervention. We found this concern natural and prudent. He was explicitly worried about a repeat of the experience of 1953 when Mossadegh, the democratically elected head of state in Iran, became a victim of a coup supported and encouraged by the CIA, and designed to restore imperial dynasty of Reza Shah Pahlevi. Ayatollah Khomeini sought our opinion as to whether the U.S. Government would organize some kind of counterrevolutionary response designed to restore the power and authority of the Shah’s regime. We responded that such a risk existed, but we were not in a position to assess its seriousness.

If no coup or counterrevolutionary moves was attempted, it was our impression that Ayatollah Khomeini seemed open to normal relations with the West. If there was American interference in internal Iranian affairs relations would be strained. The new leadership in Iran would use all means at its disposal to resist any attempt to intervene. If Washington was prepared to accept the reality of the new Islamic Republic of Iran, Ayatollah was ready to endorse normal diplomatic relations, and even spoke of a willingness to maintain earlier commitments to purchase American military equipment.

Q: You were accompanied by an American delegation to travel to Iran. That American delegation opposed U.S. involvement in Iran's internal affairs, and that meeting was initiated by the Prime Minister's invitation of Bazargan. During that trip, you talked with the last prime minister of the shah, Shapur Bakhtiar and the last American ambassador to Iran, William H. Sullivan. At that time, what did they comment on the Events and Developments in Iran? Did they think that revolution would occur in Iran?

A: As your question suggests, we were more clearly opposed to past and any future U.S. intervention in Iran than we were supporters of the revolution. We came to Iran hoping to learn about what was happening, and what to expect from the new leadership. We tried our best to meet a wide range of relevant personalities who were in one way or another involved with these dramatic developments. We did not receive clear or consistent answers to our questions about what to expect in post-Shah Iran, and were told on more than one occasion that ‘the revolution happened too quickly,’ in the sense that there was no time to prepare for the future.

Our meeting with Prime Minister Shapur Bakhtiar occurred on the evening that the Shah left Iran. Bakhtiar seemed nervous and somewhat agitated. He was surrounded in his office by a group of men whom we assumed were associated with Iranian intelligence, and likely not sympathetic with this remnant of the former government. Bakhtiar acted as if he was almost a prisoner despite the fact that he was still holding the highest office in the government. When we asked to visit the political and ordinary prisoners on the following day, Bakhtiar turned to these minders in the room before responding. He told us we had permission to visit the political prisoners, who were soon to be released, but not the common criminals, presumably because the conditions of their confinement was far below international standards.

Overall, Bakhtiar gave an impression of being an unhappy casualty of history, not questioning the revolutionary results directly, yet not being able to reconcile his secular outlook with the prospect of a religious oriented political leadership, and undoubtedly very worried about his own fate. In some senses, Bakhtiar conveyed an impression of a European style of worldliness, including an obvious affection for French culture.

Our meeting with the American ambassador, William Sullivan, was problematic for a number of reasons. Clark had little respect for the kind of diplomacy that Sullivan practiced while serving as ambassador in Laos, which included authorizing the use of the embassy to coordinate military attacks on the Laotian countryside as an extension of the then ongoing war in Vietnam. Sullivan had the reputation of being a counterinsurgency diplomat. Clark was initially opposed even to our seeking a meeting with Sullivan, but I persuaded him that the credibility of our impressions of Iran would be increased if we heard what he had to say. Meeting with Sullivan was also problematic for me as I had testified a year or so earlier in the U.S. Senate against his appointment as ambassador to Iran, alleging that he was guilty of war crimes in Laos.

