An ailing French Republic totters towards meltdown

The outworn political order may be on the brink of a complete overhaul

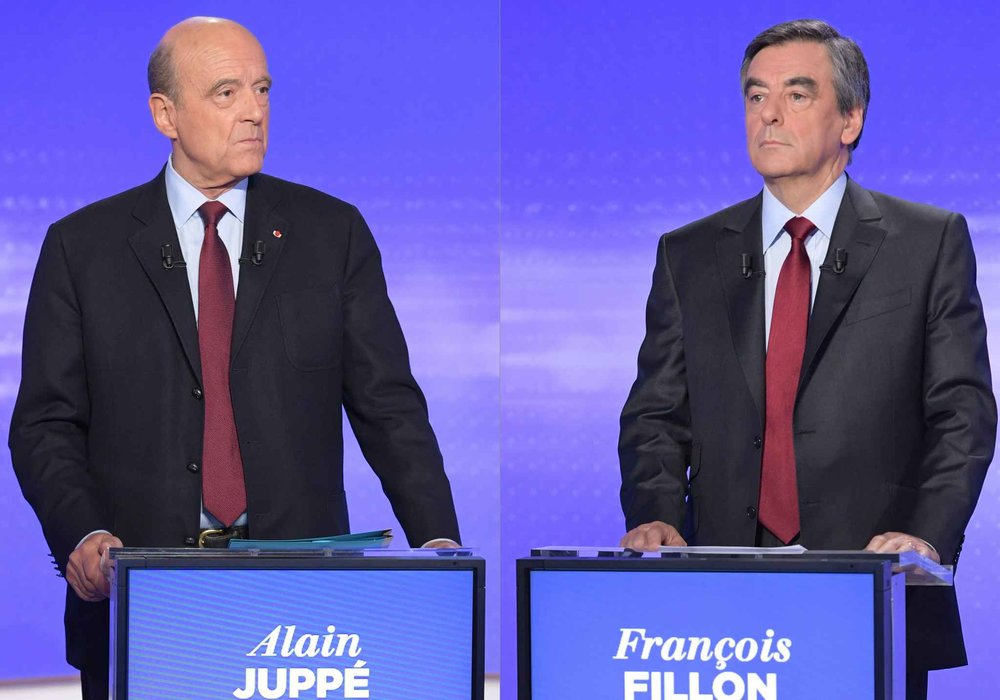

France has reason to thank Alain Juppé. The Bordeaux mayor and former prime minister this week wisely declined to offer himself as a replacement for François Fillon, the Center-right presidential contender whose campaign is drowning in allegations of financial dishonesty.

As Juppé recognizes, he lost his party’s primaries fairly and squarely to Fillon in November, and he is not the man to revive the center-right’s receding prospects of victory in May. But the nation is in debt to Juppé for another reason. In his speech in Bordeaux, he delivered the campaign’s most eloquent summary of why this year’s presidential and parliamentary elections are France’s most important since Charles de Gaulle set up the Fifth Republic in 1958, during a similar phase of high national drama. “Our country is ill. Resistant to reforms that it knows are necessary, angry with its political elites but susceptible to demagogic promises, it is experiencing today a terrible crisis of confidence,” Juppé said. Most candidates, from extreme left to center and far right, have pronounced the French political system to be in deep trouble. But none has diagnosed its sickness as pithily as did Juppé. As he bowed out of the election race once and for all, nothing became him in his campaign like the way he left it. Despite his talents, two aspects of Juppé’s long career illustrate why the political order is outworn and may be on the brink of a complete overhaul. De Gaulle depicted France’s history as oscillating between moments of grandeur, when the state is strong and the nation is united, and the immense sorrows of a disorganized people. Juppé knows all about the sorrows.

Despite his talents, two aspects of Juppé’s long career illustrate why the political order is outworn and may be on the brink of a complete overhaul.In November 1995, he tried as premier to reform France’s lavishly funded welfare state. A strike wave erupted, the biggest since the événements of 1968. That was more or less the last time any French government attempted serious economic reform. Much milder changes under François Hollande’s presidency sparked furious protests. As Juppé indicated in Bordeaux, many French people grasp the need for reform. But the political classes are divided and their fear of the street is palpable.

Illegal party funding

The icy hand of immobilism holds the Fifth Republic in its grip. The second relevant episode of Juppé’s career is his 2004 conviction for illegal party funding, an offence for which he received a 14-month suspended prison term.

inancial scams like this are as essential an ingredient of modern French politics as fish stock in bouillabaisse soup. The worst example in the Hollande presidency concerns Jérôme Cahuzac, the disgraced former budget minister responsible for fighting tax evasion, who concealed €600,000 in secret accounts in Switzerland and Singapore. Voters resented the shameless behavior of the political elites long before Le Canard Enchaîné, a satirical weekly, blew open the election campaign by alleging that Fillon had used public money to pay his wife and children for fictitious work. The allegations were devastating because Fillon had solemnly presented himself as a whiter than white, reform-minded candidate. He denies all wrongdoing, but says he expects that magistrates will summon him on Wednesday and may place him under formal investigation. The Fillon affair is plunging France’s center-right Republicans party into disarray. Its candidate horrifies aides and supporters with snarling, Silvio Berlusconi-style talk of his “political assassination” by enemies in the judiciary and media. Yet the ruling Socialist party is in no better state. The party, demoralized by Hollande’s ineptitude and lurch from half-baked leftism to undercooked market reform, chose Benoît Hamon as its candidate, a radical with no more chance of victory than Bernie Sanders in the 2016 U.S. presidential race.

Here is damning evidence of systemic meltdown. For the first time, it is conceivable that neither of the two parties that epitomize Fifth Republic politics will be in the presidential election’s second, knockout round. This would damage their prospects in the June parliamentary elections, too. In such a rollercoaster campaign, it is premature to conclude that the run-off will definitely pit Emmanuel Macron, an independent centrist, against Marine Le Pen of the far-right National Front, and that Macron would be the certain winner of such a contest. Imagine, however, that Macron becomes president and En Marche!, his new party, wins a good share of parliamentary seats. How easy would it be for Macron to fashion a new political order on top of the ruins of the old? Having written his master’s thesis on Machiavelli, Macron will remember the Renaissance philosopher’s warning in Chapter VI of The Prince: “We must bear in mind that nothing is more difficult to set up, more likely to fail and more dangerous to conduct than a new system of government; because the bringer of the new system will make enemies of everyone who did well under the old system, while those who do well under the new system still won’t support it warmly.”

(Source: FT)