When we entered Sullivan’s spacious office, I was greeted with these words, “I know Professor Falk thinks I am a war criminal.” I didn’t nothing to alter this perception, remaining silent. Sullivan didn’t express any hostile feeling toward Ramsey Clark. After this initial tense moment, Sullivan gave us a clear briefing about what was happening in Iran, emphasizing his difficulties with respect to persuading the White House to accept the outcome of the revolution. Sullivan made clear to us that he was very unhappy with the role being played by Zbigniew Brzezinski, the National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter, who refused to accept the unfolding realities, and remained intent on reversing the revolutionary outcome, and tried in various ways to promote a result that Sullivan opposed as unwise, and likely counterproductive. I later wrote and spoke about this meeting in ways that reported these views, and turned out to be damaging to Sullivan’s career after it was determined via Clark that our meeting was on the record, that is, it was thus permissible to repeat to the media what we had been told in Tehran. In fact, we had the impression that Sullivan was so upset by Brzezinski’s behavior that he wished that his efforts to turn the clock back in Iran be made public.

I recall an incident during ‘the hostage crisis’ that occurred some months later when I had been asked to act as an intermediary between Iran and the U.S. because there was no direct contact between the two countries. It was at a time fairly early in the crisis when Ayatollah Khomeini let it be known that he would look with favor if an African American diplomat had been sent to negotiate the release of the hostages. Andrew Young, who satisfied the ethnic criterion set by the Iranian leader had been suggested as the appropriate person to carry out such a mission, and I had agreed to accompany him as a kind of resource person. Young was ready and willing, but he didn’t want to burn his bridges in the U.S., and insisted as a precondition on a green light from the White House. When this was refused, and Young declined, the furious head of the Iran Desk in the State Department who was eager to defuse the crisis, told me “Brzezinski would rather see the hostages dead that see Young get credit for their release.”

Among the other valuable aspects of this meeting with Sullivan was his acknowledgement that before the revolution the American Embassy had prepared 26 scenarios of what could go wrong in Iran from the perspective of the stability of the Shah’s governance, and not one of them had perceived a threat from Islamic sources. The Cold War mentality had focused on various threats from Marxist and Soviet sources, but the Islamic dimension was assumed to have been either subordinated, or at least neutralized, by the exile of Ayatollah Khomeini or aligned with the anti-Marxism of the Shah.

Q: When you were in Iran, the Shah left Iran. What is your memories of those days and those events?

A: I remember that day very clearly. We had gone to the city of Gazvin to meet at the home of some doctors who had treated Iranians wounded in anti-Shah demonstrations. They had told us about the Iranian armed forces entering the hospitals, and removing some of those wounded and generally interfering with humane and effective medical attention given to these nonviolent participants in political activities hostile to the government.

While having lunch, the radio reported the Shah’s departure but some of the Iranians present were stunned, and wondered whether the reports were even true. I remember a doctor worrying that this might be a trap designed to lure anti-Shah militants to engage in victory demonstrations that would be crushed by a military crackdown. As the news sank in, and was accepted as accurate, concerns gave way to a celebratory mood. On the drive back to Tehran to keep our appointment with Bakhtiar, the road became more crowded with cars blowing their horns and displaying flags and posters of Ayatollah Khomeini. It was a scene of intense political excitement.

On the following day we walked in a huge demonstration affirming the Shah’s departure and the prospect of transformative change in Iran, the nature of which was not yet clear. It was a moment of popular excitement and hopefulness, and an impressive celebration of the unity that joined many elements in the extraordinary struggle against the Shah that had been viewed skeptically until this moment when its success could no longer be doubted.

It was sad to witness during the days that followed the beginnings of disunity among these forces that had so recently joined together against the Shah. The main early tension involved women who were fearful that their progress in secular Iran would not be sustained if the governing process took a religious turn. Also, it became evident to me that the left component of the anti-Shah movement would not accept the dominant religious tendency, and vice versa.

Q: Previously, you said that when you referred to the revolution of Iran in a meeting with Ayatollah Khomeini, Ayatollah Khomeini corrected your remarks and he said the “Islamic” Revolution of Iran. Is it possible to explain more about this? Why did Ayatollah Khomeini emphasize Iran's Islamic Revolution rather than the Iranian revolution?

A: It was only somewhat later that I began to understand why Ayatollah Khomeini gave such importance to this matter of naming of the revolution. By calling the post-Shah Iran the ‘Islamic Republic of Iran’ there were several ideas present. First of all, was the point that Iran was an Islamic society, and to say this was to express the basic character of the political community of the country. To be ‘Islamic’ was also to be part of a larger religious and civilizational community than could encompassed be a territorial sovereign state, and could be interpreted as the basis of an Islamically oriented political challenge to the secular governments in Islamic majority countries. During our meeting, Ayatollah Khomeini also expressed his strong belief that ‘peace diplomacy’ after World War I had wrongly imposed the European concept of territorial state on the region with its emphasis on ‘national’ identity that displaced religious and cultural identities alone capable of establishing a voluntary community.

Further the idea of an ‘Islamic Republic’ drew a sharp contrast with the idea of a secular, dictatorial monarchy, with dynastic claims to exercise leadership, that had characterized the imperial governance of the Pahlavi Dynasty. Present also was the notion of ‘republic’ that seemed to signal an intention to establish limits on governmental authority and to protect the citizenry against abuses of state power, preferably under the guardianship of religiously respected figures.

Ayatollah Khomeini also made clear his view that monarchy and dynastic rule lacked political legitimacy. He referred explicitly to Saudi Arabia, insisting that it was no more legitimate than had been the Shah’s governance structure.

Q: You talked to a lot of American officials on that days (Days before Iran revolution). In your opinion, why did American officials never support the Iranian revolution and government?

A: The U.S. relationship with Iran was dominated by ideological and geopolitical considerations ever since the Shah was returned to power, with Washington’s help in 1953. The Shah was a compliant partner with the United States during the Cold War, serving as the anchor of the containment policy directed at the Soviet Union, an important customer of the American arms industry, and a willing participant in the liberal world order serving private corporate and financial interests. Beyond this Iran was willing to be an oil supplier to both Israel and South Africa at a time when the U.S. was eager not to be seen as defying world public opposition by befriending these two governments. Against this background, it is not surprising that Henry Kissinger called Iran ‘the rarest of things, an unconditional ally’ in his political memoir.

At the same time, there was a suspicion about what the revolution portended, even the fear that it would push Iran into the arms of the Soviet Union, and represent a major setback for the U.S. in the ongoing Cold War rivalry. The populist character of the revolution was also perceived as a threat to Israel, especially given the outreach of Ayatollah Khomeini to the entire Islamic community and his clear rejection of Zionist claims to govern Palestine, including Jerusalem. In our meeting Ayatollah Khomeini made a clear distinction between the Jewish religion that he called ‘an authentic religion’ and Zionism that he regarded as a political project hostile to the Palestinian people and to Islmaic interests and values. He also distinguished between Jews, whom had historic roots in Iran and he hoped would remain after the revolution, and Bahais, whom he categorized as ‘a sect’ that had no legitimate place in the Islamic Republic he envisioned.

Q: Previously you described Ayatollah Khomeini as a true and genuine revolutionary. In your opinion, what was the difference between the Iranian revolution and the developments of the Arab Spring in 2011? Was the Egyptian Revolution in 2011 a genuine and real revolution?

A: I think this is a really important question. The main difference is that the Iranian revolutionary experience had effective leadership and a clear vision of what it was for and against. It also understood in ways that were not present during the Arab Spring, especially as developments unfolded in Egypt, that the Iranian revolutionary process was threatened from without and within. Perhaps, Ayatollah Khomeini and others in the leadership were taking prudent account of their memories of the 1953 coup, and their realization that this could happen again in Iran if serious precautions were not taken. Arguably, such a learning of the ‘Lessons of 1953’ produced some repressive over-reactions, using the fears of counterrevolution to justify actions taken against internal liberal adversaries and other perceived ‘enemies.’ Such an assessment remains to be made, requiring some inside knowledge that I do not possess.

The Arab Spring political movements were unstructured, seeking to challenge the established order, but without any clear agreement on ‘what next.’ This fluidity created ample opportunities for external and internal elements opposed to transformation to reassert themselves after the dramatic moment had passed when the hated leader had been overthrown. Perhaps, also, the political inexperience of the Muslim Brotherhood also accentuated the vulnerability of these movements to reversals in the public spaces of several Arabic countries after displaced elites had regrouped to stage a comeback.